Commentary on Parashat Bo, Exodus 10:1-13:16

This week’s Torah portion contains one of my all-time favorite conversations, one of the occasions where two opposing world views are really beautifully, succinctly and clearly articulated.

As the portion begins, the Egyptians have been through seven plagues, but will still not let the Israelites go. Moses now warns them of the next plague, the locust. Pharaoh’s people have had it, they are ready to give in.

And the servants of Pharaoh said to him: ‘Until when will this one be a stumbling block to us? Send out these people that they may worship the Lord their God. Don’t you know yet that Egypt is lost?’

Pharaoh capitulates, sends for Moses and Aaron, and says to them: “Go, and worship the Lord your God.” But Pharaoh also has a question: “Who will be going?”

And now, with his response to Pharaoh, Moses lays the groundwork for universal suffrage and the French and American Revolutions: “With our young people and our old people we will go, with our sons and our daughters…we will go, for it is a holiday to God for us.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Pharaoh’s response is swift: “…Not so, let the male adults go and worship the Lord, for this is what you ask.” Angrily, Pharaoh brings the meeting to an end: “And he drove them out from before him.” The interview is over, the deal is off, and the locusts arrive the next day.

Understanding Judaism

This short exchange between Moses and Pharaoh is crucial to an understanding of Judaism, and monotheism. Pharaoh is a pagan. For him, a religion’s rituals are done by the functionaries or the leaders of the tribe. The rest of the people, the servants and subjects of the king, are dependant on the relationship between the leaders–the priests and the royalty–and the various deities they serve.

Pharaoh can see no reason for everyone to be part of the worship of the Lord. As his ‘secular’ world is arranged–hierarchal, authoritarian, and totalitarian–so is his religious world. It is the religious leadership–in this instance the adult males–who must go and serve the Israelite God. The people should remain behind, enslaved, passive, and hope that the priests get the rituals right, and thereby insure the blessings of their God or Gods.

Pharaoh thinks that only the adult males should go because he does not grasp the notion of freedom for all. He sees Moses and Aaron as the Jewish leadership, to whom, under pressure from their God and his plagues, he is willing to cede some authority. He can not imagine that their God wishes to relate to each and every one of the miserable people he has enslaved. He can not imagine that each of these individuals is a separate entity, standing alone before God.

Moses, on the other hand, explains the core of monotheism to Pharaoh, and to us. All of us, young and old, man and woman, must stand before God. As equals. As individuals. We all must participate in the relationship with the divine. And so, all of Israel must be allowed to go and commune with God in the desert. God, who created every one of us, has a relationship with every one of us.

This is the way Judaism works, and this is why the Jews must leave oppressive, totalitarian, autocratic Egypt, the Egypt that enslaves, the Egypt that rules, for the freedom of the desert. There, and only there, unencumbered by the chains of slavery, oppression, and royalty, each and every individual, on his or her own, stands before the Creator of the Universe. Celebrates before the Creator of the Universe. In fact, we can perhaps say that the specific content of this celebration in the desert is the fact that all of us, young and old, male and female, can stand, and are standing, as independent entities before God. That itself is worthy of celebration.

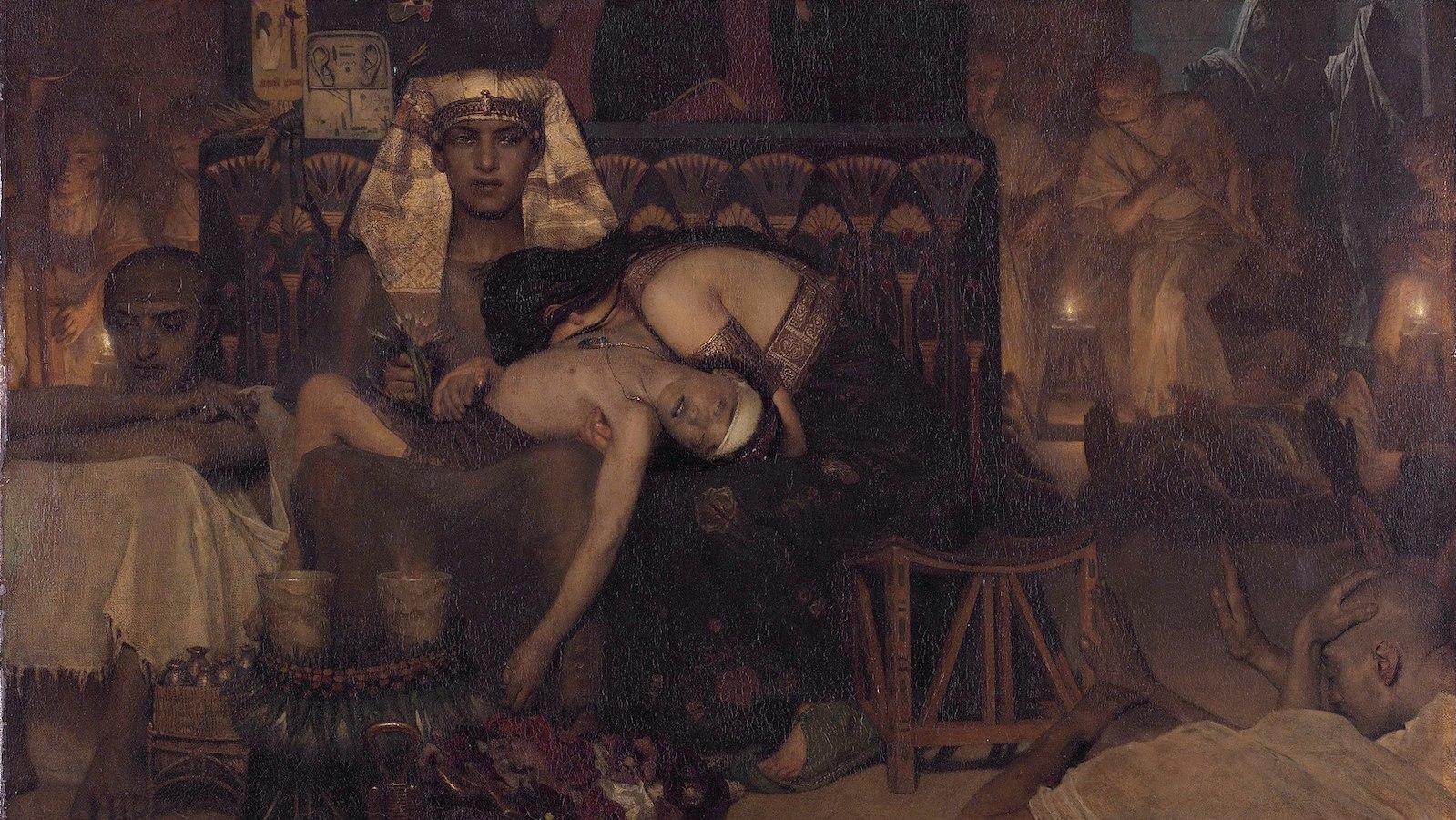

Killing the First Born

As the plagues continue, and reach the awful climax of the killing of the first born, God’s side of this equation is clarified. The reason each and every one of us must stand before God is this: He created us all. He rules us all. In the pagan world, with a plethora, a hierarchy, of Gods, not everyone has the same relationship with one deity or another; not every deity has the same relationship with the world and its creatures. If, on the other hand, there is one, all-powerful Creator, as the plagues prove, we are all equally his creations. We all stand before him equally as his, and only his subjects.

Some of you may be wondering exactly how far I want to really go with this egalitarian thing. In other words, really put my money where my mouth is. Good question.

I do think that what I said above is right, and true. I also think that the Jewish people know that men and women, children and adults, also have to interact, live together, raise families, in community, and that there are ways in which we, as a people, have tried to arrange these interactions, ways worthy of our respect, on the one hand, and our respectful criticism on the other.

Provided by the Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel, a summer seminar in Israel that aims to create a multi-denominational cadre of young Jewish leaders.

parsha

Pronounced: PAR-sha or par-SHAH, Origin: Hebrew, portion, usually referring to the weekly Torah portion.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.