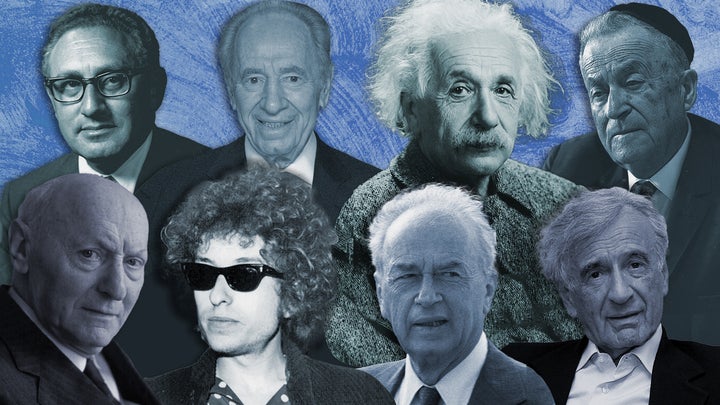

Since the first of the Nobel Prizes was awarded in 1895, about 20 percent of the recipients — over 200 individuals — have been Jewish. The honor is awarded to those who have “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind” in one of six categories: chemistry, medicine, economics, literature, physics and peace. Of the Jewish recipients, some have become household names, even decades or a century after their accomplishments were recognized. Learn more about eight of the more famous Jewish Nobel laureates.

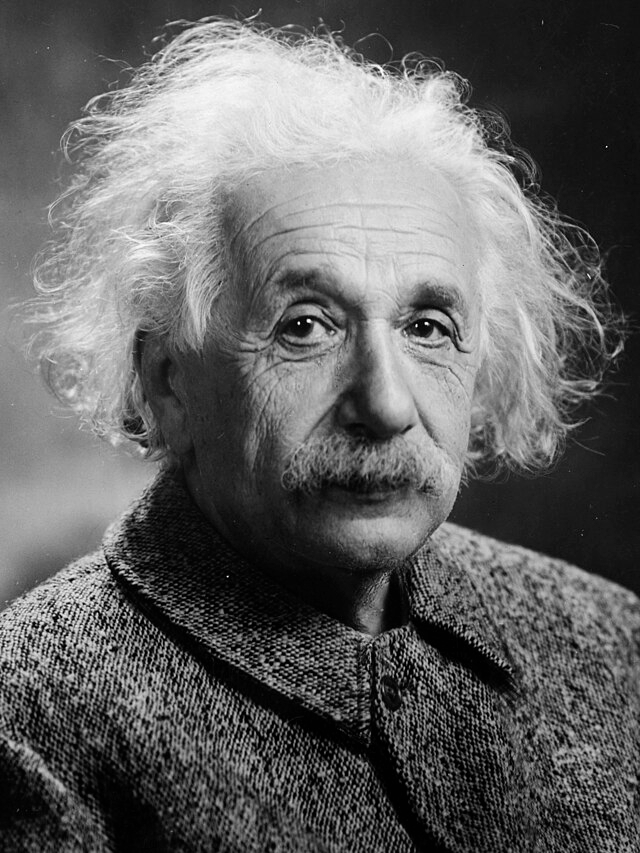

Albert Einstein, Physics, 1921

Albert Einstein is probably best known for his Theory of Relativity, which revised Newtonian mechanics, and his discovery that matter and energy are two sides of the same coin, as represented by the famous equation E=mc2. But he actually won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his discovery of the law of photoelectric effect. Such was his remarkable range as a scientist able to reimagine and more deeply understand the underpinnings of the universe than anyone who came before.

A largely secular Jew, Einstein nonetheless articulated respect for Judaism. He has been quoted as saying that conflicts between science and religion “have all sprung from fatal errors,” and that “science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” Did he believe in the Jewish God? Einstein is on record as describing himself a believer in “Spinoza’s God” — an impersonal, possibly pantheistic view of God who “reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings.”

Einstein supported the creation of the State of Israel, and is considered to have been a cultural Zionist. In the early 1950s, following the death of Israeli president Chaim Weitzman, then Israeli ambassador to the United States, Abba Eban invited Albert Einstein to step into the role, though he declined. Einstein did, however, bequeath his personal library to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem on his death.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

S.Y. Agnon, Literature, 1966

Shmuel Yosef Halevi Czaczkes, pen name S.Y. Agnon (derived from his first published story, Agunot), was born in Galicia in 1888. The son of a rabbi, he was home-schooled and studied the Bible and Talmud until the age of nine. Agnon moved to Germany in the early 1900s, where his novels and short stories were published by Schocken Books and the newspaper Haaretz. A fire in his home led Agnon to settle with his family in Jerusalem in 1924, where he ultimately wrote the majority of work that made him one of the leading figures of modern Hebrew literature. His writing, known for its great depth and humor, captures the cultures and traditions of shtetl Judaism while also wrestling with modern Jewish experience. Similarly, his language mixes ancient and modern Hebrew.

Agnon’s first major publication, Hakhnasat Kalah (The Bridal Canopy), showcases the golden age of Hasidism. Arguably his most celebrated work is Tmol Shilshom (Only Yesterday), which portrays Jewish immigration to Palestine. In 1966, he shared the Nobel Prize with Nelly Sachs, a German Jewish author. Because Agnon was an observant Jew and the award ceremony took place on a Saturday night during Hanukkah, he did not attend until he had made Havdalah and lit Hanukkah candles.

Agnon continues to be a central figure in Hebrew literature and his likeness appears on the 50-shekel bill printed from 1985 to 2014. Additionally, a street in Jerusalem is named after him, and he is memorialized by an exhibit in the Historical Museum in Buchach, where he was born.

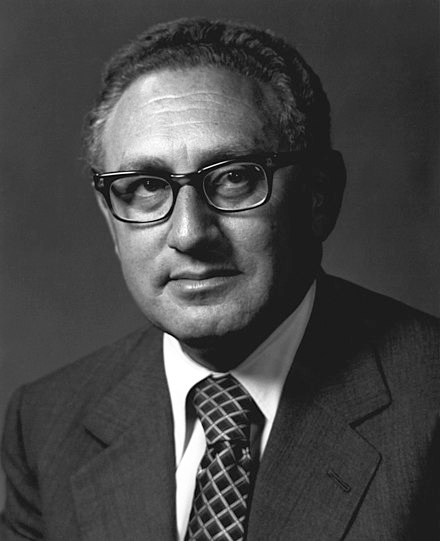

Henry Kissinger, Peace, 1973

Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Secretary of State, was a Jewish refugee who fled Nazi Germany in 1938 and would become one of the most prominent Jews in postwar American politics. He received the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1973 for helping to secure a peace treaty between North and South Vietnam. In addition, Kissinger is known for advising Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and later serving as secretary of state for Presidents Nixon and Ford. He is recognized for building relationships between the great powers during the Cold War. However, he was also widely denounced for his controversial foreign policy decisions, including supporting Pakistan’s military dictatorship and his close association with Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

In the Middle East, Kissinger attempted to lay the groundwork for Arab-Israeli peace. His work resulted in a disengagement of forces during the Yom Kippur War and an interim agreement between Israel and Egypt — despite the fact that President Nixon wanted no Jewish Americans to participate in policy-making regarding Israel. Some of his positions have been controversial within the Jewish community, including reluctance to use his position to pressure the Soviet Union to stop persecuting Jews (which he viewed as not fulfilling American foreign policy objectives) and opposing the creation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (he feared it would create too high a profile for Jews and ignite antisemitism). He has been quoted as saying: “If it were not for the accident of my birth, I would be antisemitic … Any people who has been persecuted for two thousand years must be doing something wrong.”

Isaac Bashevis Singer, Literature, 1978

Isaac Bashevis Singer received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978. His works wrestle with the experience of the Jewish community in a fast-changing world, but also speak to universal human themes.

Born in Poland to a family of rabbis, Singer and his siblings chose to pursue writing over rabbinical school. Singer often wrote about Jewish culture in Poland before the Holocaust, mainly discussing the effects of secularism, modernity and assimilation. He is recognized for his wit, intelligence and descriptions of mysticism and the occult. His debut story, Af Der Elter, (In Old Age), was published in the Warsaw Literarishe Bleter, and his first novel, Der Sotn in Goray (Satan in Goray) was published in Poland. In 1935, Singer moved to the U.S. and worked for the Yiddish newspaper Forverts while also translating books into Yiddush from Polish, Hebrew and German. Among many others, his most significant works include Di Family Mushkat (The Family Moskat) and Der Kuntsnmakher fun Lublin (The Magician of Lublin). He is also acclaimed for his short stories, including the National Book Award-winning A Crown of Feathers. Although Singer exclusively wrote in Yiddish, he is most commended for the English translations.

Elie Wiesel, Peace, 1986

Described as “the most important Jew in America” by the Los Angeles Times, Elie Wiesel received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for “being a messenger to mankind: his message is one of peace, atonement and dignity.” When the Nazis invaded Hungary in 1944, the Wiesel family was deported to Auschwitz. Wiesel’s sister and mother died in the gas chambers, but Wiesel and his father were transported to Buchenwald. There, Wiesel was liberated by American soldiers at the war’s conclusion. He then traveled to a rehabilitation center in France with other child survivors, and in 1948, he moved to Paris where he studied at the Sorbonne and became a journalist for French and Israeli newspapers.

For many years, Wiesel refused to discuss or write about his traumatic experiences, yet Nobel laureate Francois Mauriac encouraged him to help others and himself by opening up that door. Soon enough, his first work Un di Velt hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent), was published, and Wiesel became a leading spokesman on the Holocaust. He committed his life to bringing awareness to the genocide that the Nazis committed during World War II. Wiesel wrote 57 books, of which the most famous is Night, a novel based on his own experiences in the death camps.

When Wiesel won the Nobel Prize, the committee highlighted Wiesel’s commitment to all repressed peoples. Wiesel ran political campaigns for victims of violence, discrimination and oppression in Kosovo, Sudan and Nicaragua. He also was a founding board member of the New York Human Rights Foundation and chairman of The President’s Commission on the Holocaust. When he received the honor, he declared, “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant.”

Read: What Elie Wiesel Taught Me About the Book of Job

Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, Peace, 1994

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 with former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres and chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization Yasser Arafat for their efforts to make peace through the Oslo Accords. Born in Jerusalem, Rabin dedicated his life’s work to the security and welfare of Israel. He joined the Palmach in 1940 as a soldier and commander, and he ultimately rose in the ranks to become the Israel Defense Force’s chief of staff during the Six-Day War. He led his troops to triumph over Egypt, Syria and Jordan, inducing the reunification of Jerusalem. Rabin retired from the army in 1968 and became ambassador to the United States. In 1973, he was elected to the Knesset and eventually became prime minister himself. As prime minister, he signed the Disengagement of Forces Agreements with Syria and Egypt and ultimately became one of the faces of the Oslo peace process.

Shimon Peres immigrated to Palestine in 1934 and joined the Haganah. When Israel achieved independence in 1948, Peres became Israel’s head of navy, where he upgraded the state’s weapons production and established alliances overseas. He later served as Israel’s prime minister (1984-1986 and 1995-1996) and president (2007-2014).

The spirit of the Oslo peace process is perhaps best captured by the famous photo of a handshake between Rabin and Arafat at the White House. A year later, all three were honored with the Nobel Prize. Rabin was assassinated in 1995 by right-wing Jewish extremist Yigal Amir.

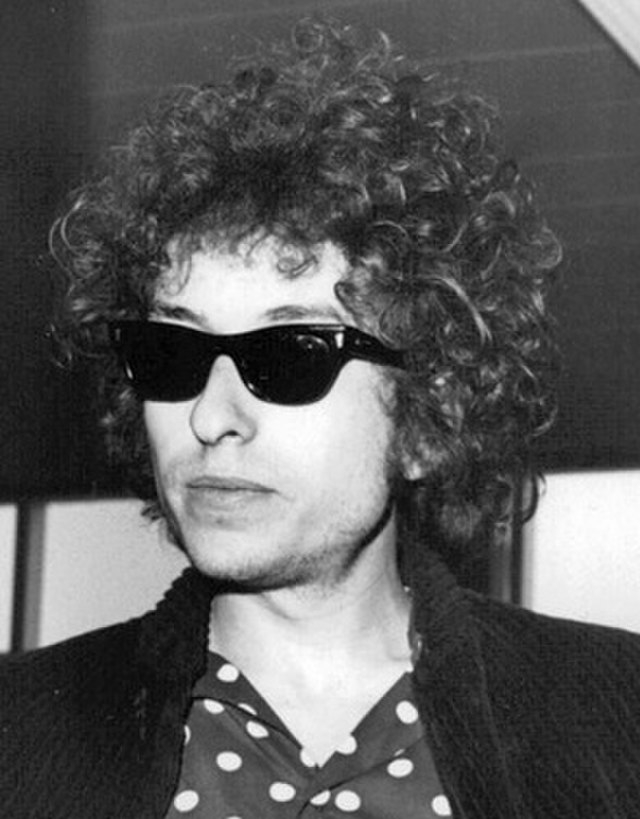

Bob Dylan, Literature, 2016

Singer Bob Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman, is probably best known for hit folk songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” Many of his songs became synonymous with the counterculture of the 1960s. Widely regarded as one of the greatest lyricists of all time, his songs wrestle with the social, philosophical and political struggles of the mid-20th century, while pushing the boundaries of musical convention. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016 for “creating meaningful poetic expressions within the American musical traditions.”

Born Jewish but not particularly vocal about his religion, Dylan’s work nonetheless evinces Jewish influences, especially in the way he plays with the feeling of being an outsider. Though he briefly converted to Christianity in the 1970s and wrote some overtly Christian songs, many of his songs before and after show marked Jewish influence. The opening verse of “Highway 61 Revisited” (1965), for instance, revisits the biblical Binding of Isaac, and his “Neighborhood Bully” (1983) has been described as a “thinly-veiled parable about the Jews.”

Curious about Jews who won the Nobel but aren’t quite as famous? Read all about eight more Jewish Nobel laureates you should know.