Commentary on Parashat Tzav, Leviticus 6:1-8:36; Numbers 19:1-22

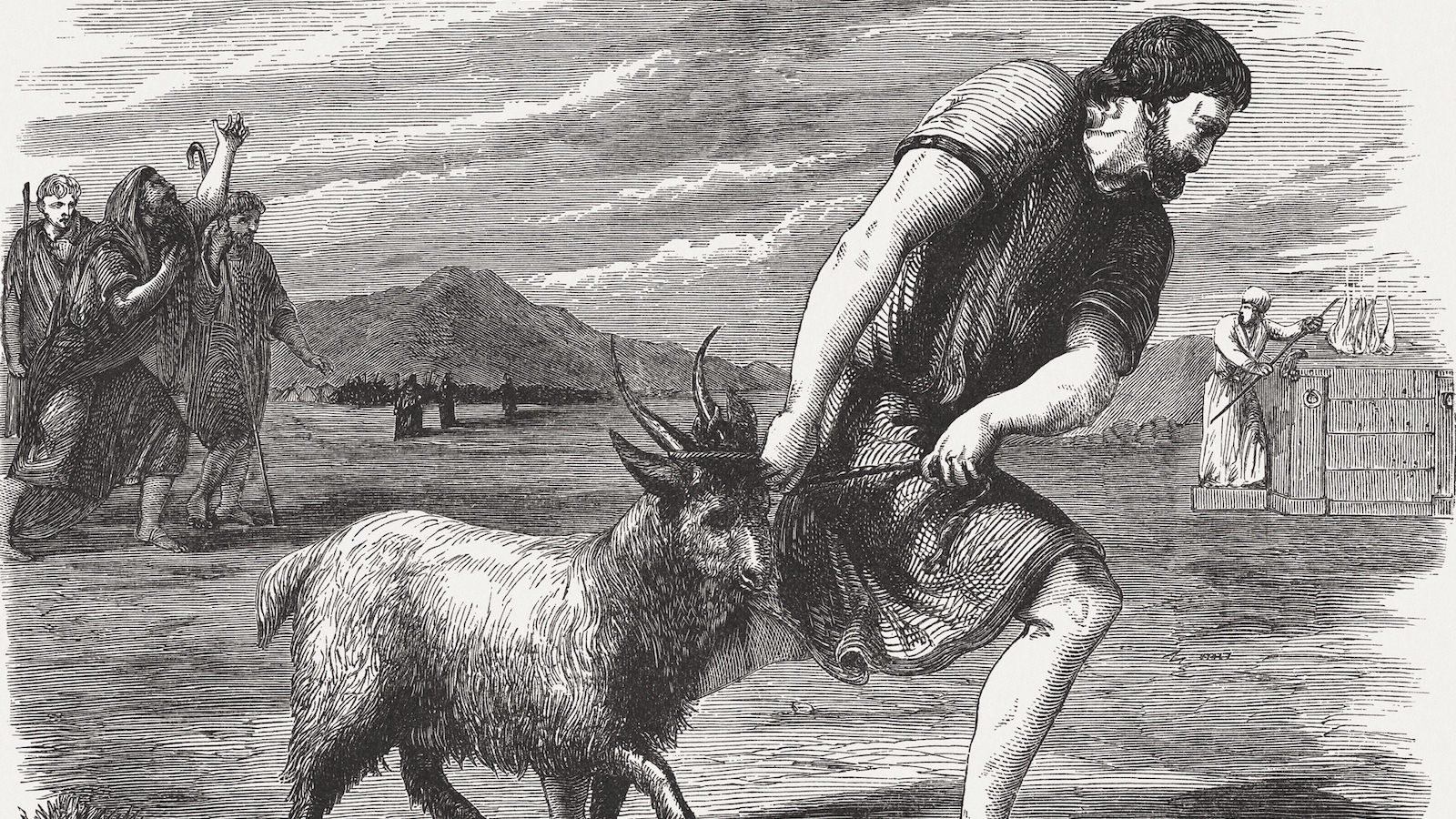

The first part of Parashat Tzav deals with various kinds of korbanot [sacrifices or ritual offerings] that we’ve already heard about in the previous portion. The difference is that last time, Moses was addressing the entire people, instructing them on the sacrifices that anyone might bring, but this time, he is specifically addressing the priests, and giving them their particular instructions. New details include the service of taking the ashes from the Mishkan (tabernacle) out of the camp; rules for the eating of meat; and keeping the “eternal flame” going on the altar. The second part of the parshah describes the ceremony wherein Aaron and his sons were dedicated for service as priests.

Parashat Tzav in Focus

“God spoke to Moses, saying: ‘Command Aaron and his sons, saying: This is the law of the elevation offering… ‘”

What the Text Says

God gives Moses instructions to give to Aaron, the High Priest, and Aaron’s sons, who share the hereditary office of the priesthood. The olah, or elevation offering, is also sometimes called the “burnt offering,” because it was totally consumed on the fire of the altar in the Sanctuary. This kind of offering may be voluntary on the part of an individual, or it may be part of an individual’s atonement for not fulfilling certain commandments, or it may be part of communal holy day observances. The olah offerings could be cattle, flock animals, or doves, sometimes depending on a person’s means.

Drash (Commentary) on Parashat Tzav

Rashi (medieval French commentator) notices something unusual about the first sentence of our portion: Why does God tell Moses to “command” his brother Aaron? Usually, God tells Moses to “speak” or “tell” the people something. In fact, we could say that this is theologically problematic, because it should be God who “commands,” not human beings!

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

So Rashi’s interpretation is that “command” implies zealousness, not only in the present tense but for future generations. In other words, don’t just perform this commandment in a perfunctory or apathetic way, but really pay close attention to getting it right. Rashi then goes on and quotes a teaching from the Talmud:

Rabbi Shimon said: There was a special need for the text to urge zealousness in any case where there was monetary loss.

It’s not immediately clear why Rashi connected Rabbi Shimon’s saying to the burnt offerings, other than the idea of urging energetic attention to the specific task under consideration. Rabbi Abraham Twerski, M.D., a Hasidic rabbi, psychiatrist and prolific author, sees in Rashi’s comment an insight into human nature.

R. Twerski reminds us that the priest’s livelihood and sustenance was based on receiving a portion of other kinds of sacrifices that were brought on a regular basis. According to R. Twerski, the priests had more than enough to eat from all the sacrifices brought to the Temple; only the burnt offerings were totally consumed in the fire. In other words, the burnt offerings represented a “loss” to the priests in the sense that no part of them was available to the priests as food. Theoretically, that shouldn’t have been a problem, or even a consideration, given that they had so much else from which to sustain themselves.

R. Twerski goes on to propose that the reason the Torah uses the language of “commanding” zealous attention in our verse [according to Rashi’s reading] is precisely that the priests could derive no personal benefit from the olah offerings.

It’s not difficult to imagine that the priests paid more attention to the sacrifices that were partially “theirs” than the sacrifices that were a “loss” to them; maybe they even resented having to perform certain rituals purely for others and for God, when so much of their service resulted in immediate material gain for themselves. R. Twerski calls this the trait of “miserliness,” which he defines as an irrational desire for endless material gain — and resentment at the perception of “loss” — even if one’s needs are more than satisfied.

Rashi, as explained above, sees the special “command” of zealous attention as applying not only for the future but for right now. Twerski understands this to mean that even Aaron, the High Priest, who was there with Moses at the Burning Bush and all the way through the Exodus, even Aaron needed this special urging:

He [Aaron] had to be urged and cautioned not be derelict in a service that was of no tangible benefit to him.

Is this even thinkable? Is the High Priest Aaron… one who shared Divine communication with Moses, to be suspect that he would be lax in the Divine service because he would not get a piece of meat from it? Is this not the height of absurdity?

Apparently not. The Torah knows human nature better than we do. In spite of being the greatest scholar and leader, one who is in every other way totally devoted to God, a person may retain a streak of miserliness within himself. The Torah teaches us that no one is immune. Miserliness or stinginess is a character defect which can affect the great and mighty as well as the average person… Regardless of who or what we are, we are vulnerable humans and subject to the most irrational traits. (Abraham Twerski, Living Each Day, essay on Tzav)

Contained within R. Twerski’s interpretation of our verse is a challenge, a challenge to become more “zealously” generous and truly altruistic. I don’t think this means that we should expect emotional perfection from ourselves; our ability to act in a selfless and giving manner varies from time to time.

Rather, I think R. Twerski is asking us to think over those times we’ve secretly resented having to do something for somebody else — or for God — if it didn’t bring us some immediate benefit. Sometimes that benefit is material, and sometimes it is intangible: honor, recognition, power, influence, acclaim. These things are not bad in themselves, but seeking them as the price of “good behavior” can lead to disappointment or anger if they’re not forthcoming.

Thus, even the High Priest was warned: be careful, lest your disappointment at not “getting anything” mar the joyfulness and spirituality of your service. Service to God and others is ideally its own reward, bringing with it the joy of giving and the satisfaction of partnership with God in the work of Redemption.

Provided by KOLEL–The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning, which is affiliated with Canada’s Reform movement.