The hope for the redemption of the Jewish people–the end of exile and the return to the Land of Israel–is a central component of Jewish religious belief. The transformation of this religious belief into a political ideology at the end of the 19th century led to the creation of the Zionist movement.

For Jews, the dominant issue of the day was the so-called “Jewish Problem,” the anti-Semitism and outsider status Jews faced in Europe. The Zionists perceived this “problem” as one that could only be solved by a Jewish national home. Early Zionism was divided into four major streams–religious, political, cultural, and labor-socialist. All except the first constitute the different types of secular Zionism.

Political Zionism

Most of us associate Theodor Herzl with the founding of the Zionist movement. This is true in that Herzl succeeded in bringing together under one organizational roof various Zionist groups; however, there was significant Zionist activity before Herzl came onto the scene.

More than 20 new Jewish settlements were established in Palestine between 1870 and 1897 (the year of the first Zionist Congress). These were built by various groups, most notably Hovevei Zion (“lovers of Zion”), a network of local Zionist groups in Eastern Europe. Hovevei Zion joined together secular and religious Jews who shared the goal of colonizing the Land of Israel and did so in a proactive and organized way that set a precedent for the future.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Leo Pinsker, a doctor from Odessa, became one of the leaders of Hovevei Zion. In reaction to growing anti-Semitism in Russia and the pogroms of 1881, he wrote an important pamphlet, “Auto-Emancipation” (1882), in which he said the Jewish people were a “nation long since dead.” The Jew, “a ghost,” was hated by all, cursed to live out the millennia along with anti-Semitism, which would continue as long as the Jew walked among the nations.

To Pinsker, the answer was what he called Auto-Emancipation: The Jewish people had to organize, revive itself as a nation, and remove itself to a new land. “We need nothing but a large piece of land for our poor brothers; a piece of land which shall remain our property, from which no foreign master can expel us,” he wrote. Pinsker did not believe that this land had to be the Land of Israel (though this was preferable), but first and foremost a refuge–granted by the nations of the world–that would save and rehabilitate the Jews.

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl, an assimilated Jew who lived in Vienna, independently came to similar conclusions, which he explained in his pamphlet “The Jewish State” (1895). Herzl, a well-known correspondent for an important Viennese newspaper, showed little interest in Jewish subjects until the early 1890s. His experiences with anti-Semitism, both in university and in later life, convinced him that “the world needs the Jewish State; therefore it will arise.”

Herzl set out a plan: The nations of the world should come together and grant the Jews their natural right to a state. He envisioned the creation of a Society of Jews that would be charged with the administration of the land that would be granted (hopefully Palestine, but the society would “take whatever it is given and whatever Jewish public opinion favors”). The Society would set up a Jewish Company that would liquidate Jewish property in the Diaspora and reinvest in building the new homeland. Herzl even discussed which professions should emigrate first and the kinds of buildings that should be erected.

In the first Zionist congress in 1897, Herzl championed his vision of a Jewish state, noting that if colonization efforts continued at the small rate they were moving, it would take “900 years” to gather all of the Jews to the land. At first, Herzl and the Zionist movement entertained the possibility of other lands (Argentina, Uganda), but from 1905, the only land considered by the Zionists was the Land of Israel.

To thinkers like Herzl and Pinsker the main stage was the political stage, with the ultimate goal being the creation of Jewish sovereignty in a land granted by the nations, followed by mass Jewish emigration. Notions of a Jewish social and cultural revolution were not central in their writings.

Cultural Zionism

Not everyone applauded Herzl as they listened to his speeches during the first Zionist Congress in 1897 in Basle.

Asher Zvi Ginsberg–better known as Ahad Ha-am (“One of the Nation”) and also known as the “Agnostic Rabbi”–was horrified by Herzl’s answer to the Jewish Problem. According to Ahad Ha-am, the redemption of the Jewish people would come only from a Jewish cultural and spiritual revival, not the creation of a political state.

Ahad Ha-am did not believe that the “Ingathering of the Exiles” should be the goal of Zionism. While a politically sovereign state could be a possible outcome of the colonization efforts, it could not supercede the spiritual and cultural revival which must be at the center of the effort. The revival of Hebrew language, literature, art, music, and Jewish study within an organic, natural Jewish environment in the original homeland were not dependent on Jewish sovereignty, but on a small, talented, and committed core of pioneers.

Ahad Ha-am wanted “not merely a State of Jews but a really Jewish state,” which would be the center of the worldwide Jewish revival, from which the spirit of Judaism would “radiate to the great circumference, to all the communities of the Diaspora.”

Although he represented a minority in the movement and was often a gadfly, he remained highly respected. When he moved to Tel Aviv (where he died in 1927), the street upon which he lived was closed during his naptime, and on Friday nights, many residents of Tel Aviv would gather there for the “Oneg Shabbat” celebration, a secular observance of the Sabbath Eve.

Labor-Socialist Zionism

In many ways, the labor-socialist Zionists succeeded in synthesizing the political and cultural streams through their ambitious colonization projects, social vision, and ideology of cultural and social revolution.

Many Jewish Marxists were committed to Zionism and the return to the Land of Israel, but they faced an inherent conflict between communism’s internationalist focus and Zionism’s nationalist focus. Jewish Marxists, therefore, worked to reformulate the Communist Manifesto to fit into a Zionist context. The most important of these thinkers was Ber Borochov, who interpreted the Jewish Problem in class terms and held that “the emancipation of the Jewish people either will be brought about by Jewish labor, or will not be attained at all” (“Our Platform” 1906).

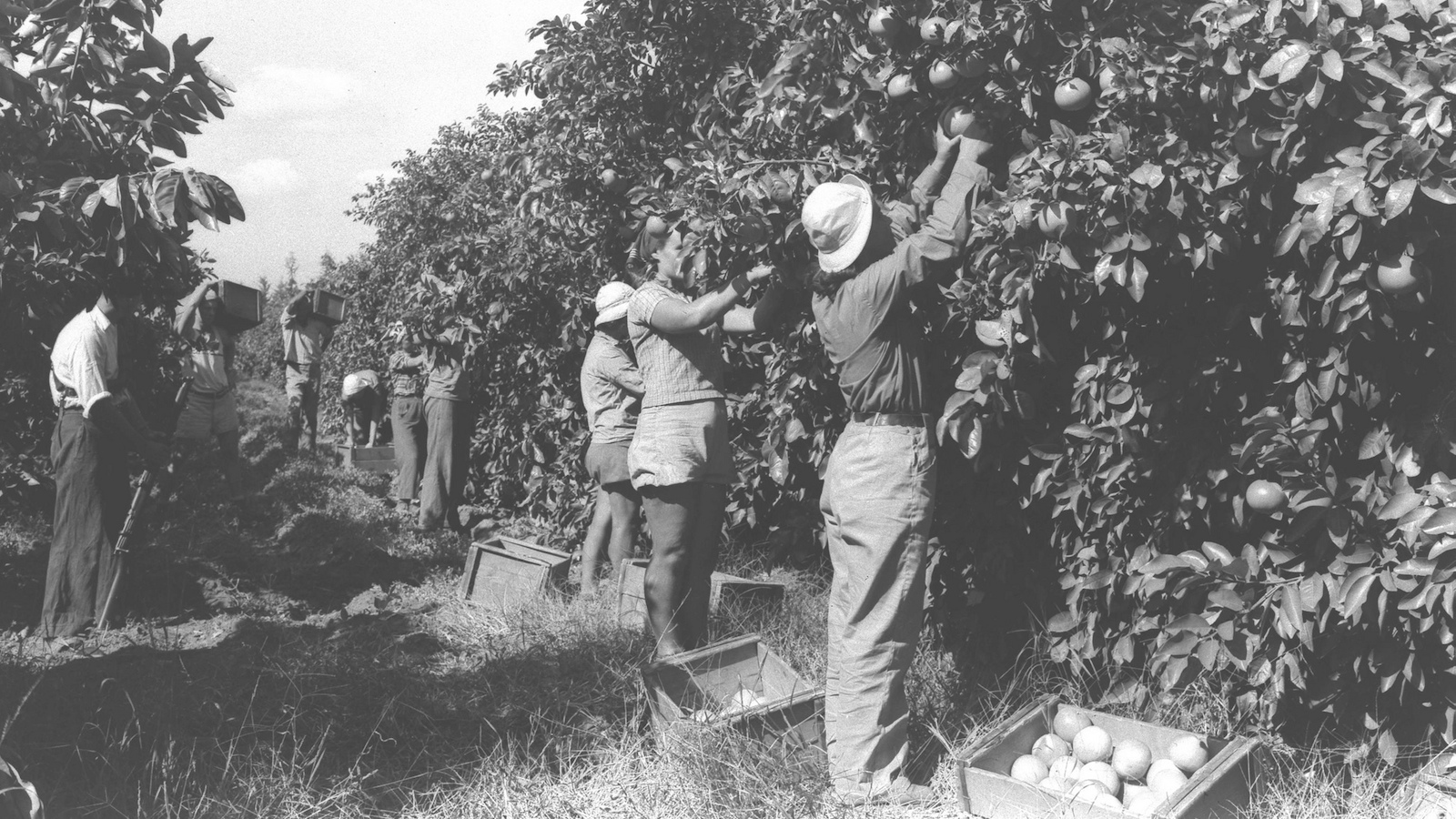

According to Borochov, immigration to the Land of Israel, if planned and executed properly, would transform the Jewish people from a petty bourgeoisie society into a healthy society, based on Jewish workers who would forgo their shops and clerkships for the fields and factories of the new Jewish homeland. Marxist-Zionist ideology, stemming from Borochov’s formulations, was the basis of the kibbutz movement (which built communal villages and farms) and was a dominant force in Israeli politics for many years.

An important leader of the socialist Zionist movement who acted upon Borochov’s ideals was Berl Katznelson. When he came to the Land of Israel in 1909 from Russia, Katznelson worked as a farm laborer and eventually became the leader of the socialist Zionists, until his death in 1944.

As the founder and editor of the labor-socialist newspaper, Davar, the entire cultural and ideological program of the workers in the Land of Israel were under his influence. His love of Jewish culture, the Hebrew language, and commitment to social justice are apparent in all of his writings. Katznelson’s greatest contribution was his call for contemporary Jews to reinterpret ancient Jewish values for the modern secular worker. He urged his fellow revolutionaries to find ways to integrate newly interpreted Jewish values and culture into their lives and not relate to the Zionist revolution as one that “destroys the old world entirely.”

An example of how he used his influence: In 1936 Katznelson wrote an article in which he criticized his party’s youth movement for holding a celebratory campfire on Tisha B’Av, the day for mourning the destruction of Jerusalem. He urged the youth and their leaders to find innovative and meaningful ways to adapt the old traditions to the new reality, reinterpreting traditional Judaism for the modern Hebrew worker (beyond campfires and sing-alongs). In modern Israel, the words of Katznelson remain relevant for many secular Jews who struggle to find ways to connect to Judaism outside the framework of religious beliefs and traditional observance.

Each of these secular ideologies brought a unique worldview that enriched Zionist discourse and brought fresh ideas into the conversation. Often these ideas clashed, sometimes they found common ground. The dynamism and diversity of Israel is rooted in the rich ideological soil from which the state grew.