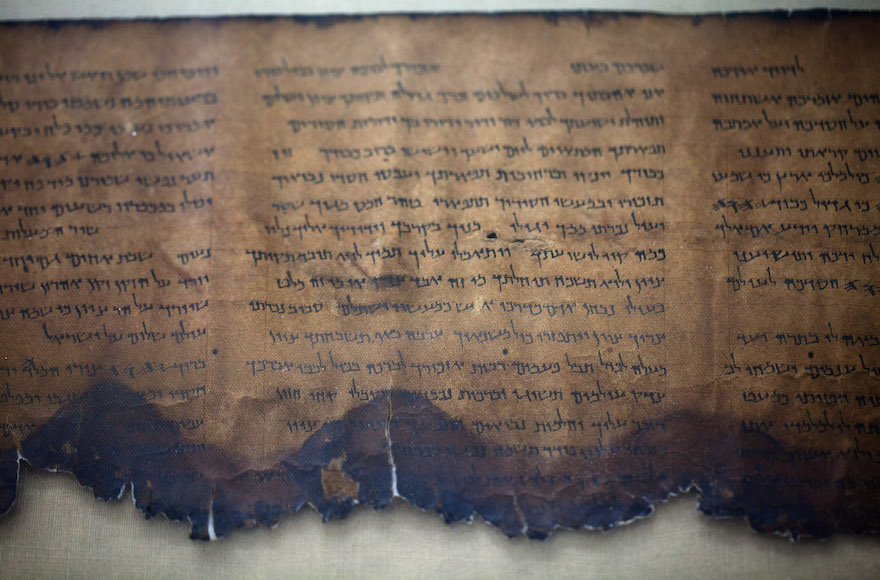

The Dead Sea Scrolls are the most prominent historical record of Jewish life in the Second Temple period. In the past century, scholars pieced together more than 900 documents that comprise this collection–mostly in Hebrew with a few in Aramaic and Greek–and concluded that they belonged to an ancient Jewish sect.

Because this library was discovered in the Judean desert in Israel, most scholars believe that the sect lived in this area. Communal halls and buildings have also been discovered close to the caves where the scrolls were found. Scholars believe the sectarian community hid the documents in nearby caves, fearing the Roman invasion of Palestine in 68 CE.

The Discovery of the Scrolls

In 1947 the first jars containing what is known today as the Dead Sea Scrolls were accidentally discovered by a young Bedouin shepherd near the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, in Wadi Qumran, present day Israel. One of the most important finds within the Scrolls are the oldest known records of the Hebrew Bible, dating back to the second century BCE. Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha texts were also found within the Qumran library. Altogether, the 900 documents that were found in and around Qumran include legislative material, commentaries and embellishment on the Pentateuch, and hymns that scholars believe were recited by the Qumran community on special occasions.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have added a major chapter to Jewish history by giving scholars a better understanding of the Jewish community during the Second Temple period. The texts seem to have been produced by a sectarian community that was apocalyptic in nature, expecting a battle between good and evil in the near future. This community embraced a distinctive, older calendar that differed from the calendar used by the Jerusalem community. Based on this, scholars believe the Qumran sect fled to the Judean wilderness due to a schism with the mainstream Jewish community, probably related to priestly practices and authority in the Temple.

Biblical Texts

Scrolls and fragments of scrolls from all books of the Hebrew Bible have been discovered at Qumran, with the exception of Esther and Ezra/Nehemiah. The best preserved document is the Great Isaiah Scroll, which includes all 66 chapters roughly intact. Two full Isaiah scrolls were discovered at Qumran along with fragments from at least twenty additional Isaiah scrolls. Scholars believe the book of Isaiah was one of the more revered writings of this sectarian community, which might have believed it was fulfilling the words of the prophet: “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord (Isaiah 40:3).”

The text of the Qumran Isaiah scrolls sometimes differs from the Isaiah text in today’s Hebrew Bible. Scholars believe that when the Dead Sea Scrolls were composed, only the Pentateuch was considered canonical. All supplementary books, including those found in Prophets and Writings, were considered complementary to the fixed Bible text–and multiple versions of these books existed.

Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

A number of Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha documents were also discovered at Qumran. Although not preserved by later Jewish communities, these texts were sustained by different branches of Christianity. The two most prevalent in the Qumran library were the books of Jubilees and Enoch, which both have been preserved in the Ethiopian Orthodox canon.

Jubilees is a text that deals mainly with adjusting the calendar to biblical events from the beginning of Creation. Its prominence among the Dead Sea Scrolls suggests the meticulous nature of the Qumran sect Enoch predicts an assortment of apocalypses. Its prominence is consistent with the messianic mentality of the community.

Two texts preserved from the Apocrypha are the books of Tobitand Sirach, also known as the Deuterocanonical books, preserved in the Roman Catholic canon. Their discovery among the Dead Seas Scrolls is evidence of the Jewish origin of these texts.

Legislative Documents

Perhaps the most interesting content found in the Dead Sea Scrolls are texts unique to the Qumran community. These fall into three categories: legislative documents, hymns, and biblical embellishments.

The legislative documents from Qumran indicate the community was strict and particular in its performance of biblical laws, and also implemented its own, non-biblical regulations. The Manual of Discipline identifies distinct practices of the group, while the Damascus Document condemns the ritual practices of the sect’s opponents in Jerusalem.

The apocalyptic nature of the community comes out in the War Scroll, which discusses a battle between the Qumran sect, “the Sons of Light,” and “the Sons of Darkness” and presents instructions for an expected 40-year war.

The Temple Scroll adds to and revises the laws of Deuteronomy and the description of the Temple in Jerusalem. Another document, named by scholars 4QDeuteronomy, combines passages of Deuteronomy and Exodus to explain observance of the Sabbath. Other issues in these legislative documents include membership in the community and punishments for offenses committed at Qumran.

Hymns and Biblical Additions

The hymns found in the Dead Sea Scrolls feature psalms and blessings probably recited by the community on special days. The Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice describes classes of angels and their heavenly worship service on 13 consecutive Sabbaths, covering one quarter of the year. This document highlights the solar calendar used by the Qumran community. As seen with Jubilees and Enoch, calendar and time were fundamental issues for the sect. A text identical to Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice was also discovered at Masada in 1965, suggesting the hymn traveled with those who took refuge at Masada when fleeing from the Roman invasion in the first century CE.

Another document, Thanksgiving Psalms, or Hodayot, has roughly 25 hymns each beginning with “odekha adonai” (thank you my Lord). Scholars believe these hymns were the community’s prayers and songs of praise appointed to certain days and time of the week. According to Qumran prayer scholar Esther Chazon, the authors of some of the Hodayot even claimed to be among the angels themselves and included prayers like the Kedushah, which echoes biblical narratives of angels’ worship.

Biblical embellishments took on two forms at Qumran. Those in pseudepigraphical style claimed to be authored by biblical characters. Genesis Apocryphon, for example, is told from the perspective of Lamech, Noah’s father. It retells the stories of Noah and Abraham with enhanced details, and like Enoch was written in Aramaic. The Qumran copy is the only version of this text that has been found.

Pesharim were another sort of biblical addition unknown until discovered at Qumran. In this genre, texts from the book of Prophets are rewritten and each verse is followed by an interpretation relating to the day and age of the Qumran community. For example a pesher relates Habbakuk’s “arrogant man” (Habbakuk 2:5) to an contemporary adversary: the Romans (Kittim).

The Community at Qumran

When the Dead Sea Scrolls were first discovered, most scholars believed the Qumran community was connected to the Essenes, a group described by first century writers Josephus, Philo, and Pliny the Elder. As Josephus describes in Wars, the Essenes were religious, communal, ascetic, celibate, and held apocalyptic beliefs. This seemed to resemble to Qumran community.

Today, after the publication of all 930 scrolls, scholars no longer believe the Qumran sect was the same group described by Josephus. The scrolls use terms like “female elders,” “mothers,” “sisters” and “daughters”–but there were no women leaders in Essene communities.

Furthermore, the term “Essene,” is never mentioned in the scrolls, and instead the group refers to itself as the Yachad or B’nei Zadok. The former term was probably a name used for the entire congregation whereas the latter expression was specific for the governing group of the sect, namely the priests.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, the earliest Jewish documents we have today, confirm to historians the longevity of the Jewish religion. But they also attest to the array of sacred texts within the ancient Jewish world before rabbinic canonization. Studies in the scrolls are still at a very young stage.

In 2004 two fragments of Leviticus 23 and 24 were discovered at Qumran. More recently, in September 2007, a tunnel leading from Jerusalem to the area of Qumran was found, suggesting that some of the scrolls and other treasures from the Temple were brought to the area to hide from Roman destruction. Radiocarbon dating and DNA testing are being used to find a more exact date for the scrolls. Today, the scrolls reside in the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem’s Israel Museum.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.