Cantillation (from the Latin cantare, meaning “to sing”) is the practice of chanting from the biblical books in the Jewish canon. It is often referred to by the Yiddish word . The practice goes back to the time of Ezra, when the Jewish people returned from their Babylonian exile following the destruction of the first Temple (about 510 B.C.E.).

Realizing that the people had stopped observing the laws of the , Ezra took it upon himself to read portions of the Law every time he could assemble an audience. Sabbaths and festivals provided obvious opportunities; so, too, did market days, when large groups would gather to buy, sell, and catch up on local news. Market days were Mondays and Thursdays, and so, to this day, the Torah is read publicly at least three times each week.

Learn to decipher trope, the notations used in chanting Torah and Haftarah, here or here.

Of course, Ezra did not have the benefit of modern acoustics, microphones, or even the undivided attention of his congregation. Ezra stood in the marketplace surrounded by squawking chickens, braying animals, and unruly children, and competed with the sounds of life. Exaggerating the highs, lows, and cadences of normal speech, Ezra projected the holy texts in a style caught somewhere between speaking and full-blown singing.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Formalizing the Practice

Ezra did not read the Torah in the manner common today. In fact, it is assumed that he differentiated only the beginnings, middles, and ends of verses. The notion of chanting the Bible was an evolving one that gradually became accepted and musically more elaborate. By the second century, Rabbi Akiva (ca. 50-135 C.E.) demanded that the Torah be studied–by means of chant–on a daily basis (B. Sanhedrin 99a).

Rav (third century) is quoted in several Talmudic discussions as understanding Nehemiah 8:8 (in which Ezra’s public reading is described) as referring to punctuation by means of melodic cadences. Johanan (d. 279 C.E.) of the Tiberias Academy is credited with fixing the notion that it is not only customary, but required, that the reader use the proper musical chant. He states categorically, “Whosoever reads [the Torah] without melody and studies [Mishnah] without song, to him may be applied the verse (Ezekiel 20:25): ‘Moreover I gave them laws that were not good, and rules by which they could not live”‘ (B. Megillah 32a).

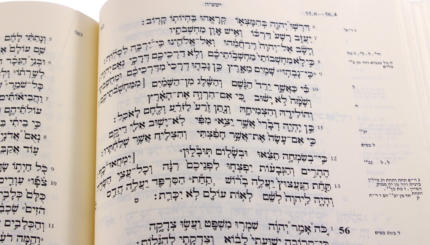

We must note that the biblical texts available to Ezra, to the Rabbis of the Talmud, and even through the sixth century, were like the Torah scrolls in use today: devoid of any vowels, punctuation, and grammatical indicators. Ezra and those who followed him depended upon an oral tradition for their understanding of the proper pronunciation and accentuation of the sacred texts. As chanting became more widely practiced, a system of hand signals common in the ancient Near East began to be employed. This system, called “chironomy,” required an assistant to the reader to use gestures of the hand and fingers to visually illustrate the proper musical rendition of the text.

The Masoretes

Much later, in the second half of the first millennium, a group of largely anonymous Masoretes (“conservators of the tradition”) redacted the oral tradition inherited from Moses. These scholars notated the missing vowels, punctuation, and grammatical organization into the text using a set of 28 symbols called “neumes” (te’amim). Later the neumes were also used to provide musical direction to the reader. Simple (and sometimes more complex) melodic patterns were attached to each symbol to provide for a fully detailed rendition of the biblical text.

As the system became more elaborate, chironomy became of increasing importance, since readers were now compelled to provide more sophisticated musical renditions based upon varying combinations of these neumes. Moreover, while the neumes appeared in various versions of the Bible acceptable for study purposes, it remained customary to chantpublicly from a non-punctuated scroll. Chironomy remained commonplace in the time of the Masoretes and through the 11th century and has enjoyed some renewed interest in our time.

Excerpted with permission from Discovering Jewish Music (Jewish Publication Society).