Commentary on Parashat Vaetchanan, Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11

You who live secure

In your warm houses

Who return at evening to find

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider whether this is a man,

Who labors in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies at a yes or a no.

Consider whether this is a woman,

Without hair or name

With no more strength to remember

Eyes empty and womb cold

As a frog in winter.

Consider that this has been:

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them on your hearts

When you are in your house, when you walk on your way,

When you go to bed, when you rise.

Repeat them to your children.

Or may your house crumble,

Disease render you powerless,

Your offspring avert their faces from you.-“ ” by Primo Levi

Why Shema?

Primo Levi wrote this poem in the shadow of the Holocaust, but his vision is especially relevant in the context of contemporary global inequity. It challenges all who live in comfort while others subsist in privation. Why does he use the frame of the Shema to do so?

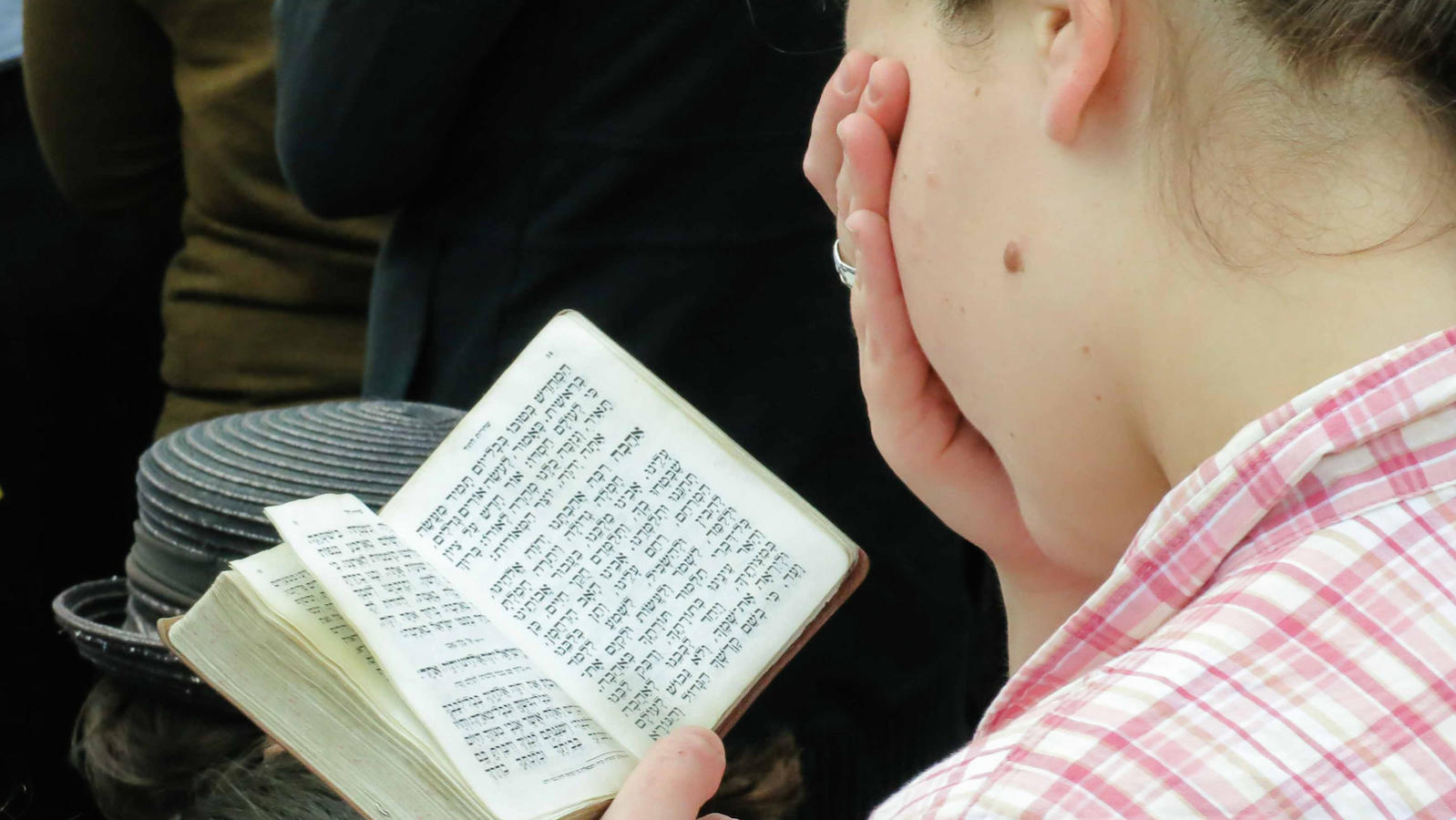

Found in the center of this week’s Torah portion, the Shema is a prayer declaring God’s singularity: “Listen, O Israel! The Lord is our God. The Lord is one (Deut. 6:4).” The Shema is repeated twice daily: in the morning and at night. It is often the first prayer taught to a child, and, famously, the Shema has been recited as the last words of many Jewish martyrs.

Primo Levi, in titling his poem “Shema,” attempts to redefine this traditional prayer. His poem commands a single-minded focus not on the unity of God but on a subset of God’s creatures, people living in poverty and chaos. Levi insists that human suffering is what our people should be “listening” to: as per the Shema, these sounds and images should be engraved on our hearts and follow us through our day. Effectively, they should be the frames of our experience.

Practically Speaking

How are we to hear this suffering? In one sense, it has never been easier. With the click of a mouse, one can access detailed information about any number of tragedies in the developing world. On the AJWS website, one can receive updates on Darfur, Zimbabwe, Burma and too many other countries experiencing crises of violence, poverty and disease.

But listening is not enough. The verb shema carries additional meanings — it also denotes doing, obeying, performing, acting. Perhaps Levi titled his poem “Shema” precisely for its multiple meanings. He wanted to jolt his reader, through graphic and painful images, into action. Emmanuel Levinas, a famous contemporary Jewish philosopher, described the traditional Shema as “an awakening: ‘Hear, Israel!'”

I read the poem’s upsetting closing curses as a contemporary warning: if we do not awaken, if we will not hear, if we do not use our blessings of privilege to improve the situation of those who suffer privation, we deny our own power to create change. There are serious consequences to this failure of action.

There are many ways to respond to the voices of those who suffer: to educate ourselves on issues of global justice, to volunteer, to advocate, to share our resources. The Shema, according to Jewish law, is supposed to be said aloud. It makes sense: we are crying out to one other: “Listen, Israel! Act!” This week, will you hear it?

Provided by special arrangement with American Jewish World Service. To learn more, visit www.ajws.org.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.