Passover celebrates the ancient Exodus of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt. Here are nine things you might not have known about this major Jewish festival.

1) In Gibraltar, There’s Dust in the Haroset.

The traditional haroset is a sweet Passover paste whose texture is meant as a reminder of the mortar the enslaved Jews used to build in ancient Egypt. The name itself is related to the Hebrew word for clay. In Ashkenazi tradition, it is made from crushed nuts, apples and sweet red wine, while Sephardi Jews use figs or dates. But the tiny Jewish community of this small British territory at the tip of the Iberian Peninsula takes the brick symbolism to another level, using the dust of actual bricks in their recipe.

2) Abraham Lincoln Died During Passover.

The 16th American president was shot at Ford’s Theatre on a Friday, April 14, 1865, which coincided with the fourth night of Passover. The next morning, Jews who wouldn’t normally have attended services on the holiday were so moved by Lincoln’s passing they made their way to synagogues, where the normally celebratory Passover services were instead marked by acts of mourning and the singing of Yom Kippur hymns. American Jews were so affected by the president’s death that Congregation Shearith Israel in New York recited the prayer for the dead — usually said only for Jews — on Lincoln’s behalf.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

3) Arizona Is a Hub for Matzah Wheat.

Hasidic Jews from Brooklyn have been increasingly sourcing wheat for their Passover matzah from farmers in Arizona. Excessive moisture in wheat kernels can result in fermentation, rendering the harvest unsuitable for Passover use. But rain is scarce in Arizona, which allows for a stricter standard of matzah production. Rabbis from New York travel to Arizona in the days leading up to the harvest, where they inspect the grains meticulously to ensure they are cut at the precise moisture levels.

4) At the Seder, Persian Jews Whip Each Other with Scallions.

Many of the Passover seder rituals are intended to recreate the sensory experience of Egyptian slavery, from the eating of bitter herbs and matzah to the dipping of greenery in saltwater, which symbolizes the tears shed by the oppressed Israelites. Some Jews from Iran and Afghanistan have the tradition of whipping each other with green onions before the singing of “Dayenu.”

5) Karaite Jews Skip the Wine.

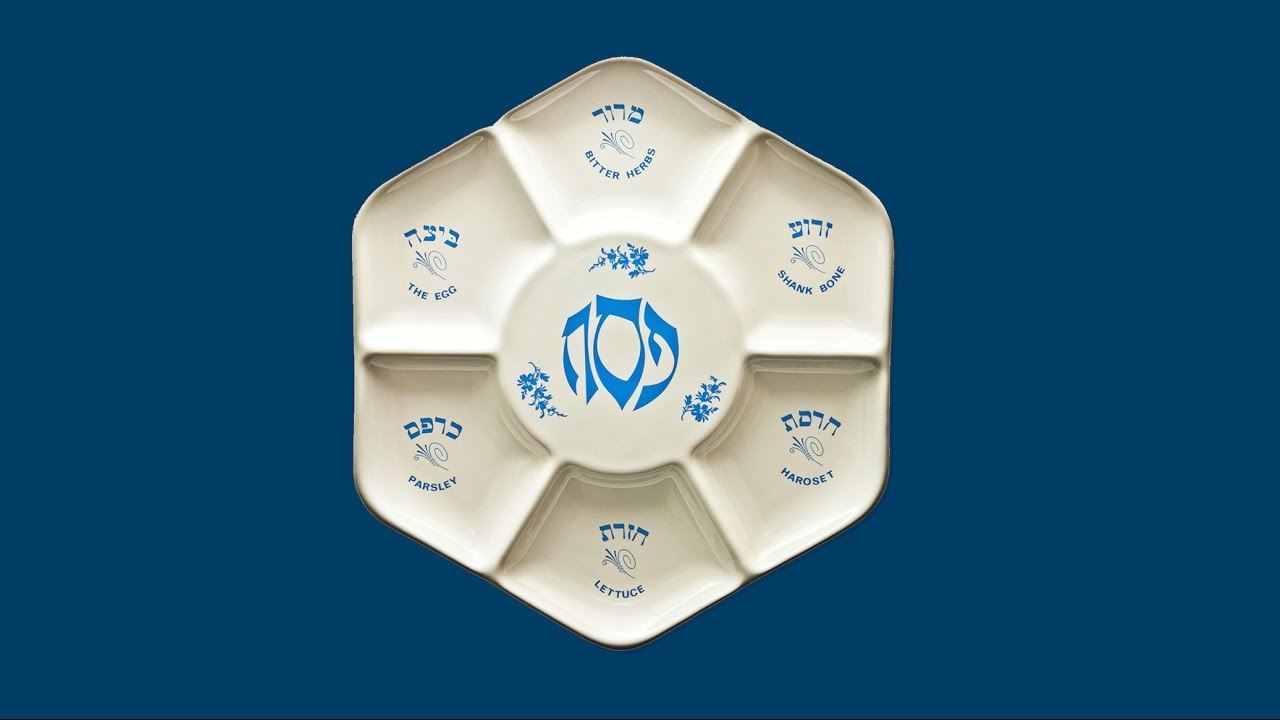

Karaite Jews reject rabbinic Judaism, observing only laws detailed in the Torah. Which is why they don’t drink the traditional four cups of wine at the seder. Wine is fermented, and fermented foods are prohibited on Passover, so they drink fruit juice instead. (Mainstream Jews hold that only fermented grains are prohibited.) The Karaites also eschew other staples of the traditional seder, including the seder plate, the and charoset. Their maror (bitter herbs) are a mixture of lemon peel, bitter lettuce and an assortment of other herbs.

6) Israeli Jews Have Only One Seder.

Israeli Jews observe only one Passover seder, unlike everywhere else where traditionally two seders are held, one on each of the first two nights of the holiday. Known as yom tov sheni shel galuyot — literally “the second festival day of the Diaspora” — the practice was begun 2,000 years ago when Jews were informed of the start of a new lunar month only after it had been confirmed by witnesses in Jerusalem. Because Jewish communities outside of Israel were often delayed in learning the news, they consequently couldn’t be sure precisely which day festivals were meant to be observed. As a result, the practice of observing two seder days was instituted just to be sure.

7) You’re Wrong About the Orange on the Seder Plate.

Some progressive Jews have adopted the practice of including an orange on the seder plate as a symbol of inclusion of gays, lesbians and other groups marginalized in the Jewish community. The story goes that the practice was instituted by the feminist scholar Susannah Heschel after she was told that a woman belongs on the synagogue bimah, or prayer podium, like an orange belongs on a seder plate. But according to Heschel, that story is false. In that apocryphal version, she said, “a woman’s words are attributed to a man, and the affirmation of lesbians and gay men is erased. Isn’t that precisely what’s happened over the centuries to women’s ideas?”

8) “Afikomen” Isn’t Hebrew.

For many seder attendees, the highlight of the meal is the afikomen — a broken piece of matzah that the seder leader hides and that the children in attendance search for; the person who finds the afikomen usually gets a small reward. Most scholars believe the word “afikomen”derives from the Greek word for dessert. Others say it refers to a kind of post-meal revelry common among the Greeks. Either theory would explain why the afikomen is traditionally the last thing eaten at the seder.

9) For North African Jews, After Passover Comes Mimouna.

Most people are eager for a break from holiday meals when the eight-day Passover holiday concludes. But for the Jews of North Africa, the holiday’s end is the perfect time for another feast, Mimouna, marking the beginning of spring. Celebrated after nightfall on the last day of Passover, Mimouna is marked by a large spread of foods and the opening of homes to guests. The celebration is often laden with symbolism, including fish for fertility and golden rings for wealth.