The term “canon” refers to the closed corpus of biblical literature regarded as divinely inspired. The Hebrew biblical canon represents a long process of selection, as testified to by the Bible itself, which lists some 22 books that have been lost to us, no doubt, among other reasons, because they were not included in the canon. Books were only included if they were regarded as holy, that is, divinely inspired.

The Hebrew Bible is divided into three parts, (Pentateuch), Prophets and Writings. This division is not strictly one of content; it derives from the canonization process in that the three parts were closed at separate times.

Torah

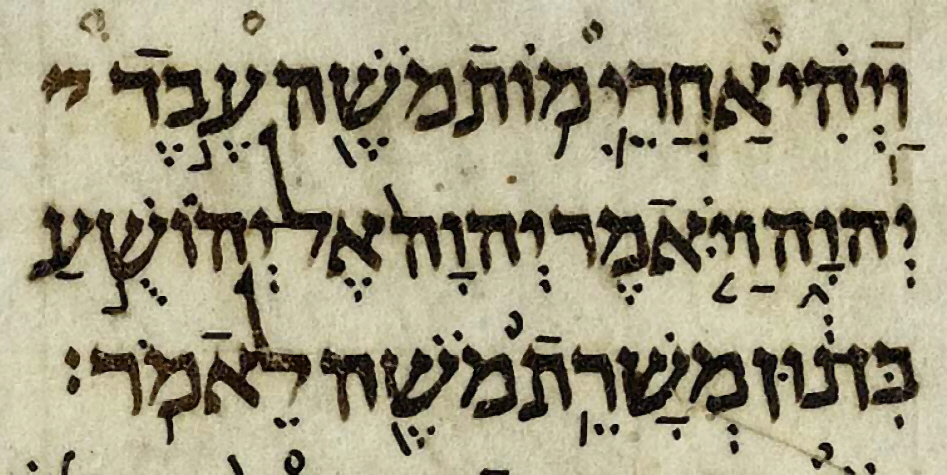

“The Torah of Moses” was already the name for the first part in the various post-exilic books. We will not attempt here to deal with the complex questions regarding the history and authorship of the Torah. Suffice it to say that a unified, canonized Torah was available to Ezra for the public reading which took place in approximately 444 B.C.E. Further, the various legal interpretations (midrashim) found in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are themselves a result of the issues raised by a Torah in which there are apparent contradictions and repetitions. It can therefore be stated unquestionably that the canonization of the Torah was completed by the time of Ezra and Nehemiah.

The Prophets

Later rabbinic tradition asserts that prophecy ceased with the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. E. In effect, this meant that books composed thereafter were not to be included in the prophetic canon, the second of the Hebrew Bible’s three parts. This view can be substantiated by the absence of later debate about the canonicity of the prophets, the lack of Greek words in the prophetic books, and the inclusion of Daniel and Chronicles in the Writings rather than in the Prophets. It must be the case, therefore, that the Prophets were canonized late in the Persian period, probably by the start of the fourth century

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The Writings

The Writings are a diverse collection. Some of the books included in this corpus are earlier than the canonization of the Prophets and were placed in the Writings because of their literary form or because they were regarded as having a lesser degree of divine inspiration. Other books appear in this collection because they were authored after the canon of the Prophets was closed. As already mentioned, this was the case with Daniel and Chronicles. Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes are regarded by some scholars as of Hellenistic origin, but rabbinic tradition attributes them to King Solomon. Daniel is widely regarded by modern scholars as having been written in the Hellenistic period. There is no evidence at all for the oft‑repeated view that the Scriptures were formally canonized at Yavneh (in the first centuries of the Common Era, following the destruction of the Temple.)

While virtually all the Writings were regarded as canonical by the time of the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., arguments continued regarding the status of Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Esther, and these disputes are attested in rabbinic literature. Second Temple literature indicates that a collection of Writings existed as early as the second century B.C.E. but was not regarded as formally closed.

Canonization and Intergroup Relations

The unfolding of the history of Judaism, and indeed of Christianity and Islam as well, takes place against the background of the interpretation of a revealed, authoritative body of literature. For Judaism this corpus is the text of the Hebrew Bible. The notion of a canon provides a fixed consensus on the contents of this body of sacred literature and, therefore, helps to give unity to the diverse interpretations proposed by the varieties of Judaism encountered throughout history.

It was the decision of the Christians to reopen the canon for a moment, and to place the New Testament within it, that created one of the basic disagreements separating Judaism from Christianity. The Hebrew biblical canon drew the lines within which Judaism was to develop and provided grist for the mill of a long and varied history of exegesis. The concept of a canon, with the attendant notions of authority and sanctity, endowed the Hebrew Scriptures with their enduring place in the history of Judaism.

Reprinted with permission from From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism (Ktav).

Tanach

Pronounced: tah-NAKH, Origin: Hebrew, Hebrew Bible (an acronym for Torah, Nevi'im and Ketuvim, or the Torah, Prophets and Writings).