ic Judaism is an Orthodox spiritual revivalist movement that emerged in Eastern Europe in the 18th century. Followers of Hasidic Judaism (known as Hasidim, or “pious ones”) drew heavily on the Jewish mystical tradition in seeking a direct experience of God through ecstatic prayer and other rituals conducted under the spiritual direction of a Rebbe, a charismatic leader sometimes also known as a , or righteous man. At the movement’s height in the 19th century, it is estimated that roughly half of Eastern European Jews were . The movement was decimated by the Holocaust, but dozens of Hasidic sects (or courts) exist today centered mainly in Israel and the New York metropolitan area.

Hasidic Judaism’s Beginnings

Hasidic Judaism first arose in Ukraine amid a wider resurgence of interest in Jewish mysticism and as an alternative to those who hewed to a more formal and scholarly approach to Jewish practice and would later become known as mitnagdim (literally “opponents”). Born circa 1700, the founder of Hasidism was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, better known as the Baal Shem Tov (literally “master of the good name”) and sometimes referred to by the Hebrew acronym the Besht. Little of the Baal Shem Tov’s biography has been firmly established by historians, but stories of his charismatic leadership and skills as a miracle worker became entrenched in Hasidic lore. Unlike the prominent rabbis of his day who were renowned for their Talmudic scholarship, the Baal Shem Tov worked as a schoolteacher and a laborer and was known to spend long stretches of time meditating and wandering in the woods.

The Baal Shem Tov traveled widely and developed a devoted following. Rather than lecturing on Jewish law, he urged his disciples to develop a personal relationship with God. Among his teachings was the importance of d’vekut (literally “adhesion”), a term referring to a mystical state of connection with God that could be achieved by unifying the spiritual and material realms. . Following his death in 1760, his teachings were further developed and disseminated by his disciples, chief among them Dov Ber of Mezritch, also known as the Maggid of Mezritch. Dov Ber attracted numerous disciples of his own, several of whom founded their own Hasidic dynasties. Among these were Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad sect, and Rabbi Aharon of Karlin, founder of the Karlin-Stolin dynasty. Another of the Baal Shem Tov’s followers, Rabbi Jacob Joseph of Polonne, authored the first Hasidic text, Toldos Yaacov Yosef, a major source of the Baal Shem Tov’s teachings.

Hasidic practices were distinct from mainstream Judaism in a number of ways. Hasidism brought Jewish mysticism to the masses, something that had traditionally been kept somewhat secret and restricted to a pious and learned few. It de-emphasized Jewish study in favor of Jewish practice, particularly prayer, and embraced a culture of folk tales that often had elements of magic and miracles. Hasidic Jews also rejected the traditional prayer standards and embraced a version that drew from both Ashkenazi and sources.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Opposition to Hasidic Judaism

By the late 18th century, Hasidism was spreading rapidly, evoking significant opposition from the so-called mitnagdim, who regarded Hasidic practices as essentially heretical, inconsistent with the rationalist Talmudic tradition and too reminiscent of the mystical ways of the Sabbateans, the movement begun in the 17th century by the false messiah Shabbetai Zevi. Among the most prominent early opponents of Hasidism was the Vilna Gaon, the revered leader of Lithuanian Jewry, who issued edicts of excommunication against the Hasidim but failed to halt their growth. The schism would not be fully put to rest until the founding of the ultra-Orthodox organization Agudath Israel in Poland in 1912, when the two sides set aside their differences in the interest of jointly battling secularism and Zionism. Today, both Hasidism and so-called Litvish (or “yeshivish”) Judaism are considered subsets of ultra-Orthodox, or haredi, Jewry.

Unique Hasidic Practices

Rebbes

Among the most unique features of Hasidic Judaism is the centrality of the Rebbe. Every Hasidic sect has one, and their succession over time is typically dynastic. When a rebbe dies, his successor is usually a son or other close relative. (The best-known Hasidic rebbe in modern times, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Chabad, was the son-in-law of the previous Chabad rebbe; Schneerson, who died childless in 1994, has not been succeeded.) Occasionally, succession can be contested and even split a sect, as happened in 2006 following the death of the Satmar Rebbe Moshe Teitelbaum. In Hasidic communities, the rebbe functions not merely as a communal leader and spiritual authority, but often holds an almost mythical status among his followers. Rebbes are commonly petitioned for help in situations of ill health or financial distress, their advice is sought on various personal matters, and they are often seen as something akin to a conduit to God.

Clothing

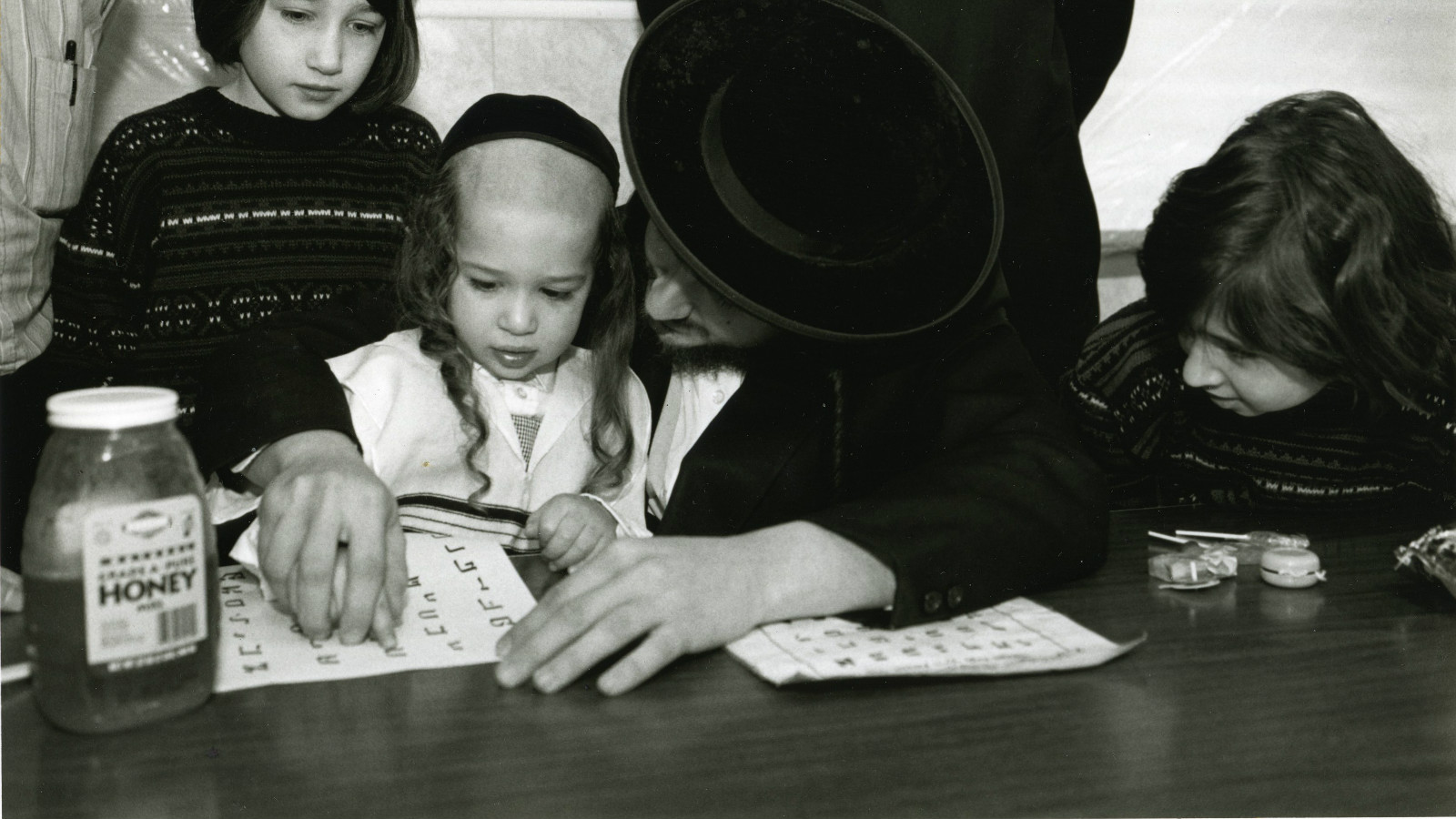

Another notable distinction among Hasidic Jews is their mode of dress. Though black outerwear and white shirts are standard for men and long-sleeved and high-necked clothing are typical for women, several groups have subtly distinct clothing for men identifying them as members of a particular Hasidic sect. Chabad men, for example, wear a black fedora-style hat. In other groups, the men wear a more elaborate fur-trimmed hat called a shtreimel or a spodik. (Some non-Hasidic ultra-Orthodox Jews also wear black hats.) Hasidic men typically wear a black overcoat known as a bekishe or a kapota. And in some groups, men wear distinctive white stockings. Most Hasidic groups still use Yiddish as their primary language.

Impact of the Holocaust

Before World War II, hundreds of Hasidic sects flourished in Eastern Europe, typically in small towns and villages whose names were eventually adopted as the name of the sects themselves: Bobov, Satmar, Ger and many others. The Holocaust hit Hasidic communities particularly hard — their clothing and other distinctive practices made it difficult for for them to hide from the Nazis, and many were reluctant to flee to the United States and pre-state Israel.

Those that survived the Holocaust re-established themselves outside of Eastern Europe, primarily in the New York area and in Israel, and many achieved something of a renaissance. Chabad in particular grew dramatically after World War II as it established its headquarters in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and dispatched emissaries across the world to reach out to unaffiliated and secular Jews. High birth rates in Hasidic communities, driven both by religious considerations and a desire to repopulate the community following the Holocaust, also contributed to their expansion. There are an estimated 400,000 Hasidic Jews in the world today. And in the New York area they represent 16 percent of the total Jewish population according to a 2011 study.