The Sabbath appears out of place in the Ten Commandments. It is the only ritual requirement in the bunch. Tucked in between the first three commandments, which deal with monotheism and idolatry, and the following six, which regulate relations between people, is connected to both categories yet fully part of neither.

It is among the best known Jewish practices, and one of the least understood.

We are commanded to rest, yet nowhere is the meaning of rest spelled out in the written Torah. The rabbis, on the other hand, provide us with more details than we might care for. It becomes a violation to pick a flower, write a poem or, later on, flick a switch.

“Are we dealing here with extravagant and compulsive exaggerations of an originally `sensible’ ritual,” psychoanalyst Erich Fromm wrote, “or is our understanding of the ritual perhaps faulty and in need of revision?” Fromm’s answer was the latter, and he provided the following definition of what is forbidden on the seventh day: “‘Work’ is any interference by man, be it constructive or destructive, with the physical world. Rest is a state of peace between man and nature.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

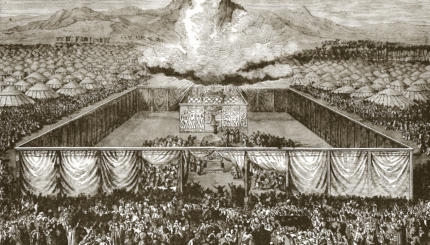

This aggadah of Shabbat, the theory behind the practice, is hinted at in the commandment itself: We rest in imitation of the original divine rest that was the climax and cessation of Creation. Yet God’s rest allowed the world to exist without divine intervention. In the same way, Shabbat is as much a respite for the world as it is for the people who observe it. How else can we understand a day of joy and rest that prohibits labor-saving devices, and involves frequent inconvenience – but by seeing that something other than human needs are paramount?

Creation and Rest

The link between the commandment and the creation story indicates how Shabbat rest contrasts with creative labor. Genesis describes a very anthropocentric world: Humanity stands at the head of the created beings, as benevolent dictator in chapter 1, and conscientious steward in chapter 2. Shabbat implies an approach that can be labeled biocentric, demanding that humans abstain from domination. It thereby allows them to see themselves as creatures, rather than creators.

Orthodox philosopher David Hartman says of the seventh day: “… the flowers of the field stand over and against man as equal members of the universe. I am forbidden to pluck the flower or to do with it as I please; at sunset the flower becomes a `thou’ to me with a right to existence regardless of its possible value for me… The Sabbath aims at healing the human grandiosity of technological society.”

Shabbat, then, is to time what a nature preserve is to space. Both are “places” marked with distinct boundaries. In both, the soul of the human “visitor” is refreshed, while the natural order is preserved in its unviolated form. Outside the boundaries, we do not seek to negate civilization, the realm of human action, and make the whole world a preserve. But ideally the values experienced inside the “fence” will influence how we view the world beyond, and our role in it.

But there is an unresolved tension between the lofty aggadah and the nitty-gritty of the Shabbat halakhah. If Shabbat implies renouncing human domination over the natural world, and represents a more harmonious relationship with the rest of creation, then how can we justify the waste involved in modern observance of the Sabbath, such as leaving lights and other electric appliances on for the entirety of the day? And doesn’t Sabbath observance become a violation of the of bal tash’hit – the prohibition of senseless waste? Some observant Jews look to technology to solve the problem: Let timers operate our lights; let us “observe” the Sabbath by using electronic relays and devices invented specifically for the seventh day.

But is turning to technological innovations to comply with restrictions in the Sabbath’s spirit of humility and human creatureliness? Rather, it only emphasizes our continued scientific exploitation of nature, and the use of the uniquely human creative impulse that we are meant to be restraining on this day. Perhaps there is no single solution that will satisfy all Jews, but I believe that the issue must be addressed when teaching, and observing, Shabbat.

Excerpted from The Jerusalem Report, January 26, 1995.