Anti-Semitism is a modern ideology that has drawn on images of Jews that were formed over centuries. This is well-documented in Christian societies. But today, anti-Semitism is much more prevalent in the Muslim world.

The Anti-Defamation League’s Global100, an index of anti-Semitic sentiment worldwide, has shown that the overwhelming majority in Muslim countries endorse anti-Semitic statements. The Pew Research Center has also found that negative attitudes toward Jews are the norm rather than the exception in many Muslim countries. The vast majority of people in Egypt, Jordan, and Pakistan attest to having a “very unfavorable view” of Jews. Anti-Semitism has become so widespread in the Muslim world that the very word “Jew” is now a commonly used insult. This is less true among Muslims in the United States and Europe, but even Muslims living in the West demonstrate higher levels of anti-Semitism than their their non-Muslim counterparts.

While it might be tempting to say that these beliefs represent an eternal hatred of Jews among Muslims, or that Islam or Israel is to blame, the truth is that Muslims and Jews have enjoyed positive relations throughout history, including today. There are many positive examples of Muslim-Jewish coexistence in medieval Spain, despite the institutional discrimination against non-Muslims at the time, and fascinating stories of rescue of Jews by Muslim Albanians during the Holocaust. Jews and Muslims have made common cause on contemporary issues of concern to both communities, including ritual slaughter and the right to circumcision. And the recent moves toward normal diplomatic ties between Israel and several Arab countries are proof that the essentializing view of an eternal enmity between Jews and Muslims is false.

But various historical and political developments have had a negative impact on how Jews are seen today in the Muslim world.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Siimilarly to Christianity, some sacred Muslim texts invite hostility against Jews, although positive statements about Jews can also be found in them. The Koran and the Hadith (a collection of sayings attributed to the Prophet Mohammad) can be interpreted in ways that suggest Muslims and Jews are enemies, that Jews will be killed at the end of times, that Jews falsified scripture, and that Jews tried to kill Mohammed. “You [Prophet] are sure to find that the most hostile to the believers are the Jews and those who associate other deities with God,” reads one verse from the 2008 translation of the Koran by Islamic scholar Abdel Haleem.

The fact that Mohammed killed and enslaved the Jews in Medina has also been used to incite violence against Jews, although there were also positive encounters between Mohammed and Jewish tribes. Jews and Christians were mostly tolerated in premodern Islamic societies, but they were also targets of institutional discrimination and treated with contempt. Jews were subjected to special taxes, segregation, and in some cases even pogroms, such as in Fez in 1033 or Granada in 1066. Similar to Christianity, this produced a rich reservoir of anti-Jewish stereotypes.

With the arrival of European colonizers and missionaries in the Middle East in the 19th century, Christian anti-Semitic themes were introduced to the region. One of the most infamous examples is the 1840 Damascus blood libel, in which Capuchin monks accused the local Jewish community of murdering a fellow friar and his Muslim servant in order to use their blood for Passover rituals. The accusers had the support of the French consul and local Muslims participated in subsequent riots against the local Jewish community.

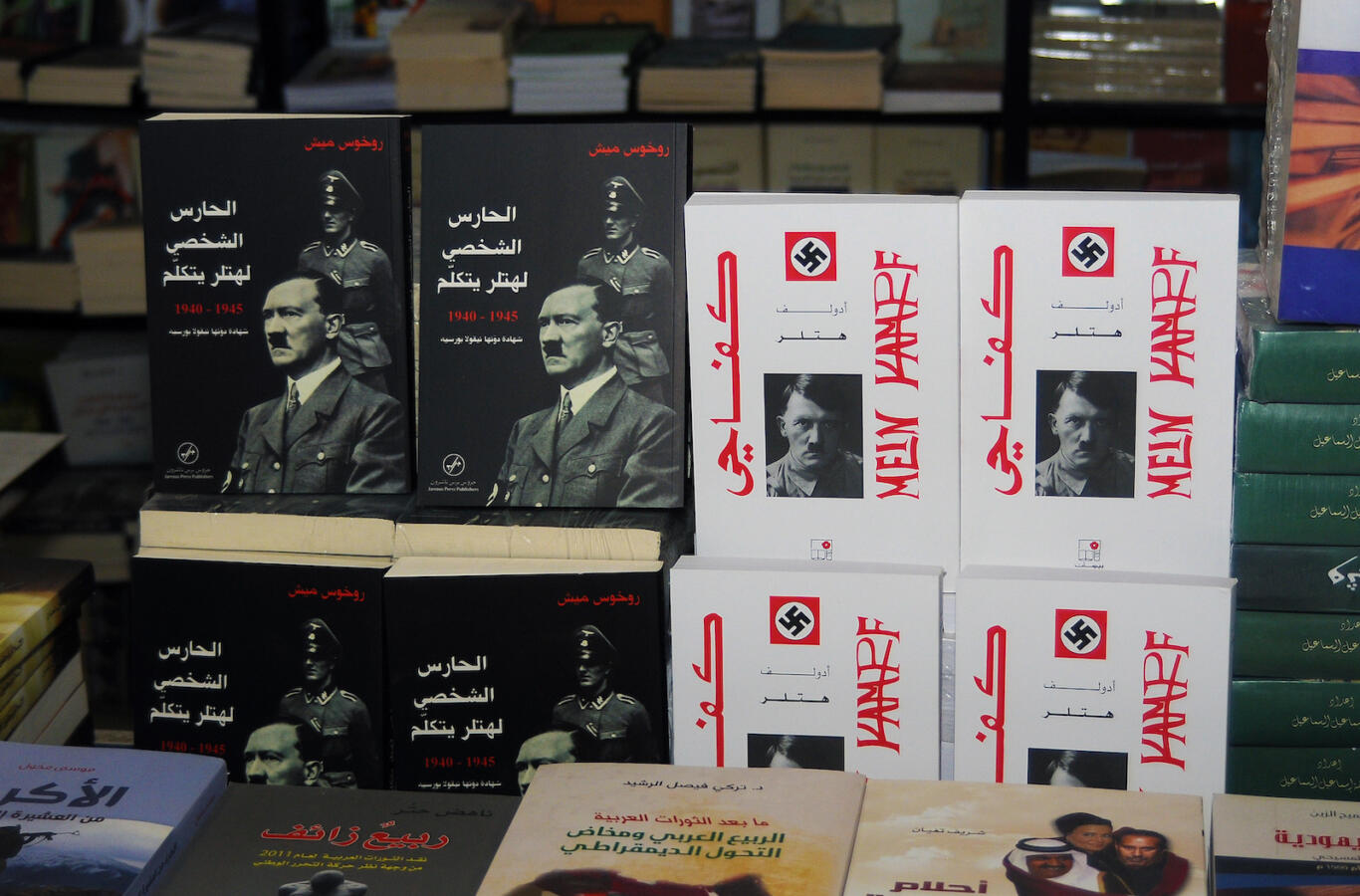

The blood libel and other tropes that came from Christian countries took some time to take hold among Muslims, but they eventually became widespread. In 1983, Mustafa Tlas, Syria’s longtime defense minister until 2004, published a version of the blood libel entitled “The Matzo of Zion.” Similar books are widely read today in the Arab world.

In the early 20th century, the growing movement of political Islam saw Christians and Jews as waging war against Muslims and held the Jews responsible for the alleged decay and westernization of Islamic societies. Sayyid Qutb, member of the Muslim Brotherhood and one of the movement’s most influential thinkers, wrote a widely disseminated pamphlet entitled “Our Struggle with the Jews,” in which he drew parallels between contemporary developments and Mohammed’s struggle with the Jews. “The Jews also conspired against Islam by inciting its enemies against it throughout the world … Jews as Jews were by nature determined to fight Allah’s Truth and sow corruption and confusion. Judaism was by nature defective and corrupted Truth; while true Muslims and true Islam were by nature the mirror opposites of Jews and Judaism,” he wrote. (Translation by Ronald Nettler)

Qutb also saw the return of Jews to Palestine as an evil that demanded punishment. “Let Allah bring down upon the Jews people who will mete out to them the worst kind of punishment, as a confirmation of His unequivocal promise: ‘If you return, then We return,’” he wrote. Qutb’s writings inspired Islamists around the world, from Jamaat-e-Islami in south Asia to Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini. The Muslim Brotherhood is a global network today, still disseminating such ideas. One of their main spiritual leaders today, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, is a preacher on Al Jazeera and heads the European Council for Fatwa and Research. He believes that Hitler was sent as a devine punishment for the Jews and advocates for another Holocaust. In 2009, he stated that, “God willing, the next time this punishment will be inflicted by the hand of the Faithful,” by which he means Muslims. Radical jihadist groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS have embraced similar ideas.

The rise of Nazism in the 1930s also commanded a following among Arabs. Some Arab nationalist movements in the 1930s and 1940s were modeled on the German national socialist movement. The Nazis also exploited Arab hostility toward the British and French imperial forces and widely disseminated radio propaganda in close cooperation with Islamist leaders, most notably the mufti of Jerusalem, Amin Al-Husseini. This propaganda fused traditional Islamic anti-Jewish beliefs with conspiratorial imagery of “world Jewry.” Yet even before his collaboration with the Nazis, Al-Husseini introduced the infamous lie that Jews wanted to tear down the Al Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, a claim that has been repeatedly used as evidence that the Jews were waging a war against Islam and which still leads to violence against Jews.

After World War II, Nazism was not as delegitimized in the Muslim world as it was in Europe. Prominent Nazis, such as Ludwig Heiden (alias Louis al-Hajj) and Johann von Leers (alias Omar Amin) continued their propaganda activities in Arab countries after the war. Alois Brunner, an SS officer who served as Adolf Eichmann’s assistant, advised the Syrian regime on torture. In 1953, Anwar el-Sadat, who would later become the Egyptian president, wrote a tribute to Hitler. Even today, Hitler remains a popular figure and “Mein Kampf” a bestseller in Turkey and other countries.

After the war, pan-Arabism, a movement that sought to unify the Arab world under one government, emerged as a major political force, combining elements of Arab supremacist ideology with resistance to European imperialism. It too embraced elements of Nazism. Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of Egypt from 1954 until 1970 and a leading pan-Arabist, was a member of a pro-Nazi movement in the 1940s and protected Nazi officials after the war. Nasser also supported the dissemination of anti-Semitic propaganda in Arabic, including the notorious forgery known as “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

A central element of Arab anti-imperialist ideology was the portrayal of Israel as the principal obstacle to Arab unity. Anti-Zionist rhetoric, enforced by close cooperation with the Soviet Union, which ran anti-Zionist campaigns for its own purposes beginning in the 1950s, mostly failed to distinguish between demonizing Israel and demonizing Jews. Even today, Syrian textbooks present the alleged Zionist control of the global media as a fact. The Holocaust, on the other hand, is not mentioned in history textbooks. Hitler is portrayed as a strong leader, defending Germany against the Jews.

Pan-Arab nationalists used anti-Zionist rhetoric that scarely masked their anti-Semitic worldviews. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, who bombed Israel repeatedly during the Gulf War in 1991 and designated the “Zionist entity” as his country’s worst enemy, regularly conflated Jews, Zionists and Israelis. “[W]e should reflect on all that we were able to learn from ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,’ and reflect on the nature of discussions that took place,” Hussein told Ba’ath Party members in one of the thousands of hours of audio recordings captured by the Americans after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. “We should identify the methods adopted by these hostile Zionist forces; we already know their objectives. I do not believe that there was any falsification with regard to those Zionist objectives.”

Such ideas of Zionism, Jews, and Israel have deeply penetrated Arab societies. But there are also some recent signs of change. Ties between Israel and some Arab countries, such as the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco, have warmed with signing of agreements aimed at normalizing relations. Arab countries have also grown interested in the history of their Jewish communities, who were often chased away in the years following the establishment of the State of Israel. The ideological front of demonizing Jews, Zionists, and Israel alike may be crumbling.