Will humans ever land on Mars? Quite a number of people are trying to make it happen.

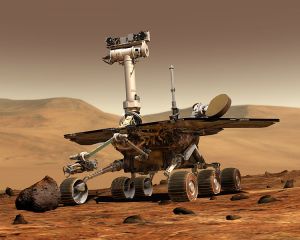

Buzz Aldrin has just published a book Mission to Mars: My Vision for Space Exploration. About half a million people are expected to apply for a one-way trip to Mars through the Dutch company “Mars One.” And even though it was a robot doing the landing, over 3 million people watched Curiosity land on the red planet.

Over 50 years ago, the nation (and the world) were riveted by NASA’s attempts to land a person on the moon, and bring him back safely to the earth. And when NASA succeeded, the whole world felt a sense of pride and awe when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped out of the LEM and onto the Sea of Tranquility.

In its way, space travel is its own reward. Yes, the space program has provided us with concrete benefits: GPS navigation, meteorological forecasts, and even treatments for osteoporosis. But what it truly offers us is inspiration and a drive to expand our knowledge.

Neil de Grasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium, reminds us that the real value of space travel is how it captures our imagination, and how it motivates us to continue learning:

My favorite quote, I think it was Antoine Saint-Exupery who said, “If you want to teach someone to sail, you don’t train them how to build a boat. You compel them to long for the open seas.” That longing drives our urge to innovate, and space exploration has the power to do that, especially when it’s a moving frontier because all traditional sciences are there.

We humans are naturally curious creatures — we are born to explore. A mission to Mars excites us because we simply don’t know what we’ll discover, or how exactly it will add to our knowledge, or what new technologies will arise as a result. Even if we don’t immediately sense its benefits, it still has value, because the journey of learning is its own reward.

That’s the same message we get on Shavuot, our celebration of Torah, because the study of Torah, too, doesn’t always provide an immediate return on its investment. Instead, we study Torah lishmah, for its own sake.

Why? Because Torah is not designed to train us how to build a boat. It is designed to make us long for the open seas.

Jewish learning is never supposed to give us a final and definitive answer. Instead, it is supposed to inspire us, and to push us to explore beyond what we already know. Rabbis Michael Katz and Gershon Schwartz even titled a book

Swimming in the Sea of Talmud

because Jewish study leads us into the vast, challenging, and compelling unknown, which we do for the pure joy of learning something new. As they teach us, when we learn one text,

…there are a dozen new questions arising from [it]: Can this lesson be applied to other, similar situations? Is this lesson still applicable today? What would the Rabbis of the Talmud say to our particular situation, which differs slightly from the case they presented? Is the conclusion reached and the lesson derived from the text the most relevant and meaningful message? (Katz and Schwartz, 6-7)

True learning never stops; it pushes us out ever-farther into uncharted territory. As both space exploration and Torah study show us, each new discovery spurs new lines of inquiry; each new challenge forces us to create innovative solutions; each new venture helps us push the boundaries of knowledge.

Now, it is true that as vast as the open sea may be, it is not infinite. And neither, most likely, is space.

But human curiosity — our drive to explore and learn and grow — just might be.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.