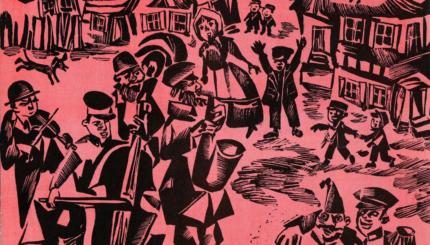

Perhaps Jewish “humor” began when somebody wondered if maybe, just for once, God could choose someone else! Or, perhaps, Jewish humor was never really humor in the ordinary sense of the word; rather, it was a weapon in the uphill battle for survival. With no land or army of its own–with none of the rights normally given to citizens–staying alive as a people was a decidedly open question.

Nathan Ausebel claims that “as identifiable types, schlemihls and schlimazls must have sprung into being with the first drastic economic discrimination against Jews by the Byzantine emperors, beginning with Justinian (530-56).”

Powerless by any conventional standards, Jews became masters in the arts of self-mockery. However, rather than merely turning the sharp edges of their humor against the oppressor, they tended to turn it inward, to establish their own humanity by comic extensions of universal follies. In Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious, Freud makes the following observation:

The occurrence of self-criticism as a determinant may explain how it is that a number of the most apt jokes… have grown up on the soil of the Jewish popular life. They are stories created by Jews and directed against Jewish characteristics…. I do not know whether there are many other instances of a people making fun to such a degree of its own character.

Stories of Chelm

It is from these roots that the schlemiel gradually became a stock figure of Jewish anecdote. In some stories, he seems to be a citizen of Chelm [a mythical village populated, according to Jewish folklore, by fools] and, like each of its citizens, a misrepresenter of reality. For example, the medieval story of Shemuliel is often retold as if it happened in Chelm — with the schlemiel getting the sort of “explanation” he deserves:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

A young scholar of Chelm, innocent in the ways of earthly matters, was stunned one morning when his wife gave birth. Pell mell he ran to the rabbi.

“Rabbi,” he blurted out, “an extraordinary thing has happened! Please explain it to me. My wife has just given birth although we have been married only three months! How can this be? Everyone knows it takes nine months for a baby to be born!”

The rabbi, a world-renowned sage, put on his silver-rimmed spectacles and furrowed his brow reflectively.

“My son,” he said, “I can see you haven’t the slightest idea about such matters, nor can make the simplest calculation. Let me ask you: Have you lived with your wife three months?”

“Yes.”

“She has lived with you three months?”

“Yes.”

“Together–have you lived three months?”

“Yes.”

“What’s the total then–three months plus three plus three?”

“Nine months, Rabbi!”

“So… what is the problem?”

Usually, though, the “Wise Men of Chelm” stories focus on the collective foolishness of the townspeople. They are forever meeting to solve the great issues of the time–as the following story suggests.

The people of Chelm were worriers. So they called a meeting to do something about the problem of worry. A motion was duly made and seconded to the effect that Yossel, the cobbler, be retained by the community as a whole to do its worrying, and that his fee be one ruble per week.

The motion was about to carry, all speeches having been for the affirmative, when one sage propounded the fatal question: “If Yossel earned a ruble a week, what would he have to worry about?”

Motke Habad

However, if the “Wise Men of Chelm” stories portray an ironic sort of wisdom, the Motke Habad stories [a figure from Jewish folklore] shrink the faults of the many into the characteristics of a single figure. Like the superhuman exploits of a Paul Bunyan in an American frontier context, the machinations of Motke Habad became a barometer for the shtetl‘s [village’s] sensibility. As one collector of Jewish folklore puts it:

He [Motke Habad] is the Jew who is forever trying to make ends meet, but always in vain. Good-natured, well-intentioned, and desperately eager to get ahead in the world, fate seems to be constantly against him, and he fails no matter to what he turns. He is the archetypal schlemiel and the mock-pathetic hero of countless anecdotes.

Sometimes he has an unconscious hand in the making of his various “failures” as the following story makes clear:

Motke became a teamster, but he found the horse consumed all the profits. He determined to wean the beast from the habit of eating, and began by depriving it of oats one day a week, then two days, then three. After a month the horse seemed well on its way to learning how to get along with almost no oats at all, when it suddenly collapsed and died. Motke was beside himself with grief. Standing over the beast, he groaned, “Woe is me! Just when my troubles were almost over, you have to give up and die!”

At other times, however, he simply overextends himself, getting so engrossed in the “forests” of life that he keeps bumping into the “trees.”

Motke Habad was once summoned by the local Polish landowner and told to go to the fair in a neighboring town to purchase a French poodle for the baroness.

“Certainly!” cried Motke, all eagerness. “And how much is your Excellency willing to spend for a first-class French poodle?”

“Up to 20 rubles.”

“Out of the question!” Motke snapped. “For a really first-class French poodle one must pay at least–at least–at least 50 rubles!”

The nobleman tried to dispute this, but Motke was so positive that the other finally yielded. Handing over the 50 rubles, he told Motke to hurry off, whereupon the schlemiel became covered with confusion and stammered: “Yes, Your Excellency, I go, I go. B-But please, Your Excellency, what exactly is a French poodle?”

But for all his misdirected ambition, Motke is not the sort of overreacher one finds in the tragic stories of, say, a Faust or Macbeth. The Motke Habads of Yiddish anecdote always have decidedly smaller goals and their “failures” allow for good cheer on the part of protagonist and reader alike.

Failures of All Sorts

As I have suggested earlier, the schlemiel’s failures come in a variety of sizes and shapes. At times he is the cuckolded one (Shemuleil) or the amateur entrepreneur (Motke). On other occasions, he is the henpecked husband — a fate as much to be feared as cuckoldry and deeply entrenched in a sensibility that had strong leanings toward misogynism. In these stories, the shrewish wife becomes a grotesque symbol of all that the shtetl’s male population unconsciously feared. As always, the laughter that generated from such humor was likely to be terribly uncomfortable, particularly when the fate of the schlemiel looked to be only an exaggeration or two away from their own.

A man was married to a shrew who ordered him around the livelong day. Once, when she had several women friends calling on her, she wanted to show off before them what absolute control she had over her husband.

“Schlemiel,” she ordered, “get under that table!”

Without a word the man crawled under the table.

“Now, schlemiel, come out!” she commanded again.

“I won’t, I won’t” he defied her angrily. “I’ll show you I’m still master in this house!”

The official religion may have talked about the nobility of their suffering, the God-given character of their mission, etc., but as Mr. Clement Greenberg has suggested: “When religion began to lose its capacity, even among the devout, to impose dignity and trust on daily life, the Jew was driven back on his sense of humor.”

Humor as Weapon

It was Yiddish — rather than Hebrew -0 which emerged in the lands of the Diaspora as the language of daily living…. It was primarily a folk tongue, a perfect vehicle for the cultural values known as Yiddishkeit and the continued survival of the species. If the “goyim” could boast of armies and power, the shtetl Jewry could offer up sharp retorts by way of putting things into perspective. Jewish humor, then, was a way of building in a certain amount of victory.

In the face of world’s injustice — and, at times, even God’s — the shtetl Jew solidly maintained his innocence. As a people, they often characterized themselves as luckless schlimmazzels.

At the same time, however, they also saw the schlemiel’s ineptitude in socioeconomic matters as an extended metaphor of their own. Far from being a symbolic shorthand for the masochistic preoccupations of the Jewish psyche (as Freud and Reik tended to see it), the schlemiel was a point of reference for the community which surrounded him. As the acknowledged “fool,” he was free to criticize in a way that those with more vested interest in the “realities” could not. Because he was a character of ineptitude, a humbling misrepresenter of reality, his comic victimhood helped to sustain those who were only partially schlemiels. Jewish humor is often described as a “laughter through tears,” and in both the recognition and definable distance between the schlemiel and the average shtetl dweller there was plenty of room for both possibilities.

In some sense, every shtetl Jew was a schlemiel–at least to the extent that he could identify with those who had a hand in their own undoing. Max Nordau’s term luftmentsh (literally “air-man”) suggests that such shtetl residents lived on “air,” continually hatching up schemes that had no substance.

On the other hand, the schlemiel is often portrayed as a character who is totally unaware of his folly and, in this sense, he allows for a sort of one-upsmanship on the part of his audience. After all, it is nobody’s fault if a man is a schlimmazzel. He is genuinely deserving of pity. But a schlemiel–well, him you could laugh at!

Reprinted with permission from The Schlemiel as Metaphor: Studies in Yiddish and American Jewish Fiction (Southern Illinois University Press).

shtetl

Pronounced: shTETTull, Origin: Yiddish, a small town or village with a large Jewish population existing in Eastern or Central Europe in the 19th and early-to-mid 20th century.