Commentary on Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9

On the surface, capital punishment looks like a perfect embodiment of justice. What could be a more fair and logical consequence for people who take others’ lives? The seems to unequivocally support the death penalty. Deuteronomy teaches, “Life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot (Deuteronomy 19:21).” Moreover, numerous biblical offenses are punishable by death, murder being only one of them.

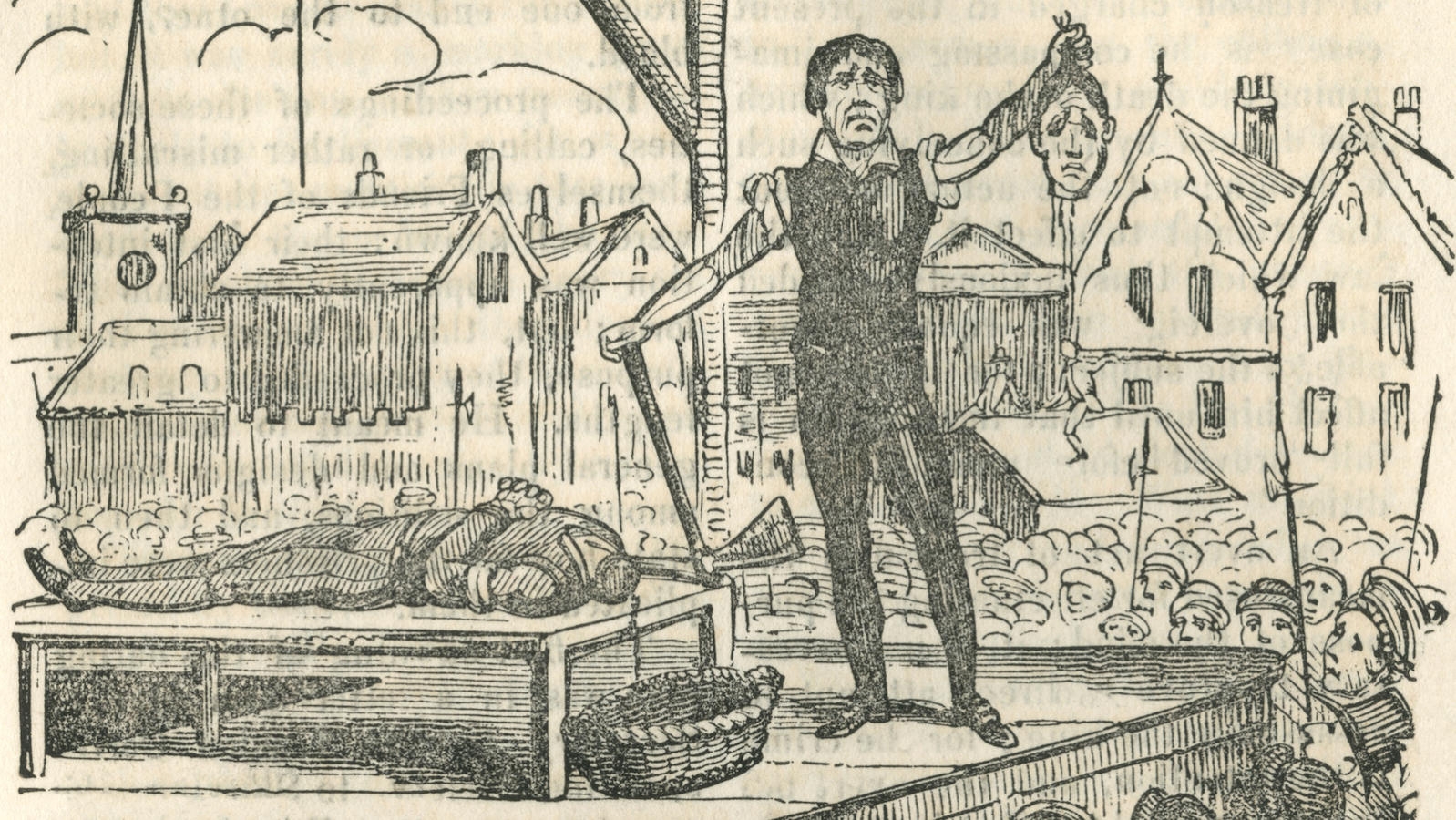

Parashat Shoftim, however, reflects a more complex perspective. Although our Torah portion affirms the use of capital punishment, a deep ambivalence surfaces in the description of biblical executions: “Let the hands of the witnesses be the first against him to put him to death, and the hands of the rest of the nation thereafter (Deut. 17:7).”

The requirement that the witnesses, whose testimony condemned the criminal to death, throw the first stones, forces them to consider whether they are prepared to bear the responsibility of extinguishing a life. And the community’s participation ensures that all Israelites share this responsibility. Blood shall be on everyone’s hands; no one may grow numb to capital punishment.

This ambivalence deepens in the Talmud. The rabbis effectively abolish capital punishment, primarily on the grounds that human justice systems are fallible and that executing wrongly convicted individuals is unacceptable. The death penalty should be left in the hands of God, so to speak. (Sanhedrin 37a-b, Ketubot 30a-b)

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Rabbinic Hesitation

To ensure this, the rabbis prescribe extremely stringent legal measures for capital cases. For example, witnesses must have seen the entire crime as it was being committed, circumstantial evidence is illegitimate, and the accused receives the benefit of the doubt. It is virtually impossible to sentence someone to death in rabbinic courts. Thus, the (Makkot 7a) teaches:

A Sanhedrin [rabbinic court] that executes once in seven years is destructive. Rabbi Eliezer ben Azariah says, ‘Every 70 years.’ Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva say, “If we were in a Sanhedrin, no man would ever be executed.

Centuries later, Maimonides proclaims (Sefer Hamitzvot, negative commandment no. 290), “It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death.” Considering the inevitable margin of error in any justice system, Maimonides essentially eliminates the death penalty.

In the spirit of the rabbinic limitations on capital punishment, more than two-thirds of the countries in the world today have abolished the death penalty. But dozens have not. Last year, at least 8,864 people were sentenced to death in 52 countries and at least 2,390 people were executed in 25 countries.

Contemporary Concerns

Rabbinic fears about misapplication of the death penalty are being realized today as governments execute numerous people every year without fair trials. In Nigeria, hundreds who currently sit on death row did not have fair trials and around 80 have been denied the right to an appeal. India has been notoriously arbitrary and inconsistent with its death penalty cases in investigation, trial, sentencing, and appeal stages.

No court system in the world transcends human fallibility, even our own. The U.S. has released 120 death row inmates on grounds of innocence since 1975, leaving to our imagination how many innocent Americans have been erroneously executed.

Moreover, capital punishment is often fraught with discrimination against marginalized populations. Nearly half of those executed last year in Saudi Arabia were foreign nationals from the Global South, many of whom lacked defense lawyers and could not follow their court proceedings in Arabic. The death penalty is also sometimes used to silence political opposition. In Chad, a judge sentenced the former president and 11 opposition leaders to death in order to preserve “constitutional order, territorial integrity and security.”

Because human justice systems are, at best, imperfect, death sentences do not belong in our courtrooms. We should support the international movement to abolish the death penalty, beginning by protesting capital punishment in the U.S, which in 2008, had the fourth highest number of executions in the world. Globally, we must protest exceptionally atrocious executions when they take place, such as that of the man recently beheaded and crucified in Saudi Arabia and the rare but utterly unacceptable reality of juvenile executions. Progress is being made: Togo became the 15th country in the African Union to abolish the death penalty.

While the rabbis’ legal rulings effectively abolish the death penalty, they also express the sanctity of human life: “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5).”

Human life itself is sacred beyond comprehension. We should abolish the death penalty not only for the sake of justice. We should abolish it for the sakes of holiness and humility.

Provided by American Jewish World Service, pursuing global justice through grassroots change.