Dreams have long played an important role in Jewish tradition. In the Bible, dreams are portrayed as a means of communicating messages from God and as a source of truth about the present and the future. The Talmud imagines that dreaming can tap into the powers of prophecy, while the kabbalists understood dreams as journeys of the soul that may summon messengers or ward off frightening night time visions. Taken together, these various traditions portray not only dreaming, but sleep itself as a sacred activity.

Dreams play a central role in some of the major narratives of the Bible. The patriarch Jacob dreams of a ladder to heaven with angels climbing up and down. Joseph dreams of a sheaf of wheat, with twelve other sheaves of wheat bowing down to it. In the Book of Kings, God comes to King Solomon in a dream to grant the gift of wisdom. Some biblical dreamers, like the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, are warned of disaster, while others, like Pharaoh’s butler, dream of deliverance. All these dreams are seen as containing important messages that can be divined by dream interpreters like Joseph and Daniel, both of whom seem to derive their interpretations from a divine source.

Yet a counter trend in the Bible suggests a certain anxiety around dreams and their interpretation. Deuteronomy 13:2-4 forbids the people from listening to a dream-diviner who contradicts the words of Torah. The prophet Jeremiah expresses disdain for prophets who get their prophecies from dreams. The concern seems to be that a dreaming prophet may offer non-normative wisdom that goes against the sacred text. This worry is reflected in God’s warning to Moses in Numbers 12:6, which states that while future prophets may receive communications by visions or dreams, this is not the case with Moses himself, who communicated directly with God “mouth to mouth.” Another concern might be that dream prophecy empowers those farther from the halls of power and education, such as women and/or non-sanctioned spiritual practitioners.

The Talmud too is concerned with the strangeness of dreams. In Tractate Berakhot, the Talmud regards dreaming as one-sixtieth of prophecy; the remainder it calls devarim b’teilim, nonsense or idle things. How does one sift the prophetic wheat from the chaff of nonsense? The Talmud recommends consulting a dream interpreter, yet dream interpreters, like Torah interpreters, may have different opinions. The Talmud records the story of one sage who went to 24 dream interpreters, each of whom offered a different — and true — interpretation. Like the Torah itself, dreams can have multiple meanings.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The Talmud offers several rituals for “healing” a dream — that is, shifting its meaning in a more positive direction. One ritual is to recite a special prayer asking for a dream to receive healing. Another is the convening of a “dream court” of three people to repair the dream by reciting biblical verses as incantations. The Talmud also notices the use of puns in dreams, saying, for example, that anyone who sees an elephant (pil) in a dream will receive a miracle (pele). The Talmud contains the cryptic statement that “a dream that has not been interpreted is like a letter that has not been read.” One way to understand this is that dreams are communications from the beyond, and if we want to benefit from them we need to pay attention to our nightly mail.

The medieval mystics furthered developed Jewish dream traditions, regarding dreaming as a form of soul journeying. The Zohar, the principal kabbalistic text, states: “When a person lies in bed, the soul goes out and wanders the world above.” In kabbalistic sources, dreamers are said to visit the world of souls, learn truths from angels, or get accosted by demons. The purpose of dreams, according to the Zohar, is not only prophecy, but addressing the worries of the dreamer or inspiring people to transform their lives.

Hayyim Vital, a 16th-century kabbalist who lived in Safed, in northern Israel, recorded dreams and dream interpretations from wise women as well as rabbis. Vital imagined that dreams show dreamers their “soul-root” — the true nature of their identity. Nearly two centuries later, the Baal Shem Tov, the father of the Hasidic movement, taught that when we dream, we encounter the souls of the things we see and experience during the day. Gluckel of Hameln, a German-Jewish diarist, also believed dreams to be a source of otherworldly knowing.

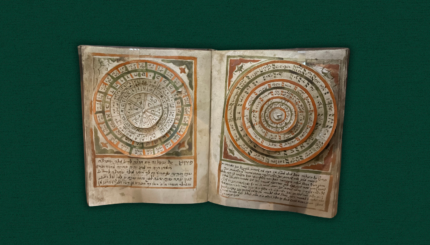

In some Jewish traditions, these messages weren’t merely spontaneous nocturnal occurrences, but could be summoned through magic. Elaborate rituals — including fasting, turning garments inside out, Hebrew prayers and incantations, magical inscriptions, sleeping in a cemetery and more — were used to summon dream messengers. Rituals and amulets were also used as protection against nightmares, which some believed came from demons. These traditions assume that dreams are a site of sacred connection but also of potential danger, since sleep renders the soul vulnerable.

In modern times, most of these traditions are no longer widely practiced. But some Jewish spiritual practitioners are revisiting them and finding profound meaning in their dreams and those of others. Just as various indigenous traditions understand dreaming as a source of crucial spiritual wisdom and guidance, Jewish dreaming traditions from antiquity to the present continue to see dreams as, at the very least, one-sixtieth of prophecy.