Summer is over and the excitement of my son Jonah’s longest ever stay at sleep-away camp, three weeks, is starting to feel like a distant memory, an anomaly even. In other words, fall is here and things are returning to what feels, for better or worse, like normal for a family with a child with autism.

If summer seemed full of promise, fall feels more precarious. School has started. There are buses to be met, lunches to be prepared. And the leaves are changing. The fickleness of the weather—balmy one day, freezing the next—is not something I ever paid much attention to as a lifelong Montrealer. But most kids on the autism spectrum don’t like change and Jonah’s no exception. That includes changes in the temperature. Some mornings, he and I end up in drawn-out, complicated debates about the appropriateness, say, of wearing shorts and sandals on a chilly October morning.

This time of year, the Jewish High Holidays, also add to the feeling that we’re back on the same old autumnal schedule. My family remains actively involved with our Reform Temple, often without me, I confess. For the start of Rosh Hashanah, for instance, Cynthia and Jonah showed up along with the rabbi and other members of the congregation at a pond in a neighborhood park to participate in Tashlich or the ritual of casting away our sins. As Cynthia described it to me later, the ceremony began with some songs and prayers and the usual-suspect list of sins: deception, selfishness, arrogance, that kind of thing.

Everyone had also shown up with bread crumbs—symbols of their transgressions—which they were expected to throw into the pond. Before doing this though, each person went off on his or her own. It was an opportunity to meditate on the past year and the year to come. “I liked that part,” Cynthia told me later. “But Jonah really got into throwing the bread into the water.” Apparently, he had used his meditation time to compile a rather extensive list of kids he’d bugged on the school bus. Cynthia did her best to keep pace, but it wasn’t easy. As Tashlich ended, Jonah, with his own typically dramatic flair, threw one final and substantial fistful of bread crumbs into the pond, exclaiming as he did: “I cast away the sin of being a pest.”

Fall, more than any other season, reminds me that I have to be aware of how our son interacts with the world and how the world responds to him. The world, I’m afraid, does not always respond well. Lately, I’ve noticed more jokes about “short buses” – the kind of school bus that picks up Jonah every day—and the kids who ride them than in recent years. I’ve heard these jokes repeated, in one hurtful form or another, on TV shows, spoken by beloved characters, on podcasts from respected cultural and political commentators, even at a speech at a wedding of close friends we recently attended. I know it is easy, sometimes reflexive, to make fun of people who are different. I just wish it weren’t. I wish that this commonplace, everyday kind of intolerance was one transgression we all worked harder to cast off.

People are mostly nice, Cynthia wanted me to add here, but there are still looks and comments she and I deal with or, more likely, ignore every day when we are out in the world with Jonah. They happen everywhere, even in the most unlikely places. Here’s an example of an experience Cynthia and Jonah had the other day at Temple. The story is related in my wife’s words:

“I was looking around at the family service and all the beautiful children, especially a little girl snuggling with a boy and an even littler girl. I thought how nice it was for them to have that cosy time together and to get a good feeling for the service. Then this sweet little girl turned around and told my son, who was singing the prayer (correctly, I might add), to be quiet. Then my son started talking to himself and writing with his finger (a kind of stim he uses to calm himself). The little girl looked at her friends and made the finger sign for ‘crazy’ about my son. I am not sure if he noticed or not.”

Incidentally, Cynthia emailed this story to our rabbi, who included the passage in her recent Rosh Hashanah sermon on tikkun olam. To Cynthia’s story, the rabbi added: “There is so much that needs healing. But our tradition teaches that that is precisely why we are here and why our existence is worthwhile: to be God’s hands in this world.”

Last year, Cynthia started a special needs committee at the Temple. The idea remains a simple one – help make a place already welcoming, by definition, become more so.

“I don’t know how to help these children be more compassionate and be enriched by people who are different,” Cynthia concluded in her email to the rabbi, “but that is the goal.”

Not a bad one for this time or any time of year. Not a bad time, either, to cast off the normal ways of thinking about my son and others like him and get to work on fashioning a new normal.

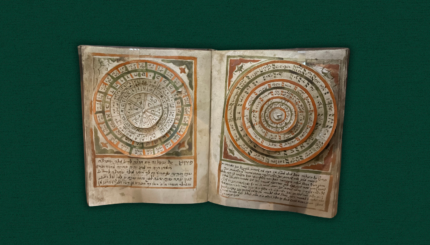

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

Tashlich

Pronounced: TAHSH-likh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, literally “cast away,” tashlich is a ceremony observed on the afternoon of the first day of Rosh Hashanah, in which sins are symbolically cast away into a natural body of water. The term and custom are derived from a verse in the Book of Micah (7:19).