The America that Jewish immigrants from Central Europe encountered [in the 19th century] when they disembarked in coastal port cities was in the throes of economic change. What had been, outside of a few port cities, a largely subsistence economy — consisting of small farms and tiny workshops that satisfied local needs through barter and exchange — gave way during the first half of the 19th century to a market-driven economy in which farmers and manufacturers produced food and goods that they shipped for cash to sometimes distant places.

Canals, turnpikes, and later railroad tracks linked far-separated points of the country, producing a vast national transportation network along which goods and commodities flowed.

Jewish Peddlers

The result was what historians call a market revolution. Entrepreneurial values coupled with new economic and cultural resources enabled people “to make choices on a scale previously unparalleled: choices of goods to consume, choices of occupations to follow educational choices, choices of lifestyles and identities.” As we shall see, the market revolution also profoundly shaped the lives of America’s growing community of Jews. They too now made choices on a scale previously unparalleled, ones that affected their patterns of settlement, their occupational preferences, their values and attitudes, and the practices of their faith.

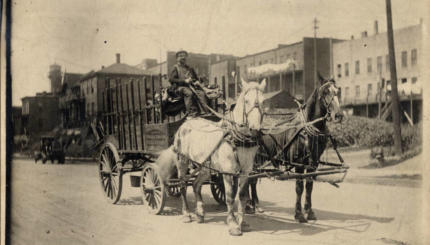

Peddlers were the foot soldiers of this far-reaching revolution. They were the proverbial middlemen who purchased goods (usually on credit) from producers and set forth to transport and market them to far-flung consumers, residents of America’s rapidly expanding frontier. Peddling was a difficult and tiring occupation, but it required very little capital and promised substantial returns.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

As the desire for goods rose among those who once found most of what they needed close to home but now pined for luxuries from faraway places, young, vigorous, success-minded immigrants rushed in to meet the burgeoning demand. Many of these immigrants — indeed, most of the 16,000 peddlers listed by the 1860 census-taker, according to one source — were Jews.

Peddling, of course, long predated the 19th century. The “Yankee peddler” was a familiar figure in 18th-century America, and Jewish peddlers roamed around Europe as early as the Middle Ages. For immigrants to America in the 19th century, however, peddling was less a career than a starting point; it served as the standard business apprenticeship for able-bodied young male Jews (Jewish women almost never engaged in peddling) looking to ascend the economic ladder to success.

Coming to America in their late teens or early 20s, these young men spent one to five years selling notions, dry goods, secondhand clothing, cheap jewelry, and similar products as they learned English and accumulated capital. Then they moved on to something better. Some succeeded handsomely: Most of the great Jewish department store magnates began their lives as peddlers. and so did a large number of other Jewish businessmen.

One Success Story

A typical rags-to-riches story went as follows:

Philip Heidelbach… arrived in New York in 1837. A fellow Bavarian helped him invest all of his eight dollars in the small merchandise that bulged in a peddler’s pack. At the end of three months the eight dollars had grown to an unencumbered capital of $150. Heartened by this splendid return Heidelbach headed for the western country, peddling overland and stopping at farm houses by night, where for the standard charge of 25 cents he could obtain supper, lodging, and breakfast.

In the spring of that year Heidelbach arrived in Cincinnati. He peddled the country within a radius of 100 miles from the source of his supply of goods, frequently traveling through Union and Liberty counties in Indiana. Before the year was out Heidelbach accumulated a capital of 2,000 dollars. Stopping in Chillicothe to replenish his stock, Heidelbach met [Jacob] Seasongood and the two men, each 25 years old, formed a partnership They pooled their resources, and for the next two years labored at peddling.

In the spring of 1840, they opened a dry goods store at Front and Sycamore Streets in the heart of commercial Cincinnati under the firm name of Heidelbach and Seasongood. The new firm became a center for peddlers’ supplies at once, business expanded they branched into the retail clothing trade.

The majority of Jewish immigrants, of course, did not climb quite so high on the ladder to success. In Philip Heidelbach’s own city of Cincinnati, for example, just over a third of a sample group of Jewish peddlers in the early 1840s moved up into more sedentary professions within three years; the other two-thirds took longer. A great many peddlers never rose above the level of small-town shopkeeper. An undetermined number failed completely: Some committed suicide, others lived out lives of penury, a few returned, disappointed, to Europe.

Frontier Judaism

Yet however they ultimately fared, this army of Central European Jewish immigrant peddlers transformed American Jewish life. As they fanned out across the country, spreading the fruits of American commerce to the hinterland, building up new markets for producers, and chasing after opportunities to get rich, they also carried Judaism to frontier settings where Jews had never been seen before.

By the Civil War, the number of organized Jewish communities with at least one established Jewish institution had reached 160, spread over 31 states and the District of Columbia (the 1860 U.S. Census listed synagogues in 19 of these states, plus the District of Columbia). Jews spread through every region of the country, including the rapidly developing West. In the wake of the 1848-49 gold rush, there were some 19 Jewish communities and five permanent congregations in California alone.

Subscription lists printed in Jewish newspapers show that individual Jews, though not a sufficient number to form a community, also lived in more than 1,000 other American locations during this period, wherever rivers, roads, or railroad tracks took them. That these solitary Jews subscribed to a Jewish newspaper indicates that maintaining ties to their kin remained important to them.

Jews never distributed themselves evenly across the American landscape: Over a quarter of all the nation’s Jews in 1860 still lived in New York City. Still, the fact that as a group they had dispersed throughout the country by the Civil War remains deeply significant, securing Judaism’s position as a national American faith.

Adherents had voted with their feet (and their packs) neither to confine themselves to a few major port cities, as colonial Jews largely had done, nor to form Ararat-like enclaves [places reserved exclusively for Jews to live in], as proponents of Jewish colonies advocated and some other persecuted minority groups did. Instead, like the bulk of immigrants to America’s shores, Jews pursued opportunities wherever they found them. In so doing, simply by taking up residence in a prospective boomtown, they legitimated Judaism, winning it a place among the panoply of accepted local faiths.

Challenges of Dispersion

At the same time, however, dispersion also posed significant religious problems for Jews. Without a minyan [prayer quorum], communal worship could not take place. Nor could peddlers and frontier settlers, living apart from their fellow Jews, easily conform to the rhythm of Jewish life, with its weekly Sabbath on Saturday and its holidays that fell on American workdays.

“God of Israel,” one such isolated peddler prayed into his diary in 1843, “Thou knowest my thoughts. Thou alone knowest my grief when, on the Sabbath’s eve, I must retire [alone] to my lodging and on Saturday morning carry my pack on my back, profaning the holy day, God’s gift to His people Israel. I can’t live as a Jew.” Another peddler kept careful track of his observances and calculated that over the course of three years he had been able to observe the Sabbath properly fewer than 10 times.

Settling down in a remote corner of the frontier did not necessarily make life easier. Joseph Jonas, the first permanent Jewish settler west of the Alleghenies and the founder of the Jewish community of Cincinnati, recalled that he remained “solitary and alone.. . for more than two years, and at the solemn festivals of our religion, in solitude was he obliged to commune with his Maker.”

Some frontier Jews, in the absence of any available Jewish worship, went so far as to attend Sunday church services, thereby reassuring Christian neighbors of their piety. But this was hardly a satisfactory solution. More commonly, isolated Jews looked forward to the arrival in town of other Jews, enough to establish a community.

Reprinted with permission from American Judaism: A History (Yale University Press).