As a general rule, all denominations of Judaism prohibit suicide (including assisted suicide) and euthanasia. However, there is some room for nuance on the matter.

Judaism teaches that we do not own our bodies; our bodies belong to God, and we do not have the right to destroy them. Furthermore, our lives are not simply needed for utilitarian purposes. Each person is sacred, having been created in the image of God, and there is thus a value to life regardless of one’s relative quality or usefulness. Not only is human life itself sacred, but every moment of life is valued, and there is thus an obligation to attempt to save all life, regardless of how much time a person has left to live.

The , in the fouth chapter of Sanhedrin, explains:

It was for this reason that Adam was first created as one person, to teach us that anyone who destroys a life is considered by Scripture to have destroyed an entire world; and anyone who saves a life is as if he saved an entire world.

Because of the belief that God owns us and that we thus have limited autonomy, and the ruling of Maimonides (Hilkhot Rotzeah 2:7) that a murderer is liable for capital punishment “whether they killed a healthy individual or a sick person on the verge of death, or even a dying person,” Jewish law prohibits most forms of bodily damage, suicide and assisted suicide. Jewish law also prohibits euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Indeed, even “passive euthanasia” (in which the the doctors don’t take the patient’s life but simply allow him or her to die) is sometimes prohibited when it involves the omission of certain therapeutic procedures or withholding medication, since physicians are charged with prolonging life.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Not only do all Orthodox rabbis prohibit physician assisted suicide (sometimes referred to as “medical aid in dying”), but the Conservative movement’s committee on Jewish law and standards has validated Rabbi Elliot Dorff’s opposition to euthanasia and physician assisted suicide (in Matters of Life and Death, 185 ). Although Reform Judaism grants its adherents much more personal decision-making autonomy than other denominations do, the Reform Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) has issued a responsum “On the Treatment of the Terminally Ill” in which it prohibits euthanasia, though there are individual Reform rabbis who have defended assisted suicide .

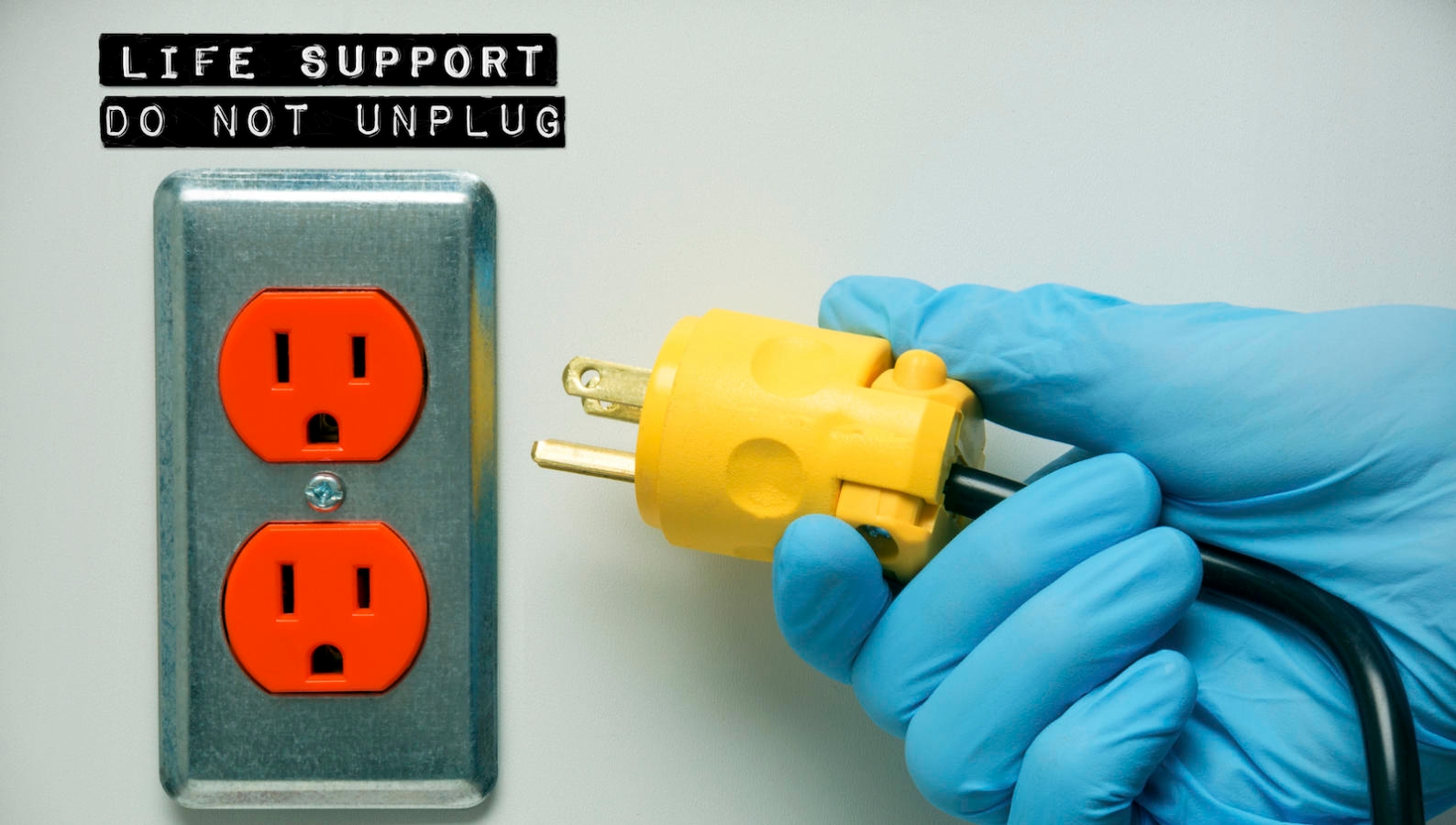

While assisted suicide and euthanasia are taboo, there are certainly situations in which Jewish law permits withholding aggressive life-sustaining treatments, and according to many Conservative and most Reform rabbis, this even includes withdrawing life-sustaining interventions.

Furthermore, although most rabbis prohibit physician-assisted suicide, it is still possible to have compassion for the suffering of terminally ill individuals who are contemplating such a decision without endorsing or condoning it. After all, there are certain cases of suicide, such as that of King Saul recorded in the book of I Samuel, when he falls on his sword in order not to be captured by the Philistines (I Samuel 31:3–4), that Jewish law does not endorse, but for which it offers sympathy and permits traditional burial and mourning practices. Learn more about Judaism and suicide here.

In fact, there are even times when Jewish law may permit praying for a suffering terminal patient to die, while at the same time obligating us to do everything possible, including violate the laws of Shabbat, to prolong his or her life. Thus, even while prohibiting this behavior in practice, there is room for showing some level of understanding and compassion to the patient.

This permission to pray for a terminal patient to die is based on the story of the death of Rabbi Yehudah Hanasi, the author of the Mishnah and one of the greatest ic rabbis. The Talmud (Ketubot 104a) tells us that as he was dying in bed:

The maidservant of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi ascended to the roof and said: The upper realms are requesting the presence of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, and the lower realms are requesting the presence of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. May it be the will of God that the lower worlds should impose their will upon the upper worlds. However, when she saw how many times he would enter the bathroom and remove his phylacteries, and then exit and put them back on, and how he was suffering with his intestinal disease, she said: May it be the will of God that the upper worlds should impose their will upon the lower worlds. And the Sages, meanwhile, would not be silent, i.e., they would not refrain, from begging for mercy so that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi would not die. So she took a jug and threw it from the roof to the ground. Due to the sudden noise, the Sages were momentarily silent and refrained from begging for mercy, and Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi died.

We see from this text that although physician assisted suicide may not be advocated by most rabbinic authorities, we can have compassion for the suffering of a dying patient. We must do everything to prolong life, but do nothing to prolong the dying process. As we can keep a patient alive, we must do so, unless the benefit of such actions is counterbalanced by their causing extreme pain and suffering. At that point, Judaism permits a compassionate response of allowing the death process to occur with appropriate palliative care, if this is what the patient or their surrogate desires and their rabbi has ruled accordingly for that specific case.

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.