Commentary on Parashat Bo, Exodus 10:1-13:16

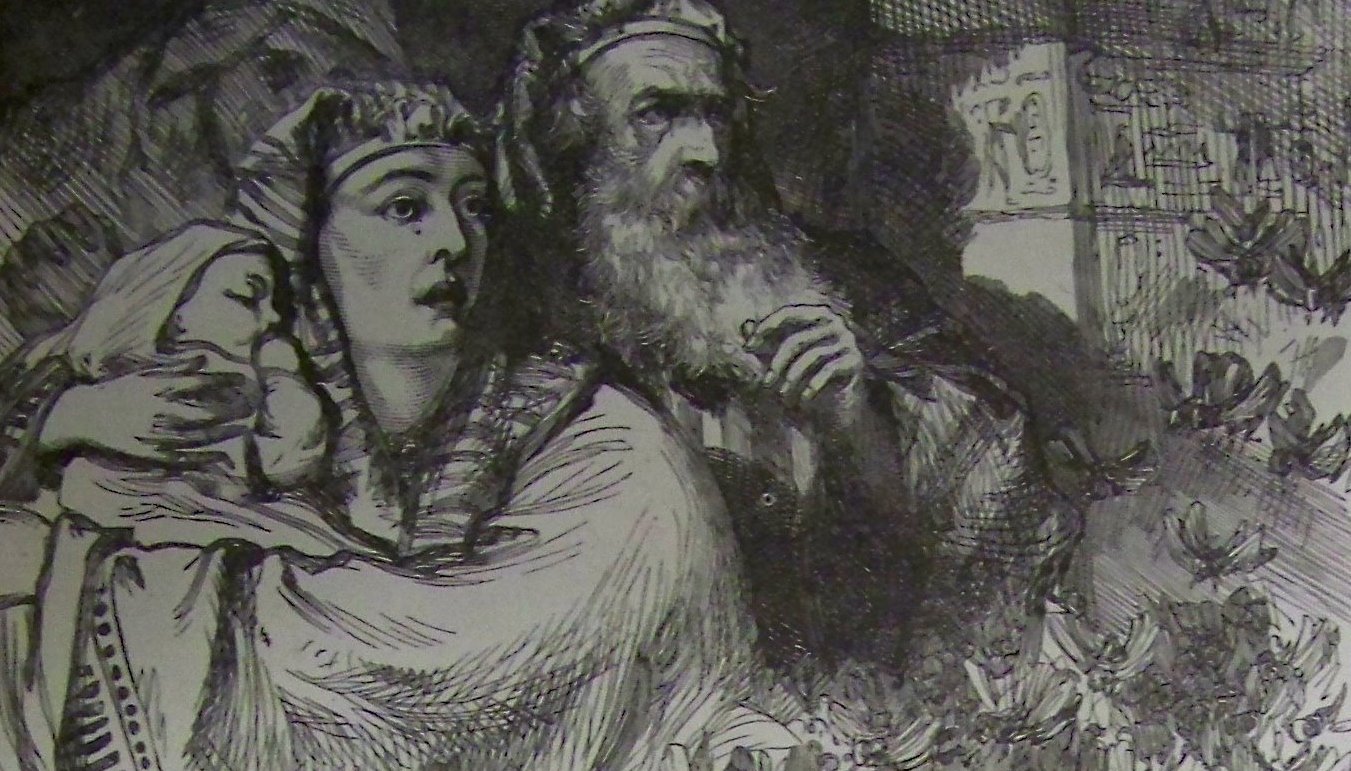

The dramatic contest of wills between God and Pharaoh is coming to a climax: The plagues upon Egypt become steadily more punitive, culminating with the death of the firstborn. Before the final plague, Moses and Aaron are given instructions by God to make a sacrifice, and to place the blood on the doorposts of the Israelite houses. Further instructions are given to eat unleavened bread and bitter herbs; this becomes the source of our Passover traditions. The firstborn of the Egyptians are struck dead; this is the final blow to Pharaoh, who sends the entire Israelite people in the middle of the night. Commandments concerning Passover and the sanctification of the firstborn are given as a remembrance of the Exodus.

In Focus

“Pharaoh called to Moses and said: ‘Go, worship God! Only your flocks and your herds will remain; your little ones will go with you.'” (Exodus 10:24)

Pshat

Pharaoh is stubborn and will not admit total defeat, even after nine afflictions upon his land and people. After the “plague” of darkness, he grudgingly allows the Israelites to leave Egypt; however, he wants them to leave their cattle behind, perhaps as the price of their freedom. Moses won’t hear of it, and tells Pharaoh that they need the cattle to make sacrifices to God out in the wilderness. Pharaoh’s heart is hardened once again, and he does not agree to Moses’s demands.

Drash

The exchange between Moses and Pharaoh at the end of chapter 10 is, on the simplest level, a battle of wills between political opponents, each trying to get the best deal for his side. Not unlike other famous negotiations in the Middle East, the two parties don’t trust each other, and each tries to give up as little as he can to the other.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The Hasidic master Rabbi from Pshi’scha, also known as the Yehudi HaKadosh (The Holy Jew), proposes a reading of the story far removed from the realm of political revolutions. The Yehudi imagines Pharaoh challenging Moses over his understanding of spirituality in worship:

Pharaoh said: “It is possible to worship God [only] in thought and in feeling. So if, in truth, you really desire to worship God–what do you need your flocks and herds for? ‘Go, worship God’–with an upright heart and pure intentions, and you won’t need to make any physical offerings, so ‘only your flocks and herds will remain.'”

Moses answered him: “Intentions alone, without any actions connected to them, aren’t important, aren’t anything! The main thing is real action, and thus intentions depend on actions and are deepened through them. Therefore, ‘our cattle will also go with us,’ (v. 26) because ‘we will take from them to worship our God.’”

From actions one is aroused to worship God with great feeling and to embrace the Divine. (Source: Itturei Torah, translation mine.)

Clearly, the Yehudi doesn’t think that Pharaoh was all that concerned with the Israelite’s spirituality — this is a parable about contemporary concerns. I understand the Yehudi to be addressing those people who want a purely internal spirituality, going deep inside themselves, spurning the physical world. The Yehudi, speaking through the character of Moses, seems to be suggesting that the proper way to deepen one’s inner life is to align it with your physicality, your embodied being.

An example that comes to mind is ritual action, something often derided by those who seek a purely internal, detached kind of spirituality. (Think of the negative connotations of the word “ritualistic.”) A simple ritual is making a blessing before eating, which can help bring us to feelings of awe and gratitude.

One might think that the best thing is to go directly to the proper feelings, and bypass the ritual, but I think it doesn’t really work that way. The action of the blessing can bring us to a depth of emotion and spiritual understanding unreachable by thought alone; sometimes we don’t even understand, on a spiritual level, what the ritual is all about until after we’ve done it many times.

I think I’ve quoted before one of my favorite teachings from another tradition: “It’s easier to act your way into right thinking than think your way into right acting.” Of course, a certain amount of intellectual preparation is crucial for Jewish practice, but I think the Yehudi reminds us that religious growth can’t happen only “from the neck up.” It happens when we bring physical and spiritual together, when we bring our whole being into the quest, when our actions in the social and religious realms become entirely aligned with our higher goals.

Provided by KOLEL–The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning, which is affiliated with Canada’s Reform movement.