The Amidah, the core prayer of every Jewish worship service, consists of a series of nineteen blessings: three introductory blessings of praise, 13 blessings of petition and three blessings of thanks. On Shabbat and festivals, the middle 13 blessings of petition are omitted and replaced by one blessing that marks Shabbat or the holiday. Under some circumstances, even when it is an ordinary work day, one is allowed to substitute one long blessing for the 13 standalone petitions. This long, combined blessing is called Havinenu.

When Does One Say Havinenu?

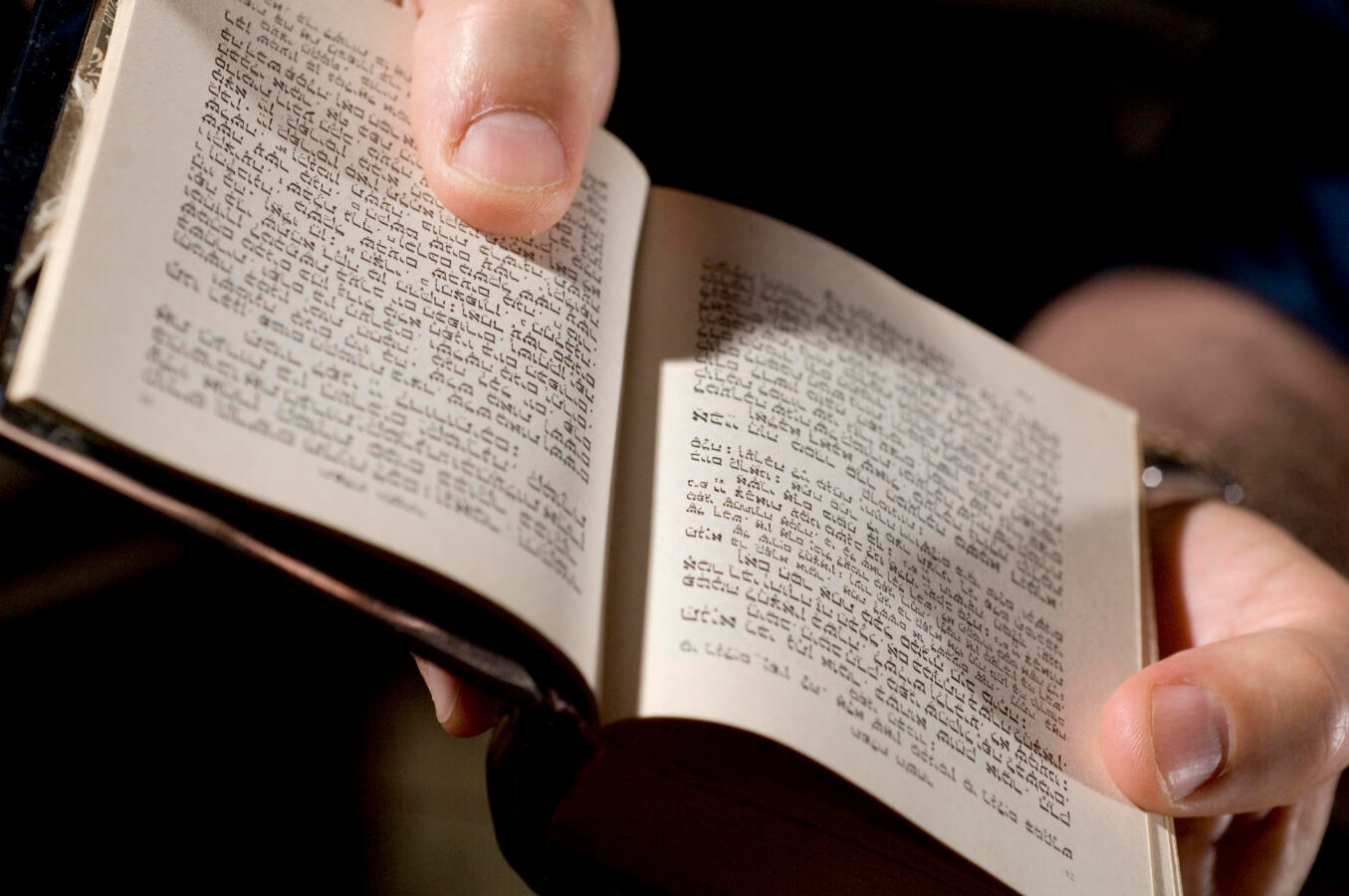

From the beginning, the sages disagreed about when it is permissible to use Havinenu to shorten the Amidah. In Mishnah Berakhot 4:3, Rabban Gamliel states that a person should never shorten the Amidah and always say the complete blessings in their entirety. Rabbi Yehoshua disagrees and holds that a person can say “a kind of Amidah” and still fulfill their prayer obligation. Rabbi Akiva then arrives at a compromise between the first two positions: One can say “a kind of Amidah” only in a situation in which that individual does not have the full Amidah “fluent in their mouth” — in other words, when they don’t yet know the words of the Amidah well. Since the rabbis of the Mishnah lived in a time when prayers were more spontaneous and there were no printed prayer books from which to recite the full Amidah, Havinenu allowed individual Jews who were not as fluent in the liturgy to nonetheless fulfill their obligation.

Generations later, the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud ask what Rabbi Yehoshua means when he allows for “a kind of Amidah.” Rav says he must be talking about an abridged version of each of the 13 middle blessings, but nonetheless a full set. Shmuel, on the other hand, suggests that Rabbi Yehoshua has in mind the Havinenu paragraph we know today, a single blessing that combines the themes of the 13 middle blessings of the Amidah.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

After the time of the Talmud, the circumstances under which someone could recite Havinenu were both broadened and limited. Maimonides writes that Havinenu is allowed for those who are not fluent in the Amidah and can also be used by someone who is distracted and would be unable to complete the full Amidah with the necessary concentration and focus. (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Prayer and the Priestly Blessing 2:2) In the words of the 13th-century rabbi, Menahem Meiri, it is better to be short in one’s words but have the proper intention than to say many words but not have the proper intention. In the Shulchan Aruch, Judaism’s premier law code, Rabbi Yosef Karo adds a few more categories of individuals who are permitted to use Havinenu. He writes that those who would be endangered or encumbered by spending a long time praying — for instance travelers on the road who worry about brigand attacks or laborers who are worried their pay may be docked — may substitute Havinenu for the 13 blessings of petition. (Shulchan Aruch, Orach Hayim, 110:1)

The Talmud (Berakhot 29a) records two times when one may not substitute Havinenu for the 13 separate blessings in the middle of the Amidah. First, during the evening prayer at the end of Shabbat or a festival. On those occasions, a Havdalah paragraph is added to the first of the middle blessings of the Amidah. Since one must say the full Havdalah paragraph, Havinenu is not an option. Second, one may not use Havinenu at all during the rainy season, when an additional request for rain from God is added to the sixth of the middle blessings of the Amidah. That request must be made as part of the full version of the sixth blessing, and thus from December until Passover, one is not allowed to say Havinenu.

In addition to these two restrictions, there is a strain of opposition to Havinenu in halakhic history. Already in the Talmud, Abaye is reported as having cursed those who used Havinenu, as opposed to the full Amidah (Berakhot 29a). Rabbi Isaac Alfasi, living in North Africa in the 11th century, limits the use of Havinenu only to exigent circumstances. This opinion is recorded as well by the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Hayim 110:1) and the Mishnah Berurah. Today, some prayer books do not even include the text of Havinenu (or it is included but not found in the table of contents).

Full Text of Havinenu

See below for one version of the Havinenu paragraph, which is taken from Shmuel’s statement in the Vilna edition of the Babylonian Talmud, and offered with the Koren-Steinsaltz translation. The Jerusalem Talmud also includes a version of Havinenu, but one that is quite different from the one found in the Babylonian Talmud (Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 4:3:15). In the many centuries since the closing of both Talmuds, different versions of Havinenu (with mostly small textual variations) have developed in different communities.

Havinenu consists of 13 short phrases, corresponding to the 13 original blessings of the Amidah, and a conclusion calling on God to hear the prayer:

הֲבִינֵנוּ ה׳ אֱלֹהֵינוּ לָדַעַת דְּרָכֶיךָ,

וּמוֹל אֶת לְבָבֵנוּ לְיִרְאָתֶךָ,

וְתִסְלַח לָנוּ לִהְיוֹת גְּאוּלִים,

וְרַחֲקֵנוּ מִמַּכְאוֹבֵינוּ,

וְדַשְּׁנֵנוּ בִּנְאוֹת אַרְצֶךָ,

וּנְפוּצוֹתֵינוּ מֵאַרְבַּע תְּקַבֵּץ,

וְהַתּוֹעִים עַל דַּעְתְּךָ יִשְׁפְּטוּ,

וְעַל הָרְשָׁעִים תָּנִיף יָדֶיךָ,

וְיִשְׂמְחוּ צַדִּיקִים בְּבִנְיַן עִירֶךָ

וּבְתִקּוּן הֵיכָלֶךָ,

וּבִצְמִיחַת קֶרֶן לְדָוִד עַבְדֶּךָ

וּבַעֲרִיכַת נֵר לְבֶן יִשַׁי מְשִׁיחֶךָ,

טֶרֶם נִקְרָא אַתָּה תַעֲנֶה.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה׳ שׁוֹמֵעַ תְּפִלָּה.

Havinenu Adonai Eloheinu la’da’at derachecha

U’mol et levaveinu le’yiratecha,

Ve’tislach lanu lehiot geulim,

Ve’rachakenu mi’machoveinu,

Ve’dashnenu bin’ot artzecha,

U’nefutzoteinu me’arbah tekabetz,

Ve’hato’im al da’at’cha yishpetu,

Ve’al reshaim tanif yadecha,

Ve’yishmechu tzadikkim bevinyan irecha

Uv’tikkun heichalecha,

Uv’tzmichat keren le’David avdecha

Uvarichat ner le’ven Yishai meshichecha.

Terem nikrah atah ta’a’neh.

Baruch atah Adonai, shome’a tefillah.

Grant us understanding, Lord our God, to know Your ways,

and sensitize our hearts so that we may revere You,

and forgive us so that we may be redeemed,

and keep us far from our suffering,

and satisfy us with the pastures of Your land,

and gather our scattered people from the four corners of the earth,

and those who go astray shall be judged according to Your will,

and raise Your hand against the wicked,

and may the righteous rejoice in the rebuilding of Your city

and the restoration of Your Sanctuary,

and in the flourishing of Your servant David,

and in establishing a light for Your Messiah, son of Yishai.

Before we call, may You answer.

Blessed are You, Lord, Who listens to prayer.

(Koren-Steinsaltz translation)

Conclusion

As we have seen, the use of Havinenu has a checkered history. Many are opposed to its broad use while others say it is an acceptable, perhaps even preferable substitution for the full Amidah when a person is unable to say it — either because of danger or lack of fluency. For those who are new to Jewish liturgy and just beginning their journey towards fluency, Havinenu can be a way to meditate on each theme of the Amidah, while its brevity allows the pray-er to focus on a smaller number of words.