This commentary is provided by special arrangement with Canfei Nesharim. To learn more, visit www.canfeinesharim.org.

The

portion of Tazria discusses sickness and healing, concerning a person who contracts tzaraat (leprosy). In the case of tzaraat, what manifests as a physical symptom of the skin is not remedied through medical practice. The sick person does not see a doctor, though physicians are mentioned elsewhere in the Torah.

The

portion of Tazria discusses sickness and healing, concerning a person who contracts tzaraat (leprosy). In the case of tzaraat, what manifests as a physical symptom of the skin is not remedied through medical practice. The sick person does not see a doctor, though physicians are mentioned elsewhere in the Torah.

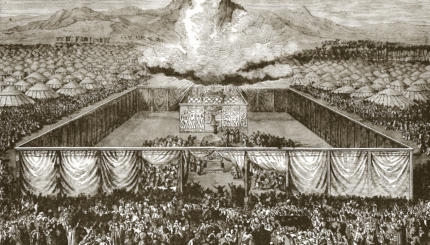

Instead a cohen, or priest, must diagnose the condition. The healing comes from a period of isolation, followed by immersion in a ritual bath and the bringing of an offering to the Temple. Through the depiction of a spiritual treatment to a physical ailment, this Torah portion presents a tremendous opportunity to connect to the roots of illness and come to true healing.

Physical & Spiritual Health

In the tradition of the Torah, physical well-being is inherently linked to spiritual balance. When a person is out of balance spiritually, he or she cannot be a vessel for Divine light, the flow of God-given life force which sustains all of existence.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The result is a physical manifestation of limited life energy, which appears as physical sickness, as in the case of the Torah’s description of tzaraat. The symbolic ritual process of healing which is described for one with tzaraat bypasses the physical aspect of the ailment and fixes the spiritual root of the problem.

The pinpoints seven spiritual sources of tzaraat, with one being a condition called “tzarut ayin,” or narrowness of vision (Shabbat 14a). Narrow vision means not paying attention to the wider ramifications of one’s actions. It is a decision-making process guided purely by the desire for immediate gratification, and not a larger plan to reach an extensive goal.

In this sense, tzarut ayin is the opposite of wisdom. Pirkei teaches, “Who is truly wise? One who foresees the result (Mishnah Avot 2:9).” In the Talmud, this is explained to mean: “One who understands what will come, events that will result, and is therefore wary of them (Tamid 32a).”

In the Torah, the skin blight that appears on the skin of the person with tzaraat is called a “nega.” There is a teaching that the difference between oneg (bliss) and nega (affliction) is the placement of the letter ayin. In Hebrew, the name of the letter ayin also is the word for eye.

With oneg, the ayin comes before the rest of the word, symbolizing foresight and ‘looking before one leaps.’ This is what leads to joy. Nega, however, has the ayin at the end of the word. This can teach that people come to low places because their vision only follows an action, and does not precede it.

Spiritual brokenness expresses itself in the physical world as in the case of tzaraat. Physical brokenness impairs one’s ability to make the proper spiritual choices. Just as a person has a body and a soul, this entire physical world is animated by the divine light of God that flows down from ever higher worlds.

On a Global Scale

Damage done in the natural world has traumatic effects on the spiritual world, and vice versa. This portion about the affliction of tzaraat can be understood in a global context: “Every person is a small world, and the world is a giant person (Rabbi Joseph Albo, Sefer Ha-ikarim).” In a macrocosmic sense, we can see the whole of humanity as one being, and apply the same lessons. Humanity today suffers from an illness, and the planet suffers as a result. The Torah offers a healing for this sickness.

The spiritual blemish of tzarut ayin, narrow vision, characterizes many environmentally unsound practices today. We live in a time when computers can calculate predictions of changes in organism population and ‘bioenergetics’. Certain scenarios of future development clearly point to a disastrous plunge in resources and thus human population.

The Jewish view of wisdom prohibits us from creating a situation where we will have major population crises, and we should have the foresight to prevent this. Otherwise, like the person with tzaraat, people will not experience true oneg (bliss), only its distorted equivalent.

People’s priorities are out of balance in areas as major as energy sourcing and waste management. The search for cheap non fossil-fuel energy leads many countries to rely on nuclear power, which creates radioactive waste that persists for thousands of years.

The desire to immediately remove something unwanted from our narrow field of vision is what rationalizes the unsustainable use of land as garbage dumps. People have confused their priorities in life because the light is broken and the world is out of balance. Fixing the world requires people to re-focus their priorities.

Western environmentalism posits two main problems with environmental degradation. One, that we will harm ourselves by changing the climate and polluting the air and water. The second, that we will run out of resources and then we will not have more to use. For example, although reducing energy use is an important goal of many environmental campaigns, getting people to simply “reduce” is more easily said than done.

Use of all forms of energy and electricity sources in America have increased steadily since the 1980’s, and continue to rise. For this reason, modern environmentalism champions the search for “alternative energy sources.” This approach tries to fix the brokenness without changing human lifestyles.

Consciousness Change

While technical approaches to current problems are important, consciousness change will also be necessary for true tikkun (repair) to occur. Such an approach promises to restore balance to the spiritual worlds as well as the physical.

A more expansive spiritual perspective sees harming the physical world as damaging the spiritual world, because the physical world is an outgrowth of the spiritual worlds. Since the opposite of ‘narrow vision’ is ‘wider vision’, we must ask; how broadly can we expand our outlook?

Will we stop our foresight and discussions of ‘sustainability’ here in the physical realm? Or will we see beyond that as well to the spiritual dimensions we are disrupting and thus enable fixing of those worlds? Furthermore, how can we expand our vision to these worlds, and how do we go about fixing the ‘spiritual environment’? The answer is in the Torah.

In the Torah’s first description of the Garden of Eden, that idealized environment, humans were placed there “l’ovdah u’lshomrah,” to work and protect it (Genesis 2:5). But the trees in the Garden of Eden did not need pruning or irrigation. We learn instead that the direct object of ‘to protect it’ is Torah, which means spiritual pursuit and balance. By ‘protecting’ the Torah, one can find instruction for balanced living in the world.

Though the world is in a state of physical and spiritual imbalance, it is not the result of God’s mistake or neglect. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, in teaching about prayer, mentioned that within a process, something is always imbalanced.

At every stage of life, something is not in harmony. This is because imbalance leads to new growth. Imbalance of global climate change can lead us to a new awareness and responsibility to change the way we live. Spiritual imbalance and global ecological imbalance are opportunities for growth towards sustainability, spiritually as well as physically.

Suggested Action Items:

1.

Learn about Life Cycle Analysis to expand the way you understand products and resources you use: your impact on where they come from, how you use them, and where they will go when you are done with them.

2. When you think about your “ecological footprint” consider also your ‘spiritual footprint.’ Do you pray for yourself and for others? Do you pray for the general well-being of the planet? What spiritual imbalances within yourself need rectification?

3. Ground one aspect of your environmental approach in a mitzvah: For example, if you are conscientious about overusing resources, give (charity) in place of a material item you would have bought. Connecting to the Torah’s instructions for this physical world helps to bring the spiritual balance that protects the physical world.