Commentary on Parashat Pekudei, Exodus 38:21-40:38, 12:1-20

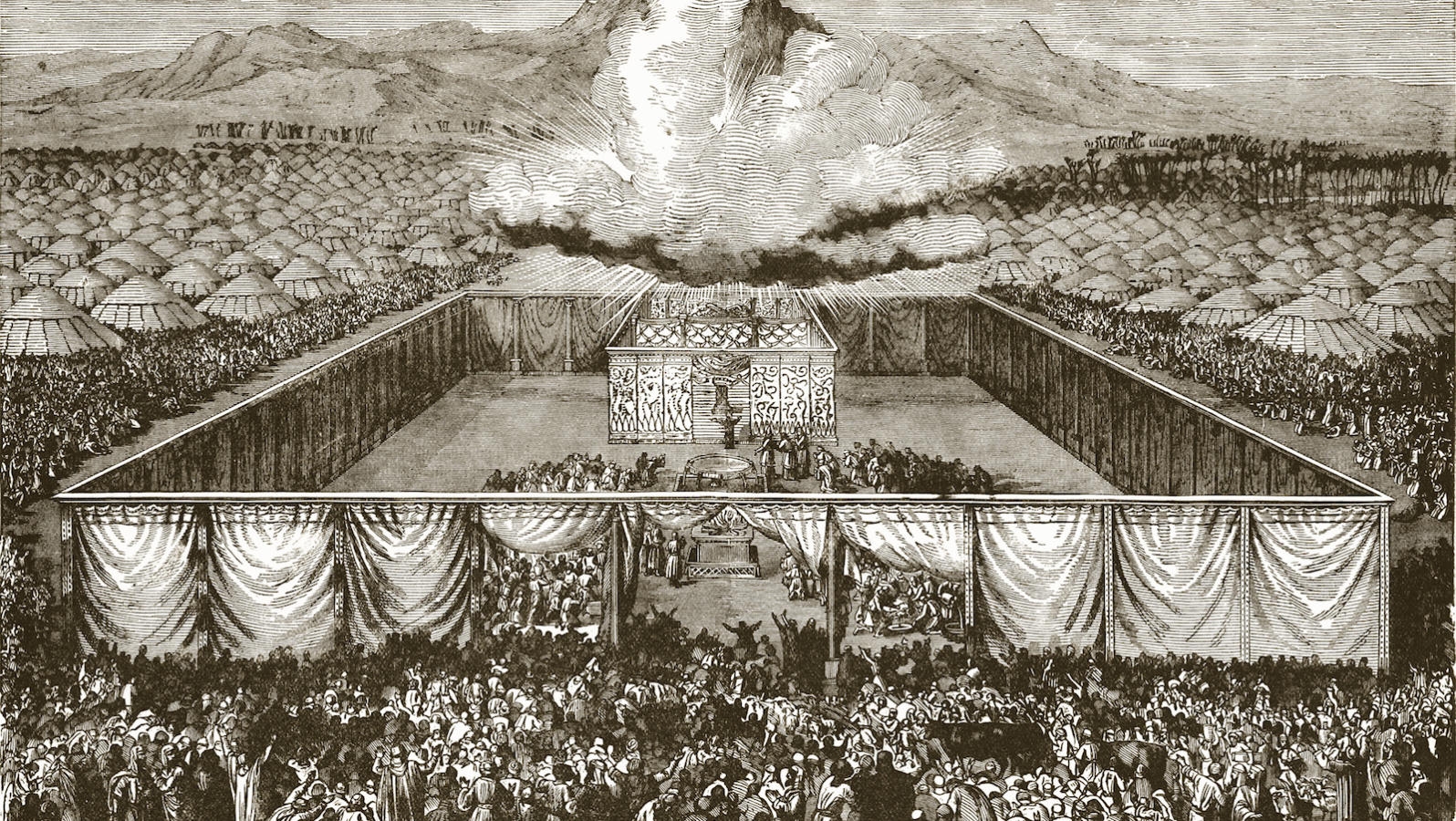

In Parashat Pekudei, the Tabernacle — which has been under construction for several parshiot — is finally completed and God’s Presence descends to dwell there, as a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.

The Tabernacle is many things: a place for God to dwell, a place for the Israelites to worship, a home for the sacred Ark of the Covenant. It is also, according to Midrash Tanchuma (a medieval collection of midrash), a microcosm of the world. Further, its construction parallels the creation of the world.

For example, the midrash explains, the laver, where the priests wash their hands and feet, is analogous to the gathering of waters on the third day of creation. The menorah, the seven-branched golden candelabra that lit the Temple, is like the heavenly lights created on the fourth day of creation. The many parallels in this midrash invite a larger comparison: Just as God created the world, humans created the Tabernacle. More generally: Just as God has the ability to create, humans also have the ability to create.

Through this midrash, we learn that the Tabernacle was a miniature world that ran precisely according to God’s commands. It was in this way a model world, one that could be perfected in a way that the larger world, at least by humans, cannot be. The Tabernacle was a place that one had to be pure in order to enter. It was a place that one went to atone for sins, to come closer — physically and spiritually — to God. The Tabernacle was a place where one came in line with God’s commands to be ethically, spiritually and physically pure. In short, it was the place where humans had the most control, the place where we could create an image of an ideal world.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

This midrash becomes even more striking when one considers which parallels between the Tabernacle and the world are not so exact. Water was created by God, but the water in the Tabernacle is not created, merely under the control of humans — a continuous creation, in a sense. God formed birds and beasts in the act of creation, but in the Temple animals were not created by humans, they were sacrificed by humans. And yet still these animals were of central importance in the Israelites’ imitation of God: Just as God has power over life and death, so do humans. And when humans must come face-to-face with animals they themselves have carefully reared without blemish, and end the lives of those animals and pour their blood on the altar, this must have been a stark reminder of their own vulnerability — God could do the same thing to us at any time. The high priest, too, is in some ways parallel to God, but also different: Aaron was only appointed to his position. A close examination of the imperfections in the metaphor reminds us that humans are not divine. While we can come close to accomplishing or imitating some of the things God can and has done, we are not the same.

The Torah tells us that when the Tabernacle was completed, Moses sanctified it, just as God did with the seventh day after creation. But the verse describing the completion of the Tabernacle (Ex. 39:43) indicates again the inherent difference between humans and God: Moses did exactly as God commanded and was subordinate to God, whereas God created the world in God’s own design and is subservient to no one.

The metaphor that the Tabernacle as a mirror of the world imparts to us is powerful and important: Humans have a great amount of power in the world, and yet we are all heart-breakingly vulnerable to forces beyond our control. Both halves of this equation are important, and we must ask: What do we do with such power? Do we make the world into its ideal form, as we did with the Tabernacle, or do we use our power to harm the world and those in it? Do we attempt to improve ourselves and build relationships with others? At the same time, we must remember we cannot do everything — we may improve the world, but we aren’t going to perfect it. That doesn’t exempt us from trying, as Rabbi Elazar says in Pirkei Avot (2:21): “It is not incumbent upon you to finish the task, yet you are not free to desist from it.”