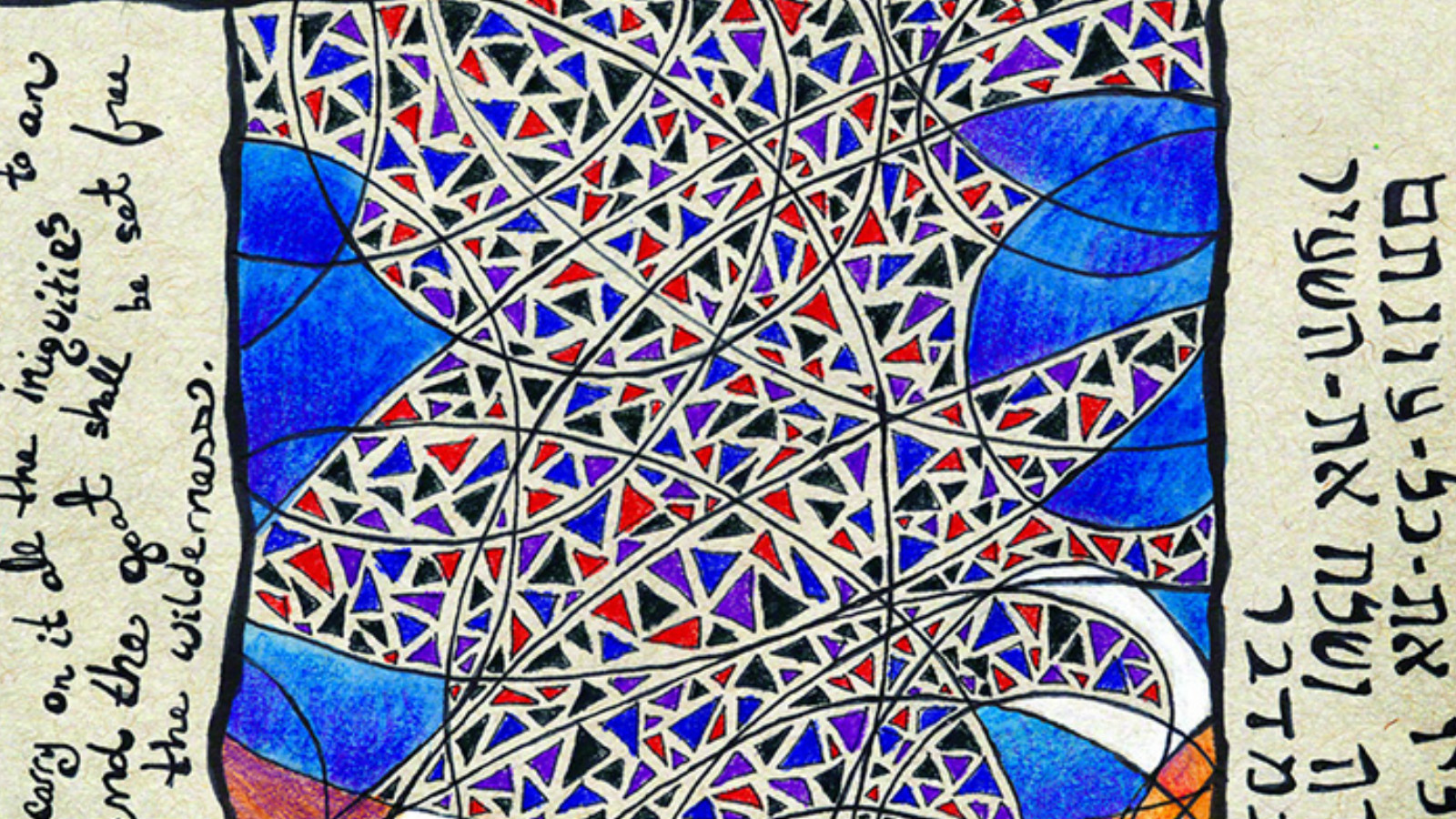

Commentary on Parashat Achrei Mot, Leviticus 16:1-18:30

In the foothills of the Pocono Mountains, a 10-minute drive from a popular Jewish summer camp, there is a hidden treasure: Platz’s, a delicious family restaurant for those with minimal adherence to kashrut and maximal yearning for the palatal bliss of buffalo wings. When sitting down at Platz’s, one first sees a folded napkin, with writing along a side that reads, in capital letters: “DO NOT OPEN THIS NAPKIN.” Perhaps hoping that the recipe for the restaurant’s top secret spicy sauce is inside, all patrons open the napkin.

The owners of Platz’s intuited an unmistakable truth about human beings: We are drawn to secrets. We yearn to see what is hidden and to know what is unknown. In religious terms, revelation means just that. Moses and the Prophets reveal God’s message, and when we read Scripture as a part of our worship, we revere these holy disclosures.

Holiness and secrecy are intricately enmeshed in the Torah, particularly in the business of sacrifices which we read about in the Book of Leviticus. The heart and soul of Leviticus is the Holiness Code (Chapters 17-26), given its name for the repetition of the word for holy, kodesh. But kodesh does not merely mean “holy,” it really means, “separate” or “set apart” in the way we set apart things that we love. The Torah portion that kicks off the Holiness Code, Achrei Mot, is often coupled with Kedoshim. Achrei Mot-Kedoshim could not begin with greater emphasis on the tension between the realms of the hidden and the revealed:

The Eternal One spoke to Moses after the death of the two sons of Aaron who died when they drew too close to the presence of the Eternal. The Eternal One said to Moses: “tell your brother Aaron that he is not to come at will into the Shrine behind the curtain, in front of the cover that is upon the , lest he die; for I appear in the cloud over the cover.” (Leviticus 16:1-2)

The text here reveals a reason for Aaron’s sons’ death that was hitherto hidden — that they died because they came too close to God. That explanation is less popular than the traditional explanation found six chapters prior: that they died because they played with “strange fire,” thus polluting a sacred space and perverting their duty. To the contrary, one might provocatively argue, Aaron’s sons were executed not only because they violated God’s instructions but also God’s privacy!

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Ironically, throughout the subsequent Holiness Code the Israelites are presented with a litany of commandments elucidating how they can, in so many ways, act like God, despite being unable to see the mysterious Eternal One. This is the essential function of the commandments, or mitzvot, here — to give the Israelites their best shot at acting God-like, embodying their essential characteristic of being created b’tselem Elohim, in God’s image.

The commandment to the Israelites in the Holiness Code to “be holy for I, the Eternal your God am Holy,” is not self-evidently reasonable. If the Israelites had limitation in beholding God within the narrative of the Torah itself, how much more so is God’s presence elusive for the Jewish people in society today. The Rabbis insisted in the Talmud, “the age of miracles is over.” Standing at Sinai, as tradition says all Jews have done, requires immense imagination; similarly, “coming out of Egypt,” demands an annual Passover seder (with four glasses of wine, mind you). In other words, God’s insistence in Leviticus on remaining unseen has become rather convenient for the modern Jew. As the says, the Holy One “dwells in the covert.” (Numbers Rabbah 12:3)

Yet, so too does corruption. So it is that both holiness and profanity somehow, dwell in secrecy. Secrecy is not just a religious concept — it plays a role in our everyday lives. From our youngest years, secrets can be as playful as peek-a-boo. Secrets can also be necessary: Picture a world without any confidentiality, a world with no privacy. And, of course, we know that secrecy can also be hurtful; ask any kid on the playground who doesn’t know the secret handshake.

To witness the perniciousness of secrets today we need look no further than the front page of any major newspaper on any given day of the week. Headlines are riddled with speculation about conspiracies, and terms like, “fake news” and “alternative facts” have now become shorthand. Corruption is always cloaked under the thick veil of secrecy, regardless of political party.

In Sissela Bok’s book Secrets: On the Ethics of Concealment and Revelation, she suggests that we adopt a neutral definition of secrets. The problem is not with the secrets themselves, but with the treatment of the secrets: what and how we conceal and reveal. Bok contends, “Secrecy is as indispensable to human beings as fire, and as greatly feared.” We could say the same about God, in the story of Leviticus: indispensable and feared.

God is the biggest secret of all. What and how God conceals and reveals — and how the human being engages in this duality — is often a matter of life or death. In this portion God says, “I appear in the cloud over the cover.” Over the cover, that is, of holy ark. That distinct space is bookended with two cherubs, one on each side. The text tells us very little about these figurines. They appear only in one other context: the story of Eden. After humankind is kicked out of the garden, those two cherubs stood guard. When sculpted above the ark, they continued to do so. They stand, today, as biblical symbols of secrecy.

We will always want to know every secret. We will always want to know what is inside. Everyone who eats at Platz’s knows this. Inside that napkin, they discover words, “Thank you for dining with us.”