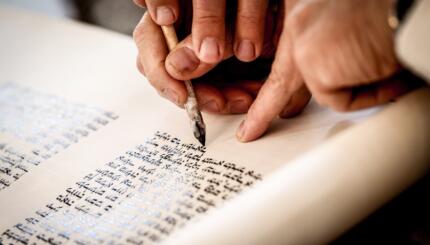

Torah scrolls are the centerpiece of Jewish ritual life. A kosher Torah scroll — one fit for ceremonial use — must be written by a trained Jewish scribe according to a strict set of guidelines. All the words must be written accurately in special calligraphy on pieces of animal parchment that are then sewn together.

Torah scrolls are painstakingly created using materials that are meant to last, but — like the rest of us — they do not live forever. They require maintenance and repair along the way to keep them fit for ritual use. What kinds of things make a scroll pasul — unfit for use? What must be attended to by a scribe to get the scroll back into regular use? Here are ten examples.

There’s a rip right through the text

Let’s start with an obvious one. Sometimes, a Torah scroll can develop a tear right through the text of a column. This can happen if it is dropped or improperly handled during hagbah or when unfurled during a Simchat Torah ceremony. Taping it back together does nothing to change its status as pasul. Typically, an entire new yeriah (sheet) must be rewritten and sewn into the scroll in its place. A trained scribe must write the new yeriah but community members may sew the sheet in place with guidance.

Words run together

Letters of the same word are meant to be “a hairsbreadth apart” but not touch, and words must be separated by the width of the letter yod, which is the smallest Hebrew letter. (This width will vary depending on the size of letters in each particular scroll.) If words are too close, causing them to look like one word instead of two, this is a problem and must be fixed.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

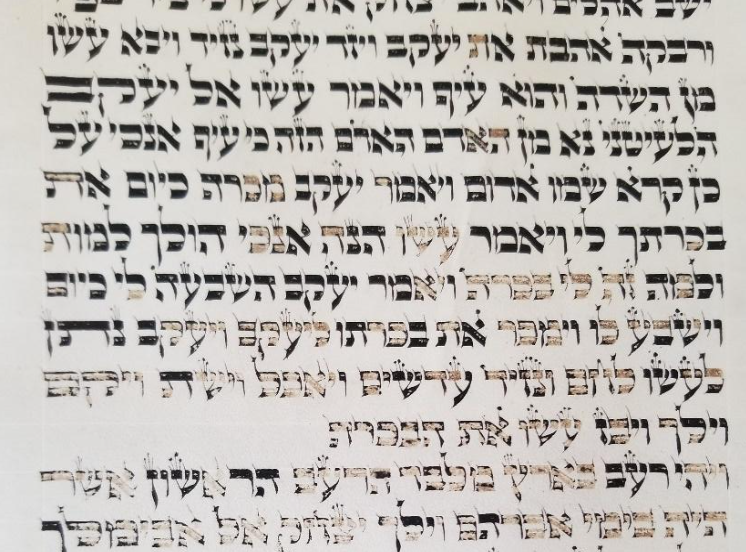

A spelling mistake

Yes, spelling counts. It doesn’t matter whether the meaning of the word is clear. In fact, some words are spelled differently when they appear in different places in the scroll. For example, the word mezuzot is sometimes spelled with its final vav (for example, Deuteronomy 11:20) and sometimes without (for example, Deuteronomy 6:9), and the scribe has to copy it correctly in each instance. All mistakes in words or letters are an issue: If just one letter is missing or one letter is added anywhere in the scroll, it is pasul until fixed.

What’s that letter?

Each Hebrew letter has a proper form (with a wide range of styles), and cannot look too much like another letter. If a reish isn’t rounded and looks too much like a dalet, which is squared on the top right side, the letter, and therefore the entire scroll, is pasul. If it’s somewhere in the grey area — meaning the reish might look too much like a dalet — a child who is “not too bright nor too dull” is asked to identify it. Whatever the child says, goes: If they determine it’s a reish, it’s officially a reish and needn’t be fixed.

The ink flaked off…

With use, and over time, letters begin to fade or chip away (especially in sections that are read multiple times a year). For a Torah scroll to be kosher, its letters must be present. A bit of fading is normal and acceptable, but if a word, letter or even a portion of that letter — depending on the particulars — has chipped away, the scroll is pasul and those letters must be re-inked.

… but the imprint is still legible!

Sometimes, when the ink of a letter has chipped off, the shadow of that letter is fully visible, because the ink has left an imprint in the parchment. This is still considered pasul, and the letter must be re-inked. However, if the tagin — those small crowns that adorn certain letters — fade away, the scroll is still kosher.

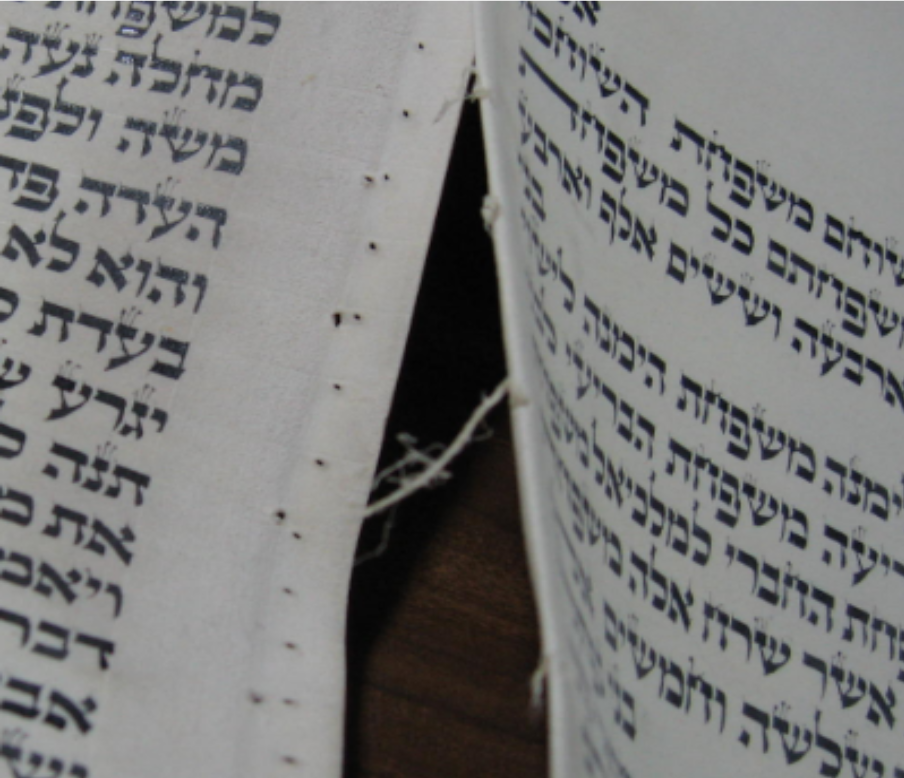

A seam has come apart

If a seam is partially undone, it should be sewn as soon as possible, but the scroll is not necessarily considered pasul. That depends on how many stitches are left intact, as well as whether the week’s reading is in the same book as the unraveling seam. But if a seam that has been partially undone finally comes apart (and you now have two scrolls instead of one) it is pasul and the seam must be resewn using a kosher thread called gid.

The scribe formed a letter by taking something away

The principle of hak tochot holds that letters must be positively formed, meaning that a letter cannot be created by taking something away. For instance, if the scribe accidentally wrote the letter hey (ה) in place of a dalet (ד), the scribe may not simply scratch off the letter’s left leg, thereby turning it from a hey into a dalet. The community must trust the scribe not to do this, because it is impossible to know whether the rule was followed by visually examining the text.

Vowels were added to help a bar mitzvah student

Reading from the Torah scroll is not easy, and learners may wonder why there aren’t vowels or cantillation marks. The reason is that both were conceived generations later to help people pronounce and interpret the text. Marks such as vowels or trope (cantillation) signs, even in pencil, render the scroll pasul and must be erased for the scroll to be kosher.

A robot wrote it

If you programmed a robot to write a Torah scroll (don’t laugh, this was on display at the Berlin Jewish Museum), the scroll is not kosher for ritual use. One of the basic premises in sacred writing is that the scribe must write with intention, and with special intention when forming the name of God. Since we have not yet figured out how to imbue AI with consciousness, they cannot write Torah scrolls. However, using AI to check for errors is a helpful tool.