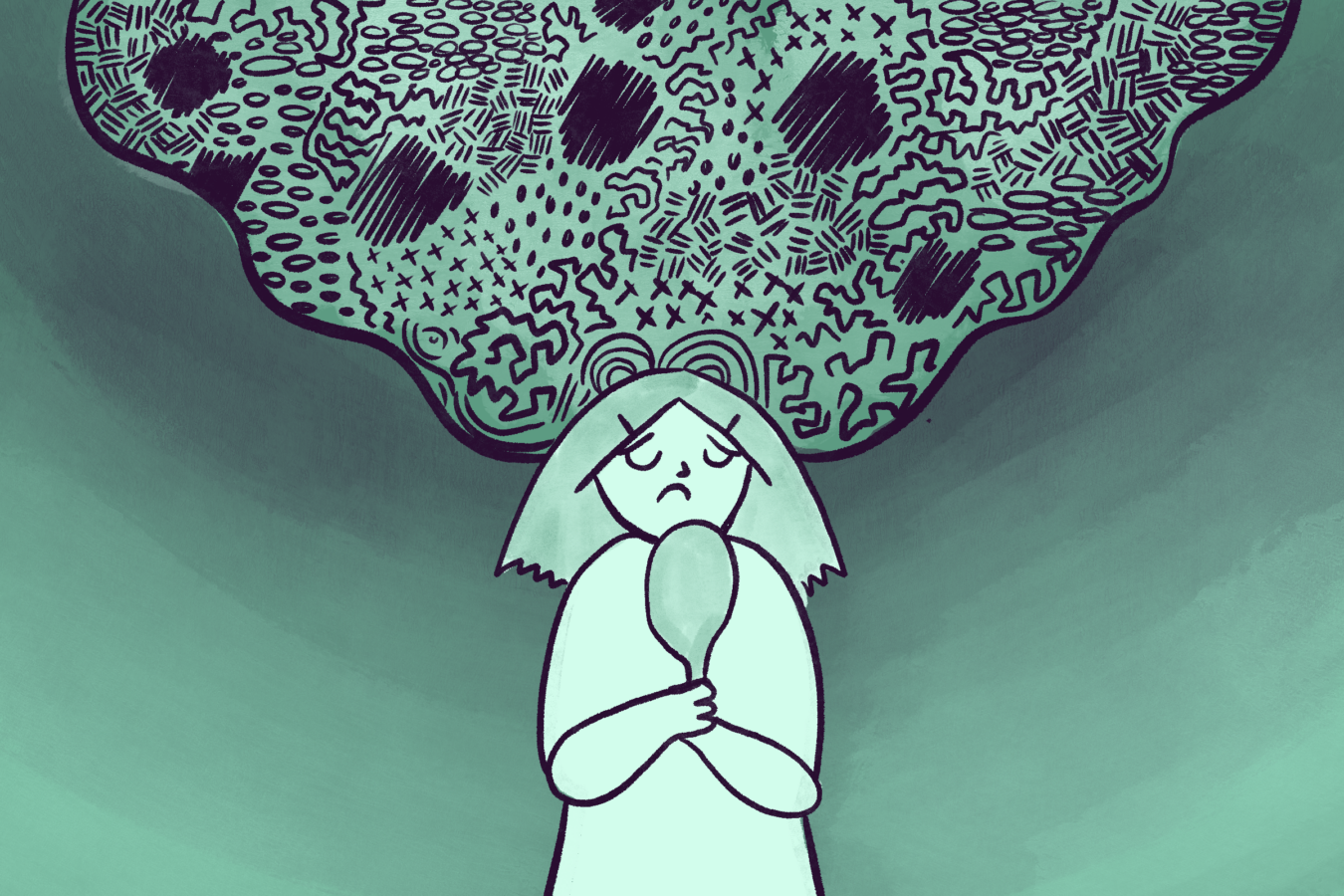

Everyone encounters demons of the soul. These can be strong or weak, at certain times more pressing and at others barely noticeable. Yet whether it is as mild as the discomfort of slight anxiety or as painful as feelings of worthlessness or depression, these experiences are shared aspects of human life. No one escapes them.

The Hasidic tradition applied the insights of Jewish mysticism to precisely these kinds of challenges, helping us discover paths to freedom from these states through rediscovering our genuine divine self. Two Hasidic practices in particular can help us work with these challenging states in ways that can be healing and transformative. These practices, like many Hasidic approaches, are grounded in the basic insight that everything is a manifestation of the divine, even our difficult experiences. It is through this switch of perspective — not understood intellectually, but felt in a concrete way — that liberation may be attained.

The practices described below are practices of both radical love and radical acceptance, a willingness to turn toward our suffering with open arms and a loving heart. Consistent practice and the guidance of an experienced teacher through a course or retreat will be very helpful for deepening in these techniques. But it’s possible to begin alone.

The first practice is based on one of the earliest Hasidic masters, Dov Baer of Mezritch (also known as the Maggid of Mezritch), who writes: “The principle is that all that a person sees and hears and all the occurrences which happen to him, they all come to awaken him.” The question is how we might use our experiences, even the difficult ones, as paths to awakening.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Our natural inclination is to push away unpleasant experiences. But the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, taught that, paradoxically, if we fight against these states, we simply feed them. The suffering worsens and we become more overwhelmed. Healing comes instead when we are willing to accept them and even extend compassion and love toward them. If, as the Hasidic masters claim, these experiences are in fact manifestations of divinity, then such acceptance and love may make a deep theological and psychological sense. Yet doing this, requires a willingness to look beneath the surface of the experience and cherish the deep spiritual need at its core.

We may be caught in anxiety, but we can turn to and love it when we understand it simply as a desire for safety. We may be caught in anger, but we can free ourselves from the trap of rage and recognize the wisdom it has to offer when we see that below the anger may be unresolved grief or fear. We may be caught in numbness, internally shutting down or using external aids to shut us off to the world, but with wisdom and patience we can come to understand this as another defense mechanism that, however painfully, is trying to keep us safe. Understanding, compassion, presence, and the ability to find our ground can help us safely move through numbness into vital engagement with life and the world.

The first practice is fairly direct, though not always easy. When a difficult emotional state arises, do the following:

- Stop.

- Pay attention to your body and allow it to feel grounded and connected to the floor.

- Notice if there is anything pleasant in your experience, any qualities you appreciate about yourself, or any beloved people in the world that might help you feel supported.

- Turn towards the difficult experience with as much compassion and love as possible.

- Ask yourself where you feel the experience in the body, while letting go of any story or narrative about the experience. Name the bodily sensations, their size, quality and texture. Rest your attention there.

- Invite that sensation in with as much love and compassion as possible. You are not inviting it in to take you over, but rather to have a hug, a cup of tea, or share a warm blanket. Try speaking to it with terms of endearment (“Come in, honey; “Come in, sweetie”). Or imagine it as a child, or any image that gives rise to care and compassion. Put your hand on your heart or on the place of tension in the body.

- Soften into the sensation, offering it love and healing on the outbreath as a kind of praying for that difficulty with your body.

The second technique, which involves shifting our understanding of ourselves, is based on a teaching by Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, also known as the Piaseczner Rebbe. Rabbi Shapira told a story of a prince sent by his father to bring a country of barbarians under control of the king. Yet rather than bring them under control, the prince is seduced by their ways, falling into robbing and stealing and committing all manner of harmful deeds. The king sent messengers to bring back his wayward son, yet their rebukes and even blows did nothing to reform him.

The king was troubled by all this, both by his son’s refusal and the harsh treatment he had received. As he began to lose hope, one of his advisers offered to try a different approach, one that wouldn’t rely on whips and lashes. Rather the advisor set about cleaning and restoring the prince’s palace. “All the candles and lamps will be lit, the silver and gold vessels will be polished, and the windows and doorways will be thrown open so that their light will shine from afar,” the adviser said. “Give me only a telescope.”

When the prince rebuffed the adviser’s entreaties, he was handed the telescope. “Please look at that room, and the light, and all the good that is prepared for you when you do what I command,” the adviser told him. When the prince saw the palace, a different spirit came over him. “What! I am a prince,” he exclaimed. “And before me is preserved and prepared such light, purity and brightness that I am almost blinded by the great light!” Through this realization, the prince was transformed.

Much like us, the prince got lost, forgot who he was, and began to act in ways that weren’t in alignment with his nature. And much like us, the prince was unmoved by criticism, shame, blows and judgment, all of which failed to transform him. But one wise counselor knew the prince could be transformed if he were able to again remember who he was. Similarly, when we are caught in painful feelings, we can transform by remembering what the Hasidic teachers understood to be our true nature — open, loving, good, luminous and divine.

This practice helps us see our divine nature and touch the openness, love and clarity that lies underneath our habitual patterns and challenging emotional states. The instructions are simple:

- Pay attention to your body and allow it to feel grounded and connected to the floor.

- Do any or all of the following to remind yourself of your basic goodness and luminosity (these practices are your telescope):

- Allow whatever pleasant feelings arise to permeate your body. Marinate in these feelings and allow yourself to feel the sense of support and clarity they bring.

- Recall a specific helpful action you have done.

- Bring to mind a quality you cherish in yourself.

- Picture a smiling baby and notice the natural delight and goodness it evokes.

- Think of someone who loves you and imagine then telling you who you are.

- Touch into your innate desire for openness, peace, happiness and joy.

- Consider the miracle of your existence and the specific circumstances that led to your creation.

- Remind yourself that you are held in God’s love.

- Allow whatever pleasant feelings arise to permeate your body. Marinate in these feelings and allow yourself to feel the sense of support and clarity they bring.

These practices of transformation can be practiced at any time and in any place. They can be taken as a formal practice, but they can also be used whenever necessary, sometimes for as little as a few seconds. For these ways of seeing ourselves to truly take hold and be transformational, we must practice them, and seeking out supportive communities of practice can be crucial to this work. Through concrete practice, these ways of seeing and relating to ourselves and the world can awaken us to who we truly are.