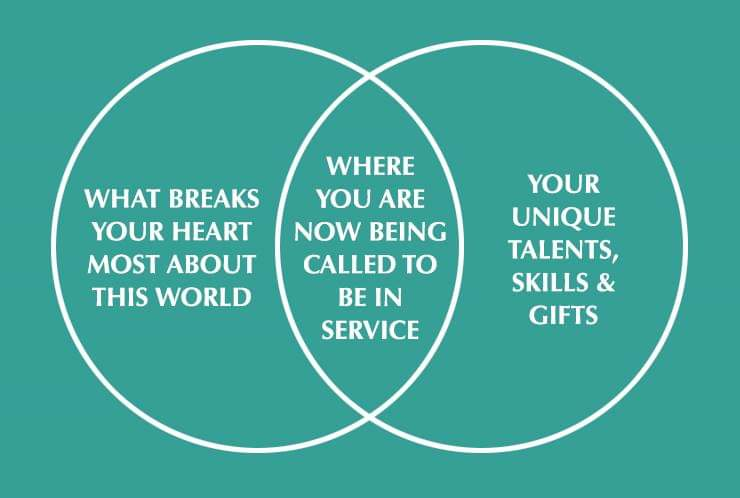

Aleinu is a prayer recited at the end of services, as we are about to depart from sacred community. It is like a pep-rally to get us motivated and ready to go back out into the world to serve. The prayer is composed of two stanzas, which are well illustrated by the Venn diagram below.

The first stanza can be controversial, but it doesn’t have to be. One of the problematic lines thanks God she-lo assanu k’goyei ha’aratzot — “who has not made us like the nations of the world.” This is a declaration that we stand for the mission of Judaism, which is essentially to be a “God wrestler” (one possible translation of the word Israel).

As Jews, we struggle to understand what God is and what God desires for our world. This struggle is what gives meaning to our lives. This is not to say that other religions or groups are not also God wrestlers, but Jews wrestle in a unique way. We wrestle in Hebrew, on Shabbat, on our holidays. We wrestle through Torah and our rabbis. We wrestle in a different way with the State of Israel. And we are grateful for this, because it gives us a unique place in the world and a unique worldview, not to the detriment of others.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

A second controversial line reads: She-lo sam chel’keinu ka-hem — “who has not placed our portion like theirs.” Each and every one of us has a set of talents, experiences and blessings that are uniquely ours. Our task is to figure out how we use the tools that we are given. Aleinu allows us to connect our unique being back to the very nature of creation, as it says in the prayer’s opening line, Aleinu le-shabei-ach la-adon ha-kol, la-tet gedulah l’yotzer bereshit — “It is our obligation to praise the Master of it all, to ascribe greatness to the author of creation.” For all of these skills and talents that we possess, we are obligated to praise. But how?

The second stanza answers that question. All that we have to do is le-taken olam b’malchut shaddai — to repair the world (tikkun olam) through malchut shaddai (we’ll translate this later). Many people believe that tikkun olam is simply about fixing the world and doing good. But it is tied to a kabbalistic view of creation that imagines the creator pouring itself into the world. Along the way, the earthly vessels were unable to contain the all-ness of the divine and they shattered and spread throughout our world.

These shards can be found in all places, even places that appear at first glance to be dank and devoid of holiness. In these places, we are called on to search out those shards of the original divine vessel which held the all-ness of the One and lift up the sparks, the residue of holiness left from that original break.

So when we consider what most breaks our hearts in the world, we can think about the places where the sparks are most hidden. When we use our unique talents and blessings to effect change where we see a great need, we are truly praising God. Aleinu reminds us of our abilities, empowers us to step into difficult places and to find God there. The prayer tells us that by acting with godly purpose in those places, we are doing tikkun olam, strengthening the world to hold more divinity.

What about malchut shaddai? Most simply, it is translated as the kingdom of God. But the essence of malchut shaddai is the interconnectedness of all life. It’s the flow that exists between all things, where each element in creation both provides for and takes from the whole. So we are charged with doing tikkun olam through our unique gifts because we are given these gifts for no other reason than to do tikkun olam. We have what someone else lacks. We need what someone else can give us. We are all connected, so we owe it to the author of creation to reinvest in the system, to manifest the plan.

Aleinu concludes with a vision of sacred unity, taken from Zecharia 14:9: Bayom ha-hu yih-yeh Adonai echad u’shemo echad — “On that day, God will be one and His name will be one.” This vision sees a world where we all come to prioritize the connections between us, to serve in a way that benefits the greater good and others even if it does not appear to immediately benefit us.

On that day, God’s name will be one. The service of all religions, all who wrestle with God, will then be complete and all will come to know that we’ve truly been serving the same purpose. We will then all be able to call God by the true name, which we will discover on that day. But to bring us to that day, we must first each discover where we are being called into service.

Rabbi Tiferet Berenbaum received rabbinic ordination and a master’s degree in Jewish education from Hebrew College in Boston. She is the spiritual leader of Temple Har Zion in Mt. Holly, New Jersey.