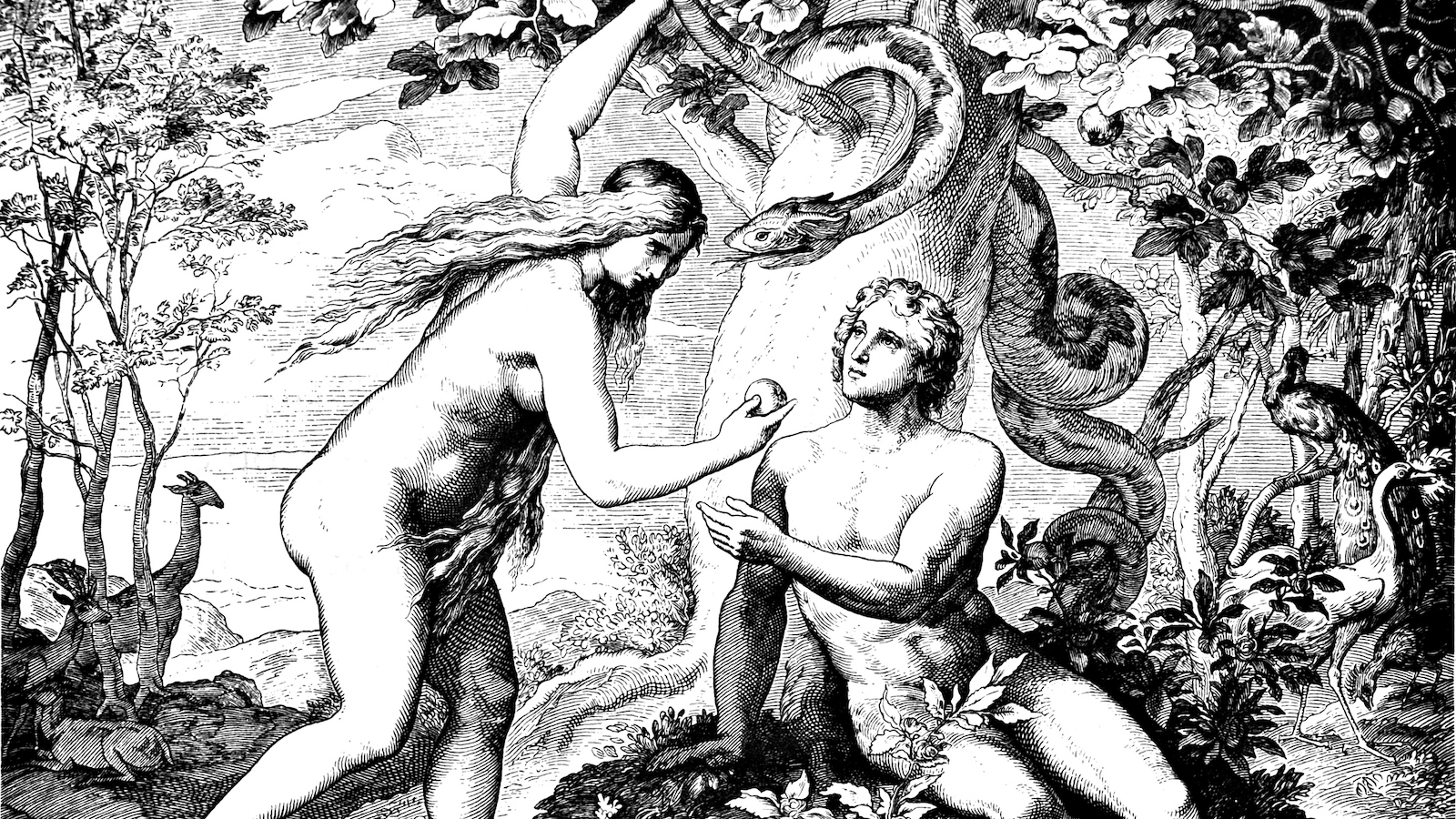

The first woman according to the biblical creation story in Genesis 2–3, Eve is perhaps the best-known female figure in the Hebrew Bible. Her prominence comes not only from her role in the Garden of Eden story itself, but also from her frequent appearance in Western art, theology, and literature. Indeed, the image of Eve, who never appears in the Hebrew Bible after the opening chapters of Genesis, may be more strongly colored by postbiblical culture than by the biblical narrative itself.

For many, Eve represents sin, seduction, and the secondary nature of woman. Because such aspects of her character are not actually part of the Hebrew narrative of Genesis, but have become associated with her in Jewish and Christian interpretive traditions, a discussion of Eve means first pointing out some of those negative views that are not intrinsic to the ancient Hebrew tale.

The Post-Biblical Dilemma

Although Eve is linked with the beginnings of sin in the earliest mentions of her outside the Hebrew Bible—in the Jewish non-canonical Book of Sirach, as well as in the New Testament and in other early Jewish and Christian works—she is not called a sinner in the Genesis 2–3 account. To be sure, she and Adam disobey God; but the word sin does not appear in the Hebrew Bible until the Cain-Abel narrative, where it explicitly refers to the ultimate social crime, fratricide. Another misconception is that Eve tempts or seduces Adam. In reality she merely takes a piece of fruit—not an apple—and hands it to him; they both had been told not to eat of it, yet they both do. Also, the story is often thought to involve God’s cursing of Eve (and Adam), yet the text speaks only of cursing the serpent and the ground. And the Eden tale is frequently referred to as the “Fall” or “Fall of Man,” although there is no fall in the narrative; that designation is a later Christian application of Plato’s idea (in the Phaedrus) of the fall of heavenly beings to earth in order to express the idea of departure from divine favor or grace.

Such views are entrenched in post-biblical notions of Eden, making it difficult to see features of Eve and her role that form part of the Hebrew tale. These features have been largely unnoticed or ignored by the interpretive tradition. This situation, and also the way in which the Genesis 2–3 story appears to sanction notions of male dominance, has made a reconsideration of the Eden tale an important project of feminist biblical study ever since the first wave of feminist interest in biblical exegesis, which was part of the nineteenth-century suffrage movement in the United States. Contemporary feminist biblical study for the most part, but not entirely, has tended to remove negative theological overlay, to recapture positive aspects of Eve’s role, and generally to understand how this famous beginnings account might have functioned in Israelite culture. The literature dealing with Eve and her story is voluminous, and only a sample of the new perspectives can be discussed here.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The First Woman in Genesis 1

The first thing to be noted is the apparent contrast between how the creation of humanity is portrayed in Genesis 1 and its depiction in Genesis 2–3. For literary and theological reasons, the heaven-focused first chapter of the Hebrew Bible (actually, Genesis 1–2:4a) is usually attributed to a Priestly author (or P), whereas the earth-focused Genesis 2:4b-3 creation story is probably an earlier account. The P account has God creating humanity in the divine image (Genesis 1:26). The word for humanity, adam is grammatically masculine and can mean a male and can even be the proper name Adam; but it is often used generically or collectively, as in Genesis 1, to denote a class of living beings, that is, people (rather than animals or God). Traditional translations render it “man” but more recent gender-sensitive translations now render it with inclusive words like “humanity” or “humankind.” A further aspect of creation in Genesis 1 is that adam (humanity) is inclusive; it consists of both “male and female” (zakhar and neqevah); these words generally denote two biological (sexual) categories and are used in the Bible for both people and animals. The simultaneous creation of female and male in the image of God is often interpreted as evidence of female-male equality in the first creation story. However, it is uncertain that these complementary biological categories are also social. In any case, the terms for the two parts of humanity in Genesis 1 are very different in the Garden of Eden story.

The Woman of Eden and Her Partner

The well-known Eden tale begins with the scene of a well-watered garden—so unlike the frequently drought-stricken highlands of the land of Canaan in which the Israelites lived. God has placed there an adam, a person formed from “clods of the earth [adamah]”(Genesis 2:7). This wordplay evokes the notion of human beings as earth creatures: God forms an earthling from the earth, notably reddish-brown arable land (for adam is likely related to adom, the Hebrew word for “red”). Because adam is often a gender-inclusive term, its use here for the first human does not necessarily mean that the first human is a man. Indeed, some feminist readings of biblical inclusive language, and also some rabbinic texts and medieval Jewish commentaries, consider the original human androgynous, as does an ancient Mesopotamian creation tale. Thus God has to divide the first being into female and male in order for procreation and on-going human life to begin. At the very least, because the word adam in Genesis 2–3 is not unambiguously male, it is best rendered “human” until a second person is created.

God tells this first being that anything in the garden may be eaten except for the fruit of a certain tree. God then decides that this person should not be alone and tries animals as companions. Creating animals serves to populate the world with living creatures but doesn’t quite meet God’s intentions. God then performs cosmic surgery on the first person, removing one “side” (NRSV [New Revised Standard Version] “rib”; Genesis 2:21) to form a second person. The essential unity of these first two humans is expressed in the well-known words (Genesis 2:23) “bone of my bones / and flesh of my flesh.” The word ishah is now used for “woman” and ish for “man.” These similar sounding words are probably not from the same Hebrew root, but they do form a striking word play (as do adam and adamah), indicating an essential sameness of the two beings. This unity, a function of the one being split into two, is reenacted in copulation, indicating the strength of the marital bond over the natal one: “Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh” (Genesis 2:24).

The relationship between this first pair of humans is expressed by the term ezer kenegdo (Gen 2:20), translated “helper as his partner” by the NRSV, “fitting helper” in the NJPS (New Jewish Publication Society Version), and “helpmeet” or “help-mate” in older English versions. This unusual phrase probably indicates mutuality. The noun helper can mean either “an assistant” (subordinate) or “an expert” (superior; e.g., god as Helper in Psalms 54:4).); but the modifying prepositional phrase, used only here in the Bible, apparently means “equal to.” The phrase, which might be translated as “an equal helper” or “a suitable counterpart,” indicates that no hierarchical relationship exists between the two members of the primordial pair. They form a marital partnership of the kind necessary for survival in the highland villages of ancient Israel, where the hard work of both women and men was essential. Yet another translation is possible, one that retains the counterpart idea and also take into account that ezer can be derived from a Hebrew root meaning “to be strong, powerful” rather than the one meaning “to help.” The phrase would then be translated “powerful counterpart.” Because women had considerable power in agrarian Israelite households in the Iron Age, this reading is compelling.

This primeval pair have no names. The narrator doesn’t disclose the woman’s name, Eve, until late in the Eden story, right before expulsion from the garden. Although generic adam, often preceded by the definite article (“the human”) appears nineteen times in the Eden story, it is not unambiguously used as the name of the first man until the end of Genesis 4, the Cain and Abel story. Eve is the first human with a specific form of identification.

Disobedience and Its Consequences

The serpent now enters the scene. An intelligent being, it begins a dialogue with the woman, who is thus the first human to engage in conversation (a reflection perhaps of female skill with words?). The woman is the one who appreciates the aesthetic and nutritional qualities of the forbidden tree and its fruit, as well as its potential “to make one wise”. The woman and the man both eat and ultimately are expelled from Eden for their misdeed, lest they eat of the tree of life and gain immortality along with their wisdom. Eating of the forbidden fruit has made them like God, able to know, perceive, and understand “good and bad” — meaning everything. But they must never eat of the life tree and gain immortality too.

This brings us to perhaps the most difficult verse in the Hebrew Bible for people concerned with human equality. Genesis 3:16 seems to give men the right to dominate women. Feminists have grappled with this text in a variety of ways. One possibility is to recognize that the traditional translations have distorted its meaning and that it is best read against its social background of agrarian life. Instead of the familiar “I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing,” the verse should begin “I will greatly increase your work and your pregnancies.” The word for “work,” itzavon, is the same word used in God’s statement to the man (Genesis 3:17–19): men will experience unending toil (itzavon). The usual translation (“pangs” or “pain”) is far less accurate. In addition to toil, the woman will experience more pregnancies; the Hebrew word is pregnancy, not childbearing, as most translations have it. Women, in other words, must have many children. They also must work hard, which is what the next clause also proclaims. The verse is a mandate for intense productive and reproductive roles for women; it sanctions what life meant for Israelite women. Women will bear children, and both women and men will toil as partners (ezer k’negdo) in household life.

In light of this, the notion of general male dominance in the second half of the verse is a distortion. More likely, the idea of male “rule” is related to the multiple pregnancies mentioned in the first half of the verse. A woman might resist repeated pregnancies because of the dangers of death in childbirth, but because she will “turn” (teshuqah, 3:16, rather than “desire” or “urge” as in many translations) toward her partner she will be sexually re-joined to him (Gen 2:23–24). Male rule in this verse is narrowly drawn, relating only to sexuality; male interpretive traditions have extended that idea by claiming that it means general male dominance.

Archetypes and Etiologies

The riveting and controversial story of human origins can best be understood as portraying archetypal human qualities, whereby the first humans represent all humans. The woman’s name Eve (ḥawwah) is probably derived from a root meaning “to live.” The introduction of her name is followed by a folk etymology; she is “mother of all living”. Her name is rich in symbolism, characterizing her archetypal role: as the first woman, Eve represents the essential life-giving maternal function of women. Archetypal maternal authority is also implied in her role as name-giver of the first human child. Eve is also the one who provides the first morsel of food in a narrative in which the words for “food” and “eat” (from the same Hebrew root, ’khl) appear repeatedly. The repetition of these words in the story of human origins reflects the Israelite concern with sustenance in the difficult environment of the Canaanite highlands. Eve’s action in handing the man some fruit may thus derive from the reality of women’s roles in food preparation rather than as a depiction of temptation or seduction.

The Eden story also serves etiological purposes. It helped ancient Israelites deal with the harsh realities of daily existence in the Iron Age (ca. 1200–586 BCE), especially in contrast with life in the more fertile and better watered areas of the ancient Near East, by providing an “explanation” for their difficult life conditions. The punitive statements addressed to the first couple prior to the expulsion from the garden depict the realities they will face.

Mother Eve

Eve does not disappear from the biblical story at the expulsion from the garden. In a little-noticed introduction (Genesis 4:1–2a) to the ensuing Cain and Abel narrative, Eve is said to have “created a man together with the Lord.” Typical translations—NRSV “produced a man with the help of the Lord”; NJPS “gained a male child with the help of the Lord”—obscure the highly unusual language. The word for “create” is the same as the word used in the Bible for the creative power of God (Genesis 14:19, 22) and in extrabiblical texts for the creativity of the Semitic mother goddess Asherah. Women in the Bible are otherwise said to “bear children,” not “create a man”; and creating a man “with” God links Eve’s creative power with that of God. Moreover, name giving is almost always a mother’s act in the Bible; it signifies authority over offspring, and it appears in Eve’s naming of Cain. Eve is last mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in more conventional notices of motherhood—when she bears her ill-fated second son Abel (Genesis 4:2a) and her third son Seth (Genesis 4:23).

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.