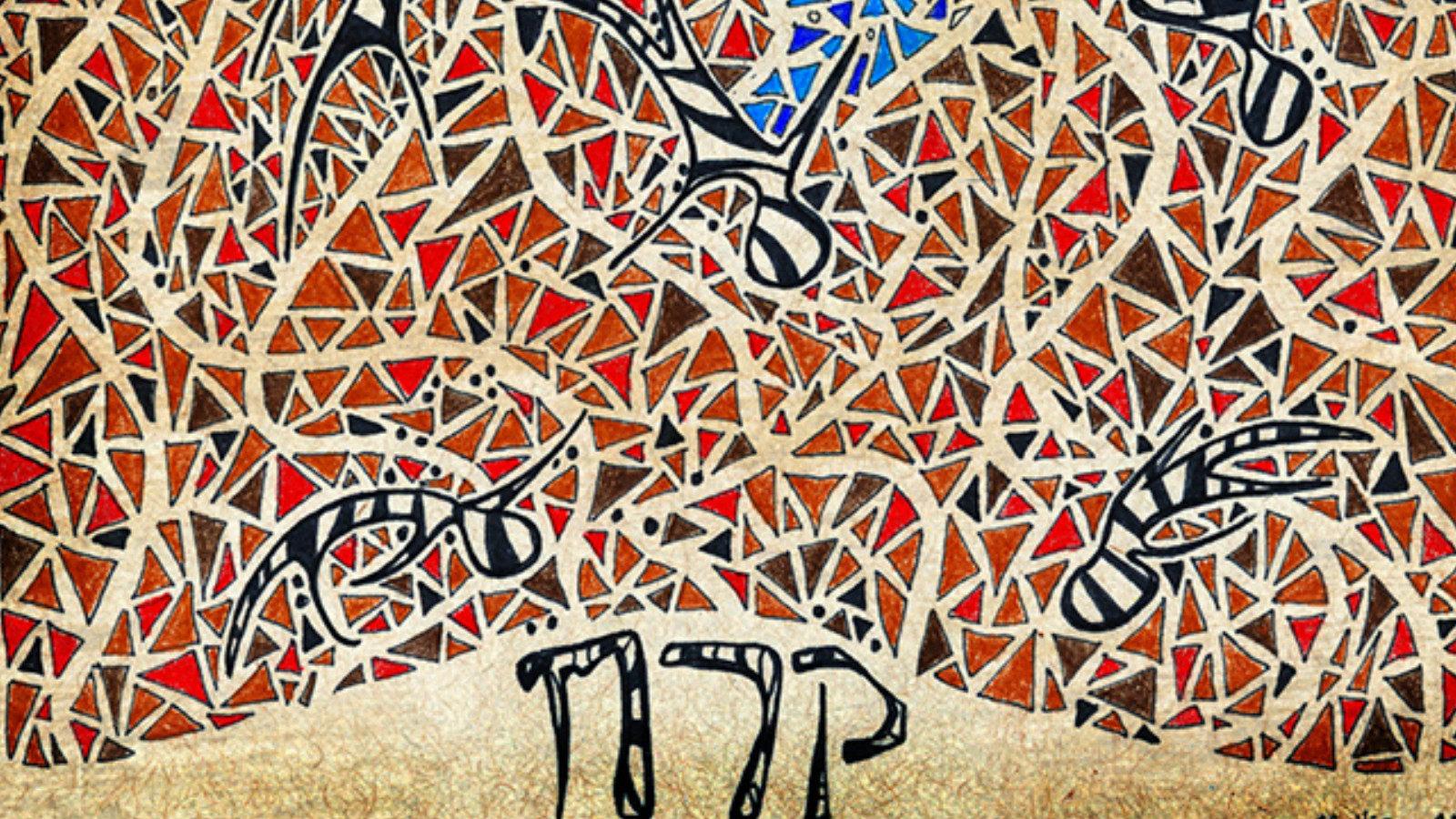

Commentary on Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1-18:32

The core event in the Torah portion called Korach is a challenge to Moses’ authority from the man from whom the Torah portion takes its name. Korach gathers a group of malcontents, and together they assemble against Moses and his brother Aaron, saying “You have gone too far, for all of the community are holy, and God is in their midst; why do you raise yourself above them?”

In response, Moses falls on his face before God. (As my ALEPH co-chair Rabbi David Evan Markus wrote last year on My Jewish Learning, that’s an essential spiritual practice for anyone in leadership.) Then Moses suggests that both “sides” prepare themselves overnight and in the morning offer incense to God, to see whom God favors. God accepts the offering from Aaron and the priests, and then the earth opens up and swallows Korach and his followers.

It’s easy for moderns to empathize with Korach. Maybe we too have chafed against leadership, religious or otherwise, that has seemed too top-down. The modern-day legal system under which we live says that every citizen is equal in the eyes of the law, and the ancient priestly system that placed Aaron and his sons at the top of the hierarchy may offend our democratic sensibilities.

Most of all, Korach’s cry — “all of the community are holy, and God is in their midst” — speaks to us on a spiritual level. Torah teaches that when we build a space in our lives for God, God dwells among us (or within us). Being a leader doesn’t make one closer to God, and any leader who thinks that it does is in need of doing some serious internal work.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

But this story isn’t as simple as it may initially seem. Korach is identified as a son of Levi — part of the “secondary” priestly caste in the ancient system that placed Kohanim (priests) at the top of the ladder, Levi’im (Levites, or secondary priests) beneath them, and Yisrael (ordinary Israelites) at the bottom. It’s possible that his rebellion wasn’t motivated by the kind of communitarian impulse that moderns might admire, but by the desire to depose Aaron and his sons so that Korach and his sons could be at the top of the hierarchy instead. Seen through that lens, Korach and his followers attempted a coup that would have replicated the same top-down use of power against which we want to think they are rebelling.

I’m also struck by the language the Torah uses to describe the incident: Korach and his followers “assemble against” Moses and Aaron. This isn’t a friendly conversation, a heart-to-heart about the direction the Israelites are taking in their wilderness wandering, or a question about leadership style and priorities. This is rebellion.

After the deaths of Korach and his men, there is further destruction. More of the community rebels, blaming Moses and Aaron for the deaths of Korach and his followers, and this new group of rebels is struck down by a plague. Aaron and Moses could be forgiven for washing their hands of this stiff-necked people, but instead they make offerings to ask God to end the plague.

The rebellion ends when God offers a peculiar instruction to Moses and Aaron. God tells them to collect the wooden staffs belonging to every tribal chief (including Aaron), to inscribe each chief’s name on his staff and to bring the pile of walking sticks into the Tent of Meeting. When they do so, Aaron’s staff sprouts flowers, and that miracle quiets the people’s grumblings. The people who rebelled have been purged from the community, and because of the flowering staff, those who remain are able to regain hope.

Torah teaches us in this portion that when people jockey for power as did Korach and his followers, damage is done to the entire community. Torah shows us a model for leadership in Moses and Aaron, who act in the best interests of the people they serve, even though the community has added insult to injury by blaming them for the damage experienced by those who attacked them. And Torah offers us a path to healing from this kind of communal division.

When ugly behaviors have rent a community asunder, Torah calls us to center ourselves in a place where we can access the flow of holiness. Torah calls us to ensure that the community can be a safe place for healing. And Torah calls us to open our hearts to the miraculous flowering-forth of new possibilities and community renewal that can unfold when we are safe, and our hearts are open, and we have trust in the One.