I was hardly surprised, in 2003, by the commentaries occasioned by the hundredth anniversary of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s birth. He was, after all, a Nobel laureate and the Yiddish writer most Jewish-American readers know. Certain Yiddishists, however, felt duty bound to remind people of just how much Singer was not a traditional Yiddish writer how he wrote about an Old World that never was, how Chaim Grade, author of The Yeshiva, was much more qualified to win a Nobel prize, how Singer was–no other word would do–a pornographer, and most cutting of all (at least for Yiddishists) how his Yiddish was hardly refined.

Singer had heard all these charges during his lifetime and he made no bones about the fact that he regarded most Yiddish writing as both sentimental and provincial. Moreover, he made no apologies if certain timid souls were shocked by the X-rated content in some of his fiction. Singer explored the darker sides of human nature, which meant that he wrote about betrayal, greed, murder, and sexual appetite. The same can be said for most great writers, but when Singer chronicled sexuality in both the Old World, and increasingly as his career unfolded, in the New World as well, many Yiddish readers were embarrassed.

And this was before Singer’s stories appeared in Playboy.

Early Career

Isaac Bashevis Singer came to America in 1935, already known among Yiddish readers in Poland for Satan in Goray, a quasi-historical novel about zealots who follow a false messiah and, in the process, turn traditional religious values upside-down.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Singer was also well known (if not particularly “famous”) because his older brother was Israel Joshua Singer, the novelist and staff writer for the Forward, New York City’s leading Yiddish newspaper. Singer also wanted to be a Forward writer (a regular paycheck was, after all, a regular paycheck), but Abraham Cahan, the paper’s editor, nixed the deal. There was no future, he thought, for Yiddish or Yiddish newspapers once the city’s immigrant population learned–as they must–how to speak and read English. So, Singer worked on a piece-by-piece basis, submitting stories about dybbuks (malicious spirits) allegedly spotted in the Bronx, while working on his own stories.

Meanwhile, his wife Alma got a job (and a regular paycheck) at Lord & Taylor’s. Singer stayed home and wrote, often in bed, propped up by pillows.

Gimpel the Fool

Indeed, one of his most anthologized stories, “Gimpel the Fool,” was written this way and later sold to a collection of children’s fiction for something like $25 (accounts about the precise amount differ).

What matters in terms of Singer’s American reputation is not how many Yiddische kinder heard the story at bedtime but the fact that critic Irving Howe so admired Singer’s odd tale of innocence and art, corruption and imagination, that he sent it to Saul Bellow so he could translate it into English.

After Bellow translated the story, it went back to Howe who submitted it to the editors of Partisan Review. Singer’s story of a boy easily deceived by his classmates, and of a man later cuckolded by his wife, redefined the dimensions of the schlemiel. Gimpel, the holy fool, becomes a wise man and, more important, a storyteller: “Going from place to place, eating at strange tables, it often happens that I spin yarns–improbable things that could never have happened–about devils, magicians, windmills, and the like.”

In describing himself, Gimpel also describes his creator.

The story was published in a 1953 issue, and the rest, as they say, is history. During the mid-1950s Partisan Review was the most influential magazine of its kind; self-respecting intellectuals read it from cover to cover. Being in its pages usually assured a writer a measure of fame. That was certainly the case with I.B. Singer. A decade after “Gimpel” appeared, Singer was publishing regularly in The New Yorker and, yes, Playboy.

Singer the Celebrity

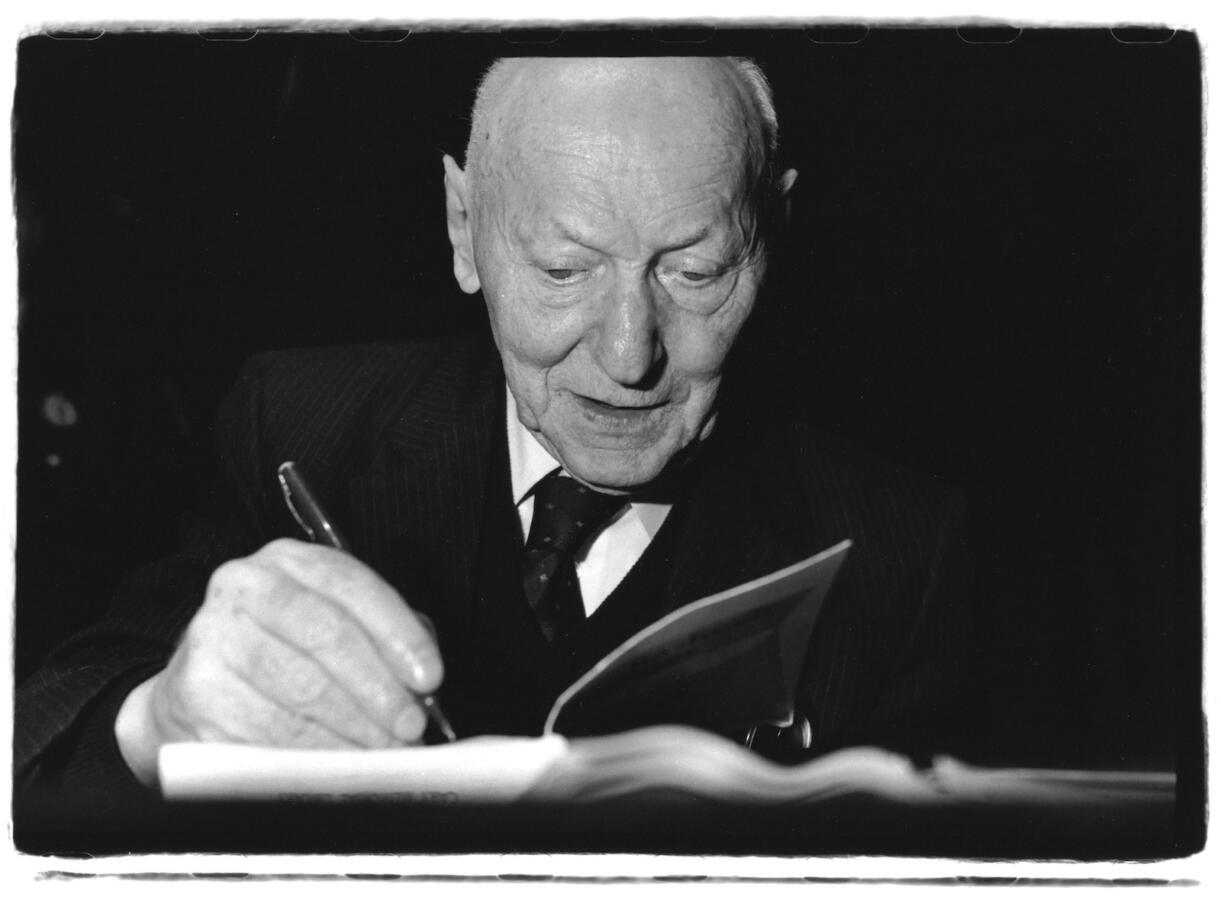

As his fame increased, Singer also joined the lecture circuit, charming audiences at synagogues, Jewish community centers, and college campuses. He was especially memorable during the question-and-answer sessions that followed his readings. Singer was, in effect, the genial grandfather that most people never had: Jewish to his bones, disarming, and full of quick, funny quips.

Singer wrote hundreds of short stories, many of which were later published in collections (e.g. Short Friday [1964], Old Love [1979]), a handful of novels (e.g. The Family Moscat [1950], Enemies, a Love Story [1972]), and memoirs such as In My Father’s Court (1956) and Lost in America (1981). He was a master storyteller and a writer who could fix a character with a few quick brushstrokes. Ghosts and dybbuks, imps and devils, were prominently featured in his fiction, as were the complications that survivors of the Holocaust faced when they made their way to America. Singer took in the whole landscape and made it, fictionally, his own.

A Child-Like Perspective

However, nothing cuts to the heart of his writing more than the realization that Singer remained child-like all his life. He asked questions: why do people get sick and die?; why is life so cruel?; why do good people often suffer at the hands of evil doers? Singer continued to ruminate about these basic questions long after most people had put them aside as impractical.

There is, however, a considerable difference between being childish and being child-like. Singer was the latter, despite the fact that, in truth, he was a darkly brooding, eminently sophisticated man and not merely the clever fellow who made people laugh at the 92nd Street Y.

In some of his stories the world is likened to a slaughterhouse; in others, jealousy drives characters mad. Shadows on the Hudson (1998), a novel published in Yiddish and only translated into English after his death, is filled with philosophical discussions by Holocaust survivors living in Manhattan. Their ruminations include sharp criticisms of American Jewry.

For all his apparent naivete, Singer guarded his reputation and carefully managed his career. Although gossip-mongers whispered about his mistresses, most of whom, the rumors went, doubled as his translators, the fact of the matter is that most of his translators were exploited financially rather than sexually. A possible reason for this, beyond the fact that Singer was, in most respects, a cheapskate, is that Singer irrationally feared being destitute and never felt entirely comfortable with the money his stories made.

All of this is very different from the persona he put on when he walked out on stage. That Singer is forever lost to us, but Singer, the writer of exquisite paragraphs, remains–not only in the vast amount of material already translated into English, but also in the large cache of sketches and short stories that will likely find their way into print during the next few decades.

Read Isaac Bashvevis Singer’s obituary from July 1991 here.

Our partner site, Hey Alma, published the English translation of Singer’s”Apudzhas Came To Say Goodbye.” Click here to read the short story.