Em and Bat Rav Hisda are portrayed as trusted figures who offer wise counsel. The maidservant of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi while unnamed, is similarly depicted as the pinnacle of a wise woman. In contrast, Homa and Hova are mentioned in stories that caution the reader about the dangers of the killer-wife or the risk of allowing a wife to make halakhic decisions, respectively. Likewise, Judith is described as a warning against the practice of not obliging women to procreate. Ultimately, the women’s stories are used to supplement the narratives about the men around them.

Em (Fourth century CE)

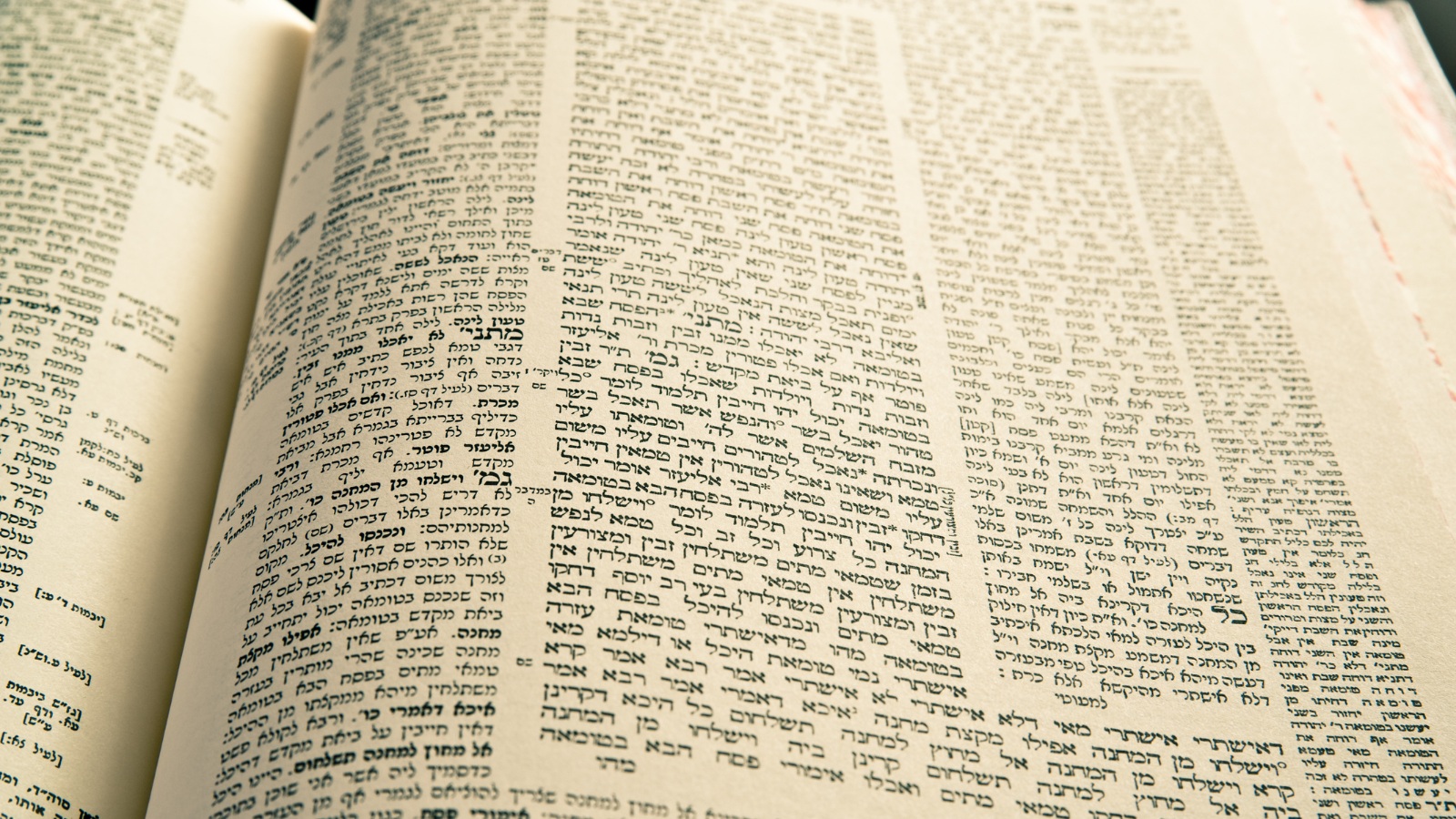

Em is mentioned in no fewer than 17 separate incidents in the Babylonian Talmud (of which only one is parallel to another). She is always mentioned in exactly the same formula: a rabbi states: “Em said to me” and these words are followed by useful, thoughtful and authoritative advice, which is never disputed.

Because in 14 of these traditions the person who quotes her is the fourth-century Babylonian amora Abbaye (278–338), it is usually assumed in scholarly circles that she was his mother, and that Em is a description (mother), rather than a name. The Babylonian Talmud itself already voices this explanation. The editors of the Talmud, however, knew that this woman could not have been Abbaye’s mother, since according to another tradition, his mother had died while giving birth to him (Kiddushin 31b). They solved the contradiction by assuming that the woman in question was his adoptive mother.

However, one tradition in the Babylonian Talmud suggests that when a sage quotes his mother he does not say “(a) mother said to me” but rather “my mother said to me” (Pesachim 112a). Furthermore, one other rabbi, aside from Abbaye, his late contemporary Ravina (the editor of the Talmud) is also mentioned as quoting Em authoritatively in the same way (Berakhot 39b; Menachot 68b). This suggests that Em was perhaps a famous, authoritative woman known to the rabbis of Babylonia.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

It is therefore interesting to note what is the source of her authority. In one tradition she explains the nature of gossip (Moed Katan 12b). In another she shows expertise in amulets (Shabbat 66b). But in most other traditions she is an expert on folk remedies and diets (e.g. Eruvin 29b; Ketubot 10b; Gittin 67b; 70a; Avodah Zarah 28b). In most of these she specializes in the welfare of children and their growth. One set of traditions preserved in her name is a compendium of information relevant to the circumcision wound (Shabbat 133b–134a). In another place she advises about the age from which a child is able to fast on the festivals (Yoma 78b). This knowledge in pediatrics allows her to also make halakhic recommendations regarding children. In Ketubot 50a we read:

“Said Abbaye: Em said to me: At the age of six [a boy is fit] for Scripture [study], at the age of ten for Mishnah [study] and at the age of thirteen for fasts once in a while. And a girl [is ready] at the age of twelve.”

This is an extremely weighty halakhic decision and it is surprising to find the rabbis depending for it on this woman’s advice. Nevertheless, gossip, amulets, folk medicine, and the raising of children are traditional women’s occupations, and it is exactly in these areas that we find Em’s advice undisputed.

It therefore seems that Em must have been an impressive Jewish woman in Babylonia, a physician with a great reputation, who gained the rabbis’ confidence and trust to a very high degree.

Homa (fourth century CE)

Homa is mentioned in two traditions in the Babylonian Talmud. In Yevamot 64b she is described as being of a distinguished lineage: she is the daughter of Rav Isi, son of Rav Isaac son of Rav Yehudah. She is also described as the widow of Rehava of Pumbedita and Rav Isaac son of Rabbah bar bar Hannah. All are distinguished Babylonian rabbis. A third rabbi, Abbaye (fourth-century CE Babylonian Amora, see above), decides to marry her despite her fatal record as a wife and also promptly dies.

Thus, in this tradition she is described as the ultimate representation of the Killer Wife, who when twice widowed should not marry again (Tosefta Shabbat 15:8). This representation is further substantiated by the second appearance of Homa in the Babylonian Talmud. In Ketubot 65a she is presented as coming to court after being widowed in order to demand a wine allowance. She is then chased out of town by the judge’s wife (Bat Rav Hisda—see below), who claims that she is attempting to entice a fourth man (Bat Rav Hisda’s husband) into her deadly snares. The two stories are a demonstration of the fear Jewish society in Babylonia conceived of “killer wives,” and the unsympathetic treatment these victims of fortune underwent within that society.

Hova (third century CE)

Hova is mentioned twice by name in the Babylonian Talmud, in both cases in very similar circumstance. In the middle of a discussion of a halakhic issue (shaving young children—Nazir 57b; raising unclean animals—Bava Kamma 80a), Rav Ada bar Ahava asks Rav Huna what he thinks on the issue, to which he responds that he leaves this to Hova. The former retorts with a curse: May Hova bury her sons. We are then informed that Rav Huna had no children as long as Rav Ada bar Ahava was alive.

This conversation suggests that Hova was Rav Huna’s wife. Rav Huna was an important Babylonian sage of the third century. Both traditions are so similar that they clearly hint at a common editorial reworking. In either case the message is similar: rabbis who let their wives decide on halakhic matters should be severely punished.

Judith (second century CE)

Judith appears by name in only one tradition (Yevamot 65b; cf. Kiddushin 12b). We are informed that she was the wife of Rabbi Hiyya, a Babylonian sage who migrated to Eretz Israel at the time of Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi (end of second, beginning of third century CE) and raised his family there. We may therefore speculate that she was a native of the Land of Israel.

We are further informed that Judith bore her husband two pairs of twins and suffered much in labor. She then decided to refrain from further childbirth. She dressed herself as a stranger and inquired of her husband whether women were obligated to procreate. When he maintained that they were not she drank a sterilization potion. When he discovered her ruse, he became depressed at the thought that he would now have no more children. This story is told by way of criticizing the rabbinic dictum that women are not obligated to procreate.

A nameless woman, identified as the wife of Rabbi Hiyya, appears in four further traditions in the Babylonian Talmud. In one tradition Rabbi Hiyya instructs her to give charity to beggars so that if her children ever come to a similar fate, they will be so treated by others (Shabbat 151b). Two further traditions deal with the festivals. In one we are informed that Rabbi Hiyya’s wife peels barley husks for her husband on the festival (Beitzah 13b) and in another her husband instructs her on how to deal with an oven tile that fell into the oven on that day (Beitzah 32b).

Perhaps the most famous tradition about her is the one in which we are told that even though she used to pester her husband, he would always bring her a little token. When asked to explain his kindness he expressed the idea that one should not expect more from a wife than to raise children and protect their men-folk from sinning with other women (Yevamot 63a). All these traditions are obviously intended to portray Rabbi Hiyya and add to his biography, rather than to portray his wife.

Bat Rav Hisda (fourth century CE)

A strange tradition in the Babylonian Talmud presents Rav Hisda, a fourth-century Babylonian amora, advising his daughters on the proper behavior of wives toward their husbands. Most of this advice pertains to behavior that may appear unseemly to the outside observer, and is intended to protect the husband’s good name through his wife’s proper sexual conduct (Shabbat 140b). We may assume that the two daughters to whom Rav Hisda addressed this speech were those who, according to Berakhot 44a, eventually married the two brother sages Rav Rami and Rav Ukba, the sons of Hamma.

One of these daughters is probably the one who later (after she was widowed?) married Rabbah. This conclusion can be inferred from another tradition. In Bava Batra 12b we are told that when still a child, sitting on her father’s lap, she met his two pupils, Rami bar Hamma and Rabbah. In answer to her father’s question as to which one she preferred to marry, she answered, “Both,” to which Rabbah replied: “And me last.” Although the story does not continue to state that this is indeed what happened, we may assume that it was composed because of the well-known fact that Rav Hisda’s daughter had been married to both of Rav Hisda’s prized students.

As a unique character, Bat Rav Hisda is presented only as Rabbah’s wife. Twice we are informed that Rabbah had great trust in her and made legal and juristic decisions based on her judgment. The expression used to convey this trust is unique and untranslatable (קים ליה בגווה). It appears only 12 times in the entire Talmud, suggesting that such informal and complete trust is quite remarkable. A demonstration of how influential Bat Rav Hisda was on her husband’s legal decisions is the following case: A woman comes to court in order to swear an oath. At this point Bat Rav Hisda warned her husband that this woman was known as a liar.

In light of this information, Rabbah decides to extract an oath from her opponent in court rather than from her. Sometime later, when he receives similar informal information from a well-known rabbi (Rav Papa), he does not act on it. The rabbi is deeply hurt at this mistrust and reminds Rabbah of his different reaction when he was similarly warned by his wife. Rabbah replied that he has a relationship of special trust with his wife, but not with this Rav Papa (Ketubot 85a).

As Rabbah’s wife, Bat Rav Hisda is mentioned in six more traditions. She intimately informs her husband how a woman feels when she loses her virginity (Ketubot 39b). She acts as a jealous wife when she suspects another woman (e.g., Homa—see above) of attempting to seduce her husband (Ketubot 65a). On two halakhic matters, she informs her husband of her father’s conduct on the question of the meat of a first-born (Chullin 44b) and is allowed by him to process meat as a sign of his trust (Chagigah 5a). And she is described as becoming physically sick in her husband’s absence (Shabbat 129a).

It appears that these stories were told in the Babylonian Talmud because the rabbis observed in awe the unique relationship of trust and intimacy that existed between the couple (compare the case of Rabbi Hiyya above). This would suggest that in the world of the rabbis such intimacy was the exception rather than the rule.

The Maidservant of Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi (second century CE)

In the Jerusalem Talmud one finds two references to a female slave of Rabbi (i.e., Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi, editor of the Mishnah). The first is a witty story, in which the maidservant bests a would-be rapist by undermining his assumptions about the halakhic similarity between slaves and beasts (Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 3:4). Another episode suggests that Rabbi’s maidservant spoke a good, rich Hebrew, as did all members of Rabbi’s household. Thus, she was able to explain to Rabbi’s students difficult biblical words, whose meaning eluded them (Jerusalem Talmud Megillah 2:2, Jerusalem Talmud Megillah 73a and also in Jerusalem Talmud Sheviit 9:1, 38c). It is not obvious from these stories that the same maidservant is intended in both cases.

It does seem, however, that for the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud, this maidservant fired the imagination. She is mentioned no less than eight times, in most cases in clear Babylonian inventions. For example, one tradition relates how Rabbi’s maidservant once declared a ban of excommunication on a man whom she observed beating his son. The rabbis duly observed this ban (Moed Katan 17a). This story makes Rabbi’s maidservant into a sort of rabbinic authority. Yet it is clearly a reworking of a story found in the Jerusalem Talmud about an anonymous maidservant who declared such a ban on a teacher beating a pupil. There is no indication that this ban was ever observed (Jerusalem Talmud Moed Katan 3:1, 81d).

Other examples of her importance are her role as a food taster in Rabbi’s household (Shabbat 152a), her actions serving as a legal exemplum for women’s ritual immersion (Niddah 66b) and a story which shows her great compassion for her suffering master on his deathbed (Ketubot 104a). One tradition uses Rabbi’s maidservant as a clear example of the fact that women can also engage in “wisdom language” (Eruvin 53b). Her gender role in this tradition is underscored by the fact that it is told in order to counter other stories demonstrating women’s stupidity. Ironically, the language she uses in this tradition is Aramaic rather than the Hebrew for which she became famous in the Jerusalem Talmud. In fact, it is interesting to note that in the Babylonian Talmud the female family member with whom Rabbi is most often associated is his maidservant.

In sum, it appears that a Hebrew-speaking maidservant, invented by the Jerusalem Talmud in order to demonstrate how thoroughly Hebraized the house of Rabbi was, fired the imagination of the Babylonians, who made her into a paradigm of feminine wisdom.

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.