What is the soul? Look for it, and it can’t be seen; define it, and it eludes description. And yet, for the ancients, the idea that life could exist without a soul was unimaginable. However, the ic and kabbalistic rabbis did not make a strict distinction between body and soul, either. Unlike, for example, Plato, most Jewish thinkers had a notion of life-energy that was quasi-materialistic. The spiritual world and the material world were interwoven, and actions in one could directly affect the other–for better or for worse.

The Power of Creation

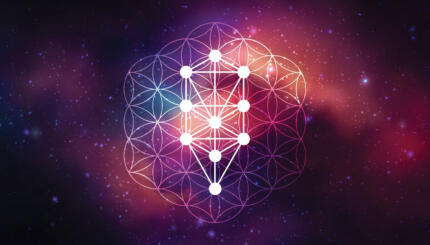

The most important process in the material world, for most of the Kabbalah, is that of creation itself. This, after all, is what God does: creates the world and brings it into being. And it is what humans, in their deepest imitation of God, do as well. Sexuality, reproduction, differentiation, and the bringing forth of life were considered great cosmic mysteries and awesome powers bestowed upon human beings. Spiritual production, too, was important to the kabbalists: A person’s deeds create worlds, order the cosmic array, and participate in the divine process of destruction and repair.

That’s when all goes right, of course. But what about when the life-energies are misappropriated? What happens when something goes wrong?

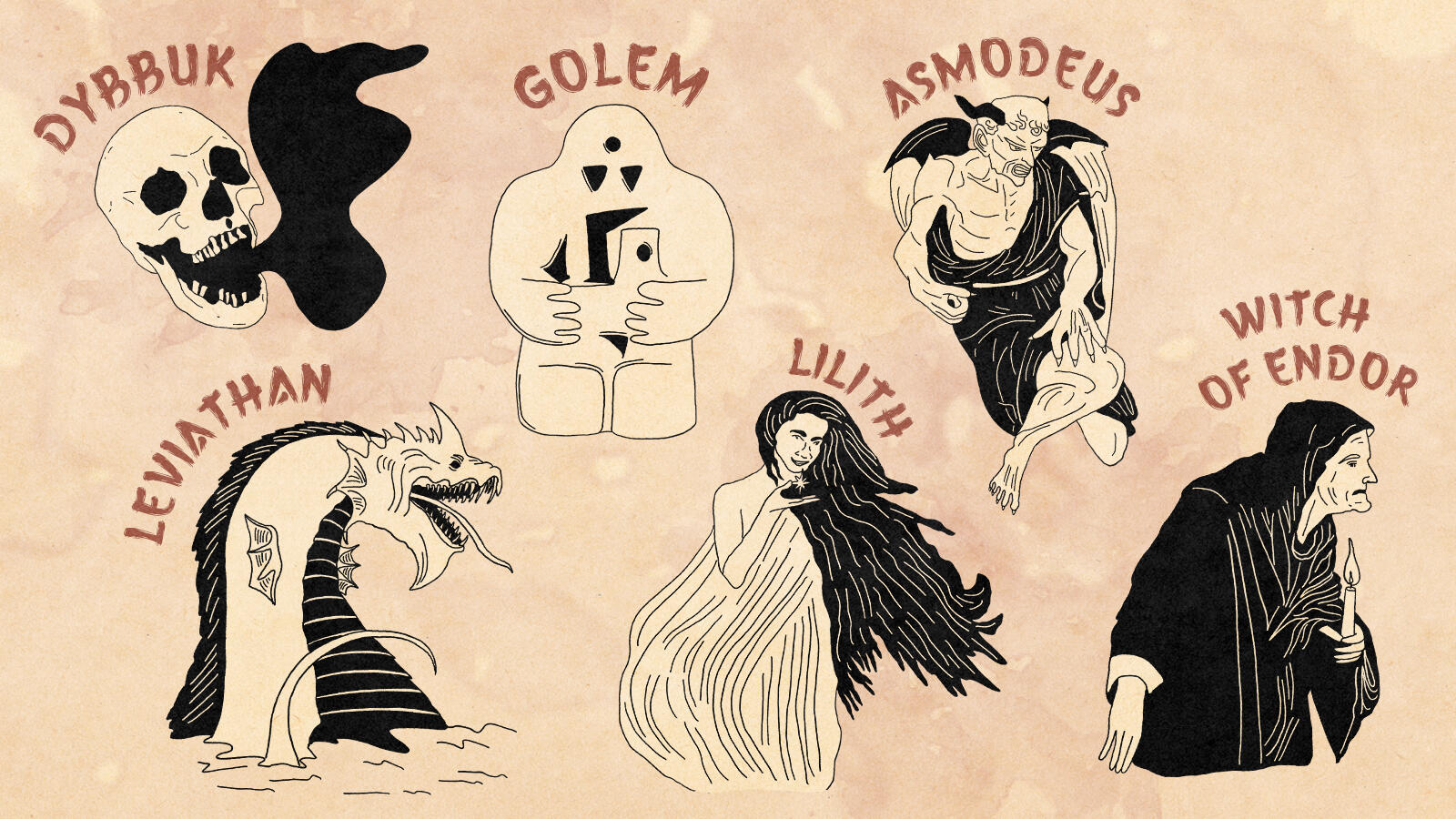

The mythic structure of the provided many colorful answers to that question: demons and dybbuks, golems, and ghosts are all the results of misspent life energy. But the Kabbalah does not develop its ideas out of nowhere; they are part of a long history of Jewish speculation about shedim (demons, also a word used to refer to foreign gods) and demonic personalities such as Lilith.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

As compared with other ancient Near Eastern texts, in which demons play a central role, the Bible is nearly silent about the existence of supernatural beings. But not the Talmud. The Talmud has a rich, though vague, demonology. Houses of study are described as being filled with demons when sexual energy is not properly channeled. Great rabbis are able to perceive demons sitting on the right and left hands of every person. They are able to harness the divine creative energies to create animals which can then be consumed for food. And, in the talmudic world, spirits are everywhere: They haunt dark places, homes, even the crumbs left on the dinner table. For example, consider the omnipresence and omnimalevolence of demons described in theTalmud in Berakhot 6a:

“It has been taught: Abba Benjamin says, If the eye had the power to see them, no creature could endure the demons. Abaye says: They are more numerous than we are and they surround us like the ridge around a field. R. Huna says: Every one among us has a thousand on his left hand and ten thousand on his right hand. Raba says: The crushing of the crowd in the Kallah [yearly public] lectures comes from them. Fatigue in the knees comes from them. The wearing out of the clothes of the scholars is due to their rubbing against them. The bruising of the feet comes from them.”

Rarely does the talmudic literature go into detail about exactly how demons and magical creatures come into being, or whether they are really independent beings “out there,” or merely psychological realities. If the latter, of course, then we today can perhaps understand this foreign-sounding discourse–after all, who among us has not been plagued by “demons” in their work or sexual life? As in the source above,”demons” (mazikim, a word which might be better translated “harmful beings”) could be seen as anything that causes decay, pain, and the depletion of life-energy.

But there’s reason to think that the text in Berakhot is not referring to metaphorical demons, as it goes on to say, “If one wants to discover them, let him take sifted ashes and sprinkle around his bed, and in the morning he will see something like the footprints of a cock.”

Unlike the Talmud, kabbalistic demonology is more detailed. Some demons are formed whenever a man improperly spills his seed–a sin considered so heinous by the Kabbalah because it subverts the creative process. Other demons are, as in the Christian myth, rebellious angels, or in the case of Lilith, primordial humans who disobeyed the divine plan. In all cases, they are instances of life-energy gone awry. In the proper functioning of the cosmos, energy flows like a cycle: down from heaven, then back up in the form of proper ritual action. But when the energy is misappropriated, as in masturbation or rebellion, its intense power falls into the realm of shadow.

The mythic narratives of the Kabbalah may be difficult for us to understand today, but not if we situate them within the deep concerns–particularly those related to conception and childbirth–of the kabbalists and ordinary Jews who lived in a time of great uncertainty. Just as bearing children was central to one’s identity, it was also rife with peril. Miscarriage, infant mortality, illness, and birth defects were all far more common in the medieval world than they are today. Bearing children was awesome and terrifying.

As, of course, was death. If we are all possessed of life-energy, then what happens to that energy when we die?

The Dybbuk

Ideally it returns to its source, but sometimes the process goes wrong. In such cases, a variety of ills may befall the soul. The most well-known of these is the phenomenon of the dybbuk, or possession, when one soul “sticks” onto another. Possession by a dybbuk can happen for a number of reasons. Perhaps the departed soul is sinister and the living person innocent. Or, conversely, the departed soul may have been saintly, but wronged by the living; in this case, possession by a dybbuk is essentially punishment (or revenge) for an improper act. Or,apparently, possession may happen almost at random.

The most popular dybbuk in Jewish cultural history is that of S. Ansky’s well-known play, The Dybbuk (1920), which describes how the soul of a betrayed man comes back to haunt the body of his betrothed.

The Ibbur

There are other “possession” possibilities as well. A soul may visit a person during sleep, bringing messages from the beyond or prophecies about the future, or it may haunt a place, as in popular ghost stories. Sometimes the soul of a departed righteous person may “impregnate” the soul of a living person, the process described by Lurianic Kabbalah as ibbur–though unlike the dybbuk, ibbur is usually positive, not negative. Sometimes a righteous soul undergoes ibbur so it can complete a task or perform a mitzvah. Sometimes it does so for the benefit of the “host” soul. Really, ibbur is no different from possession by a dybbuk—but practically speaking, they are polar opposites, as the former is benign and the other sinister.

In all of these cases, the ordinary processes of life-energy are being diverted, for either positive or negative reasons. And life energy, above all, is powerful. When put to proper ends, the transmission of life energy, by means of sex or supernatural activity, is the godly act of maintaining the cosmic flow. But anything that powerful can also create great evil.

The Golem

Perhaps the most well-known example of this phenomenon, as transmuted by a variety of European sources, is that of the golem, the artificial anthropoid animated by magic. The Talmud relates a tale of rabbis who grew hungry while on a journey–so they created a calf out of earth and ate it for dinner. The kabbalists determined that the rabbis did this magical act by means of permuting language, primarily utilizing the formulas set forth in the Sefer Yetzirah, or Book of Creation. Just as God speaks and creates, in the Genesis story, so too can the mystic. (The word Abracadabra, incidentally, derives from avra k’davra, Aramaic for “I create as I speak.”) Thus, under the rarest of circumstances, a human being may imbue lifeless matter with that intangible, but essential spark of life: the soul.

The kabbalists saw the creation of a golem as a kind of alchemical task, the accomplishment of which proved the adept’s skill and knowledge of Kabbalah. In popular legend, however, the golem became a kind of folk hero. Tales of mystical rabbis creating life from dust abounded, particularly in the Early Modern period, and inspired such tales as Frankenstein and “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” Sometimes the golem saves the Jewish community from persecution or death, enacting the kind of heroism or revenge unavailable to powerless Jews. Often, however, Jewish folktales about the golem tell what happens when things go awry–when the power of life-force goes astray, often with tragic results.

The classic narrative of the golem tells of how Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague (known as the Maharal; 1525-1609) creates a golem to defend the Jewish community from anti-Semitic attacks. But eventually, the golem grows fearsome and violent, and Rabbi Loew is forced to destroy it. (Legend tells that the golem remains in the attic of the Altneushul in Prague, ready to be reactivated if needed; this legend reappeared recently in Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay). Likewise in Paul Wegener’s expressionist film The Golem (1920), the golem is a brutish creature whose powers are all-too-easily turned to destructive ends.

This is, of course, a perfect encapsulation of the same anxiety that underlies so much of the mystical speculation about demons, dybbuks, ghosts, and golems: the power of life is so strong, that it brings both promise and terror.