“To celebrate freedom and democracy while forgetting America’s origins in a slavery economy is patriotism a’ la carte.”

A recent article by Ta-Nehisi Coates in the Atlantic Monthly outlines the argument for reparations to be paid to African Americans for the injustices of slavery, and the subsequent economic disadvantage and discrimination they have suffered for more than a century. As convincing as Coates’ is regarding the systemic injustice meted through the Jim Crow period, and the way decades old housing discrimination continues to hold back blacks even today, there is one question that nags: “why should I be paying for reparations on something I had nothing to do with?”

I didn’t enslave anyone, nor has anyone I know. While my family actually does have ties in the US dating back to the mid-1800s, I have no reason to think they were involved in slavery. On my wife’s side, her father immigrated from Germany as a child in the 1950’s, and her mother’s family fled Russia in the early 1900s. What culpability could we possibly have in the enslavement of Africans from 1619-1865?

Coates answers with this:

A nation outlives its generations. We were not there when Washington crossed the Delaware, but Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s rendering has meaning to us. We were not there when Woodrow Wilson took us into World War I, but we are still paying out the pensions. If Thomas Jefferson’s genius matters, then so does his taking of Sally Hemings’s body. If George Washington crossing the Delaware matters, so must his ruthless pursuit of the runagate Oney Judge.

If we are Americans, and we benefit from being American, want to remain American and might even be proud to be American, we need to own the whole thing. We can’t take the Constitution without slavery; we can’t have 21st century Manhattan without 19th century Mississippi.

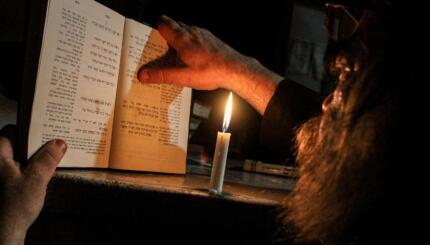

And this is exactly what we reenact every year on Tisha B’Av. We sit on the floor, eat ashes and weep. We read Lamentations with its horrific descriptions of the siege of Jerusalem and the city’s ultimate destruction. Wanton hatred destroyed one Temple, and lasciviousness destroyed the other. We do this every year, but what did I have to do with the Temple being destroyed? Those weren’t my sins. I can’t even relate to the concept of there being a functioning Temple, and now I’m expected to feel remorseful and seek atonement for its destruction? I wasn’t there! Can’t I just have a Passover Seder, read Megillat Esther and dance on Simchat Torah without having this random day of mourning in the middle of the summer?

This idea of complete ownership over our heritage isn’t only relevant when considering problematic historical events. The same applies to our relationship to the modern State of Israel. As someone who loves Israel and prays for her future, there are some things I just want nothing to do with, and I think that’s true for everyone. Whatever your politics, there are things you love about Israel and things you hate about it. Whether it’s Haredim serving in the IDF, bombs falling in Gaza, misogyny in the workplace, income inequality or a myriad of other issues—there is something about Israel that makes you upset. There is something about Israel you wish you could disown. We all have an obligation to work on changing these things, but we don’t have the luxury of pretending that the Israel we love and support doesn’t include them. We can’t have the hike through Ein Gedi without grappling with the armored bus to Ariel. We can’t have the yeshivas in Jerusalem and the cafes in Tel Aviv while trying to ignore the conditions in Ramla or the deportations of Ethiopian refugees.

Orthodox Feminists are often asked (from both the left and the right) why we remain Orthodox. If we are so troubled by certain interpretations and applications of halakha, why not just jump ship? Wouldn’t it be so much easier to keep the parts we like and drop the parts we don’t? The answer is obvious. This is our heritage, and this is our history. We understand that as members of this kehillah, community, we can’t ignore the problems. We will remain committed to the halakhic process, while working to fix it, because it is ours—for better or worse.

Tisha b’Av is the time to reflect on the tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people, but not just for the sake of self pity. It is our opportunity to understand how we went down a path towards destruction, and to identify the tikkunim, improvements, we can implement in our own lives to avoid the same fate in the future.