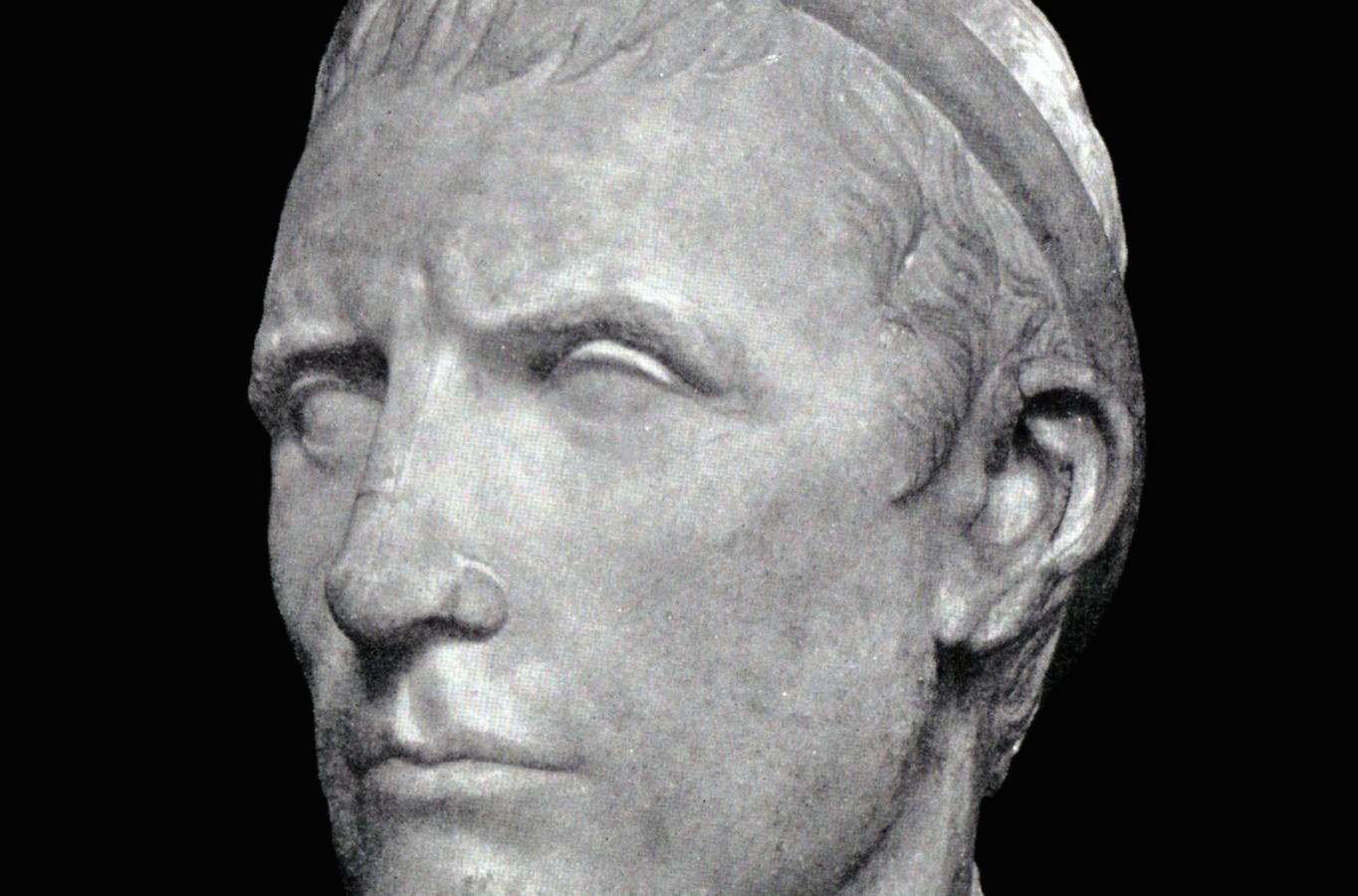

In 175 BCE, amid this social-political unrest, a new ruler, Antiochus IV, ascended to the throne of Greco-Syria. As did many rulers, he appended the title Epiphanes (“God Manifest”) to his name; but many people referred to him instead as Antiochus Epimames (“The Madman”).

Immediately upon assuming power, he decided to pursue the conquest of Egypt, which no other Seleucid king had been able to accomplish. The Romans were advancing eastward and expanding their empire. If Antiochus could conquer and annex Egypt, his kingdom’s size and power would be greatly increased and the Romans might be resisted.

But before doing so, he would have to stabilize his own country and consolidate political support by uniting the disparate cultural, social, and religious elements. Under Alexander the Great, hellenization had been a movement that still allowed room for cultural variation; under Antiochus, hellenization was intended to take a big step further and become the agent of cultural totalitarianism.

Antiochus’ Relationship with Jews

The Jews were clearly targets of Antiochus’s strategy of Hellenization. He understood that to ultimately succeed in Egypt, he would need to disrupt the influence of the Jews within his own territories. He decided to tackle the priesthood in Jerusalem by replacing Onias the Third, the latest Kohen Gadol (high priest), with Onias’s brother Joshua, who was loyal to the Greeks. Joshua became High Priest and immediately changed his name to Jason.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

To a certain extent, Antiochus’s plan worked. Jason submitted to the king’s will and helped implement the new totalitarian doctrine. Jerusalem became a little version of Antioch, replete with a gymnasium where the Jewish Kohanim often played Greek sports in the nude. Meanwhile, King Antiochus had access to the Temple treasury to help fund his military campaign to conquer Egypt.

All these activities fueled the restless anger of the pious Jewish peasants, who became even more enraged when Antiochus allowed Menelaus, a Tobiad, to purchase the position of Kohen Gadol. They were incensed that this sacred position, for which Menelaus had outbid Jason, was for sale at all. But to make matters worse, Tobiads were not even descendants of Aaron, who was the brother of Moses and the traditional ancestor of all Kohanim.

As a condition of his appointment, Menelaus had promised he would increase the tax revenue. When he failed to do so, he was summoned to appear before the king. While away, Menalaus left his brother Lysimachus as High Priest in his stead. Lysimachus proceeded to rob the Temple of many of its sacred vessels, an action that led to riots in the streets, during which the supporters of Jason (even knowing all his faults) battled the supporters of Menelaus.

Expansion in the Middle East

Meanwhile, after a decisive battle in 169-8 BCE, Antiochus was on the brink of annexing Egypt to Syria. The Roman army, however, was moving victoriously eastward. With its own sights set upon Egypt, Rome warned Antiochus not to expand his kingdom in that direction. Antiochus was not powerful enough to defy the mighty Roman Empire; and finding his ambitions for conquest thwarted, he would become even more aggressive toward the people he already ruled.

While Antiochus was away, Jason had managed to retake Jerusalem from Menelaus — a victory based on the rumor that Antiochus was dead. But he was not able to seize control of the government, and he was forced to flee. Antiochus, furious with the rebellion, returned to Jerusalem, slaughtered thousands of people, and reinstalled Menelaus. Once Antiochus departed and heard that a second rebellion had broken out, he outlawed Judaism. Among the now-forbidden practices were the rite of circumcision, the study of Torah, and the keeping of kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).

In the Jews’s Holy Temple, he placed a statue of Zeus — the god he believed was manifest in his own royal being — and sacrificed swine on the altar. He stripped the Temple of its sacred vessels, including the seven-branched golden menorah, and stole the silver and gold coin.

Reprinted with permission from Celebrating the Jewish Year: The Winter Holidays, published by Jewish Publication Society.

Hanukkah

Pronounced: KHAH-nuh-kah, also ha-new-KAH, an eight-day festival commemorating the Maccabees' victory over the Greeks and subsequent rededication of the temple. Falls in the Hebrew month of Kislev, which usually corresponds with December.