Commentary on Parashat Noach, Genesis 6:9-11:32

While still in the Garden of Eden, humans, animals, and plants lived in harmony, according to God’s desire for the world. After the Fall, maintaining this harmony became a great toil: the earth outside the Garden was thorny and tough; man and beast became adversaries.

After a few generations all life on the planet had “corrupted (hishchit) its way on the earth.” (Genesis 6:12) In our portion, God decides to wash the slate clean and begin creation over from scratch: “I will blot out from the earth the men whom I created…for I regret that I made them.” (Genesis 6:7) But one man’s righteousness compels God to spare a small sector of life: “Noah found favor with the Lord.” (Genesis 6:8)

Although environmental issues are not directly expressed in the Torah portion, when we take a deeper look at Noah, seeing him through the eyes of Midrash and various rabbinic commentaries, we can discover a portrait of a man who spent his life innovating a lifestyle of environmental harmony and Divine awareness.

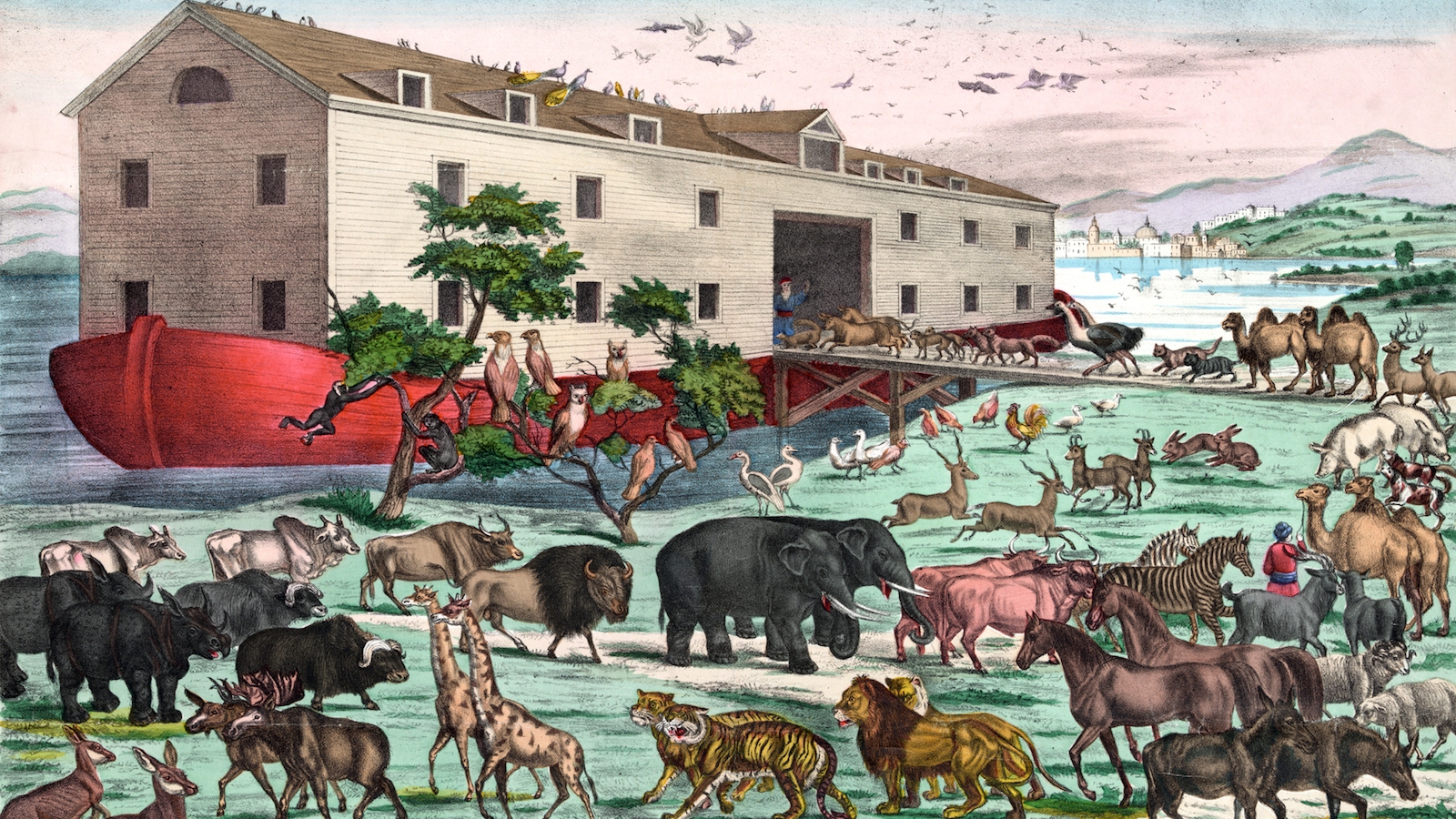

Environmental awareness is an aspect of the known as Bal Tashchit–Do Not Destroy. Noah, the one man who had not corrupted the world, became the pioneer of Bal Tashchit in the world–when he built the , the vessel that would preserve the planet’s animal life in the face of the total destruction of the environment.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Noah and his family faced incredible hardship and challenge as they fought the tide of destruction. A fresh look at the life of Noah can provide us many lessons as we strive to bring our world back to a state of holy balance. What can we learn from Noah’s efforts?

The Patient Educator

Caring about the environment requires patience and forethought. The (Genesis Rabbah 30:7) says that 120 years before the Flood, Noah actually planted the trees from which he would take the wood for the ark (no old-growth logging here)! Aware of the massive resources that his project would demand, Noah tried to be as self-sustaining as possible.

Noah hoped that his example could help inspire others to live more conscious and righteous lives. According to one opinion, Noah spent 52 years building, deliberately working slowly so that the people would take note, repent of their destructive ways, and prevent the coming catastrophe.

Hands-On Dirty Work

Protecting God’s world requires hard, sometimes unpleasant work. Noah didn’t just load up the ark and sail worry-free–he worked without rest during the entire year of the Flood. For example, according to the Midrash Tanhuma, “throughout those twelve months, Noah and his sons did not sleep, because they had to feed the animals, beasts, and birds.”

But feeding thousands of animals was the cushy job. As the Talmud (Sanhedrin 108b) explains, the ark had three levels, one for Noah and his family, one for the animals, and one for the waste–tons upon tons of animal droppings. The rabbinic sources debate the layout of the ark and the design of Noah’s waste-management system, but one thing remains clear–Noah’s family spent a lot of their time shoveling manure.

Whether they systematically removed it from the ark, stored it in a designated waste facility, or found practical use for it, we see that Noah toiled to maintain the cleanliness of the ark. While such work is not always enjoyable, Noah’s lesson is that the benefits of a clean, healthy living space over a filthy, foul-smelling environment are certainly worth the effort.

We All Share the Same Lifeboat (or Ark)

Another lesson we can learn from Noah is that it helps to see the world as a closed, integrated system. Noah and his eight-person crew maintained a sort of proto-BioDome inside the ark, struggling to preserve a functional level of ecological balance in the most challenging of situations.

Within such a system, every action has a significant impact and ramification, and individual elements can be aligned so as to strengthen and assist one another. For example, in our contemporary world composting food waste reduces landfill volume and then creates rich soil for home-grown, organic vegetables. Using public transportation in congested areas reduces pollution while cutting down on frustrating traffic. Less traffic, cleaner air, and time to relax on the bus or train all contribute to less personal stress. Riding a bicycle to work does all these while significantly improving health.

Partnership with the Land

Noah’s construction of a giant, floating ecosystem was proof enough of his excellence as an environmental innovator. After the Flood, he reinvented himself again as an agricultural pioneer.

At his birth, Noah’s father predicted that Noah would relieve mankind from the curse on the land that came with Adam and Eve’s expulsion (Genesis 3:17-19, 5:29). According to Genesis 9:20, “Noah began to be a man of the soil” after he left the ark. The Midrash explains that Noah revolutionized farming techniques to soften the backbreaking toil that had been the way of the land since the Fall.

Noah may have used the massive stores of dung on the ark to compost and revitalize the land, which had lost its top 12 inches of topsoil in the Flood. By thus easing the burdens of man and the soil, he truly earned his name,”rest.” Overall, Noah’s relationship with the land was harmonious and productive, not adversarial or injurious to the planet or to his own well-being.

As beneficiaries of the earth’s produce and descendants of Noah, we should ensure that the world’s agricultural workers are supported by both modern technologies and modern social values. Like Noah, modern farmers can promote agricultural techniques that keep the land viable for future generations.

We must not fill our breadbasket via the suffering of those less fortunate than ourselves, or at the expense of a healthy, fruitful future. The fact that we can eat meat does not necessarily mean that we must, and certainly does not mean that we must eat it every day! Exploring the fruits and vegetables of the land, like Noah, can be exciting and creative while promoting our own health. When we do eat meat, it should be from farms that share our concerns for a healthy world and that respect God’s creatures, all of whom live under the sign of the rainbow.

Faith in Humanity

While Noah strove for a gentle environmental harmony, the people of the earth arrogantly saw themselves engaged in a battle with God and the forces of nature. When they saw him building the ark, the people told Noah, “If God brings the Flood up from the earth, we have iron plates with which we can cover the earth!” (Sanhedrin 108b)

In spite of such skepticism, Noah stayed the course, and even maintained faith in humanity. We see from the Torah that he did not board the ark until after the Flood had already begun, hoping that people would change their ways and thus prevent the destruction.

For Noah, the ark was an unfortunate but necessary solution to a global crisis. Even when all signs were grim, he maintained his faith, greeting every challenge with further innovation. So too must we continue to strive for a better tomorrow, educate others about environmental issues, and believe that our actions, on every level, can make a difference.

When we step outside after a rainstorm and see the rainbow in the sky, we remember God’s promise to Noah, and we know that we are not alone in our efforts.

Provided by Canfei Nesharim, providing Torah wisdom about the importance of protecting our environment.