From The JPS Commentary: Leviticus. Reprinted with permission from the Jewish Publication Society.

Holiness is difficult to define or to describe; it is a mysterious quality. Of what does holiness consist? In the simplest terms, the “holy” is different from the profane or the ordinary. It is “other,” as the phenomenologists define it. The “holy” is also powerful or numinous. The presence of holiness may inspire awe, or strike fear, evoke amazement. The holy may be perceived as dangerous, yet it is urgently desired because it affords blessing, power, and protection.

Holiness & Otherness

The Sifra, a rabbinic midrash, conveys the concept of “otherness” in its comment to Leviticus 19:2: “‘You shall be holy’–You shall be distinct (perushim tiheyu),”meaningthat the people of Israel, in becoming a holy nation, must preserve its distinctiveness from other peoples. It must pursue a way of life different from that practiced by other peoples. This objective is epitomized in the statement of Exodus 19:6: “you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation (goy kadosh).” (A better rendering might be: “You shall be My Kingdom of priests and My holy nation.”) This statement also conveys the idea, basic to biblical religion, that holiness cannot be achieved by individuals alone, no matter how elevated, pure, or righteous. It can be realized only through the life of the community, acting together.

The words of Leviticus 19:2 pose a serious theological problem, especially the second part of the statement: “For I, the LORD your God, am holy.” Does this mean that holiness is part of the nature of God? Does it mean that holiness originates from Him? In the Jewish tradition, the predominant view has been that this statement was not intended to describe God’s essential nature, but, rather, His manifest, or “active,” attributes. To say that God is “holy” is similar to saying that He is great, powerful, merciful, just, wise, and so forth. These attributes are associated with God on the basis of His observable actions: the ways in which He relates to man and to the universe. The statement that God is holy means, in effect, that He acts in holy ways: He is just and righteous. Although this interpretation derives from later Jewish tradition, it seems to approximate both the priestly and the prophetic biblical conceptions of holiness.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Interaction between God & Man

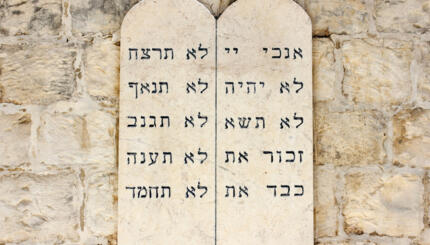

In biblical literature there is a curious interaction between the human and the divine with respect to holiness. Thus, in Exodus 20:8, the Israelites are commanded to sanctify the Sabbath and to make it holy; and yet verse 11 of the same commandment states that it was God who declared the Sabbath day holy. Similarly, God declared that Israel had been selected to become His holy people; but this declaration was hardly sufficient to make Israel holy. In order to achieve a holiness of the kind associated with God and His acts, Israel would have to observe His laws and commandments. The way to holiness, in other words, was for Israelites, individually and collectively, to emulate God’s attributes. In theological terms this principle is known as imitatio dei, “the imitation of God.” The same interaction is evident, therefore, in the commandment to sanctify the Sabbath, with God and the Israelite people acting in tandem so as to realize the holiness of this occasion. God shows the way and Israel follows.

The biblical term for holiness is kodesb. Though the noun is abstract, it is likely that the perception of holiness was not thoroughly abstract. In fact, kodesh had several meanings, including “sacred place, sanctuary, sacred offering.” In addition, in certain syntactic positions, Hebrew nouns function as adjectives. Hebrew shem kodsbo, for example, does not mean “the name of His holiness” but, rather, “His holy name.” This leads to the conclusion that in the biblical conception holiness is not so much an idea as it is a quality, identified both with what is real and perceptible on earth and with God. Indeed, the only context in which a somewhat abstract notion of “holiness” is expressed relates to God’s holiness. God is said to swear by His holiness, just as He swears by His life, His faithfulness, and His power. When speaking of God, it is recognized that holiness is inextricable from His Being; it is a constant, divine attribute.

Peoplehood & Ethics

The overall content of Leviticus 19, with its diverse categories of laws and commandments, outlines what the Israelites must do in order to become a holy people. It includes many matters of religious concern, as we understand the term: proper worship, observance of the Sabbath, and also the avoidance of actions that are taboo, such as mixed planting and consumption of fruit from trees during the first three years after planting. What is less expected in ritual legislation is the emphasis on human relations: respect for parents, concern for the poor and the stranger, prompt payment of wages, justice in all dealings, and honest conduct of business. Even proper attitudes toward others are commanded.

In this latter respect, Leviticus 19 accords with prophetic attitudes indicating that the priesthood was highly receptive to the social message of the Israelite prophets. Holiness, an essentially cultic concept, could not be achieved through purity and proper worship alone; it had an important place in the realm of societal experience. Like the Ten Commandments and other major statements on the duties of man toward God, this chapter exemplifies the heightened ethical concern characteristic of ancient Israel.

Holiness, as a quality, knows no boundaries of religion or culture. Very often, the reactions it generates are perceived by all, regardless of what they believe. Similarly, places and objects as well as persons considered to be holy by one group may be perceived in the same way by those of other groups. There is something generic about holiness, because all humans share many of the same hopes and fears, and the need for health and well-being. A site regarded as holy by pagans might continue to be regarded as such by monotheists; indeed, some of the most important sacred sites in ancient Israel are known to have had a prior history of sanctity in Canaanite times, although the Bible ignores the pagan antecedents and explains their holiness solely in terms of Israelite history and belief.

The Gulf Between the Sacred & Profane

Despite many differences between Israelite monotheism and the other religions of the ancient Near East, the processes through which holiness was attributed to persons, places, objects, and special times did not differ fundamentally. Through ritual, prayer, and formal declaration sanctification took effect. In biblical Hebrew, these processes are usually expressed by forms of the verb k-d-sb, especially the Piel stem kiddesh, “to devote, sanctify, declare holy.”

The gulf between the sacred and the profane was not meant to be permanent. The command to achieve holiness, to become holy, envisions a time when life would be consecrated in its fullness and when all nations would worship God in holiness. What began as a process of separating the sacred from the profane was to end as the unification of human experience, the harmonizing of man with his universe, and of man with God.