Jews seldom study alone; the study of Torah is, more often than not, a social and even communal activity. Most commonly, Jews study Jewish texts in pairs, a method known as (“fellowship”). In havruta, the pair struggles to understand the meaning of each passage and discusses how to apply it to the larger issues addressed and even to their own lives. Sometimes they study to prepare for attending a lecture, and sometimes they meet to delve into a text independently of any organized class.

Often, a havruta chooses to learn in the beit midrash, a study hall, together with other havrutot. Together, havrutot (plural for havruta) create the atmosphere of the beit midrash where the sounds of discussion and debate fill the air.

How and why did study in havruta become such an integral part of the Jewish tradition? The Jewish tradition has always valued learning with others, whether with teachers or other students. Recent historical research, however, suggests that learning in pairs — havruta — only became the predominant mode of learning in the last century.

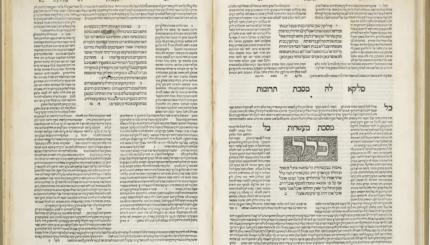

Some of the earliest references to learning in groups, and particularly in pairs, occur in the Talmud. The asserts that the Torah is only acquired in a group, haburah (Babylonian Talmud [BT], Berakhot63b). The word haburah derives from the same root as havruta — haver, or, in English, friend. The Talmud also particularly extols the value of learning in pairs: “Two scholars sharpen one another” (BT Ta’anit 7a)–two scholars, through discussion and debate, help to sharpen each other’s insight into the text.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The most frequently quoted saying in the Talmud relating to havruta is: “o havruta o mituta” (BT Ta’anit 23a), translated provocatively by Jacob Neusner as “Give me havruta or give me death.” Many Jewish scholars cite this phrase to illustrate the centrality of study in havruta. In context, however, the phrase has nothing to do with learning in pairs. Rather, the phrase means that the individual needs society and the respect of others, and without them life is not worth living. Still, the very fact that so many Jewish scholars take this phrase out of context and interpret it as referring to study in pairs shows the importance of havruta in the Jewish tradition.

Havruta in Medieval Sources

In addition to these Talmudic discussions, medieval Jewish commentators also address the benefits of study in havruta. Ovadiah Seforno, a 16th-century Italian rabbinic commentator, interprets the following verses in Ecclesiastes as referring to study in pairs:

Two are better off than one, in that they derive greater benefit from their efforts. For if they should fall, the one will raise up the other, as opposed to if one falls when there is no one to raise him. (Ecclesiastes 4:10-11)

He explains that two people learning together are better than one learning alone, because if one makes a mistake, the other will correct him, whereas if one learns alone there will be no one to correct him. Seforno’s interpretation does not emerge from the plain meaning of the text, which does not mention study, but his insistence on interpreting the verses in this creative manner shows the value he ascribes to study in pairs.

Don Yitzhak Abravanel, a 15th-century Spanish rabbinic commentator, discusses another benefit of havruta study. Abravanel interprets the saying “Make for yourself a rabbi and acquire for yourself a friend” (Mishnah Avot1:6) as meaning that one should learn both with a teacher and with another student. He explains that everyone has doubts at times or is confused regarding how to interpret the text. However, sometimes one is embarrassed to bring his questions to his rabbi. At these times, one can bring these questions to another student. Another student can clarify and sharpen one’s understanding of the text and can provide a different valuable perspective on that text.

The Emphasis on Havruta Is of Recent Vintage

Despite these early references to study in pairs, Shaul Stampfer, a contemporary Israeli historian, argues that study in havruta was not the prevailing mode of learning until the beginning of the last century. Even in the great 19th century yeshivot (Jewish academies of higher learning) of Eastern Europe, havruta was only one among many possible modes of study. These yeshivot sought to create a scholarly elite who would not need a havruta in order to understand the text. They saw havruta as only a means of helping weaker students who could not keep up with the class.

Yet today, study in havruta has become so widely accepted that two contemporary rabbinic scholars (Rabbi Menashe Klein in Mishneh Halakhot and Rabbi Shammai Gross in Shevet Kehati) address the question: If one cannot learn in havruta, should one learn at all? Although both rabbis answer in the affirmative, the fact that this question was even raised shows how predominant study in havruta has become.

How did study in havruta become so predominant in recent years? Stampfer, in an interview with Aliza Segal for her article “Havruta Study in the Contemporary h” (in Havruta Study: History, Benefits, and Enhancements, published by the Academy for Torah Initiatives and Directions), hypothesizes that study in havruta became predominant during the World War I period. At this time, yeshivot opened their doors to all Jewish men. Once yeshivot were no longer only for the elite, the students needed to learn in havruta in order to understand the difficult texts, and this mode of learning spread.

Today, learning in havruta is an integral part of traditional Jewish study. One yeshiva student sums up the importance of havruta:

It played a central role. You really needed it. To get the most out of a shiur (lecture) you had to prepare and review, because often, even the rebbe himself was very vague. It was very complicated stuff. If you tried to prepare by yourself, you’d be fooling yourself because you’d be limited by your own abilities. On the other hand, another’s viewpoint is always a little different and this way it would be much richer, almost like a third viewpoint, a combined result. As far as choosing a chavrusa [the word is a dialect variant of “havruta”] goes, it’s like choosing a wife. There are so many things involved. (from William B. Helmreich, The World of the Yeshiva, p.111)

Click here to sign up for A Daily Dose of Talmud, My Jewish Learning’s email series offering daily insights from the Talmud.

Yitzhak

Pronounced: eetz-KHAHK, Origin: Hebrew, Hebrew name for Isaac.