Reprinted with permission from

Modern Hebrew Literature in English Translation

, edited by Leon Yudkin.

This brings us to the preeminent subject of modern Hebrew literature during the period of the revival–the tension expressed between attachment to the old world and attraction to the new. These polar opposites took on different forms: geographical, historical, religious, cultural. The old world could be epitomized by loyalty and tradition, life in the shtetl, Yiddish speech, the East European environment. The new world could be the antithesis of these–loss of tradition, emigration, the Land of Israel, life permeated by rationalism and freedom.

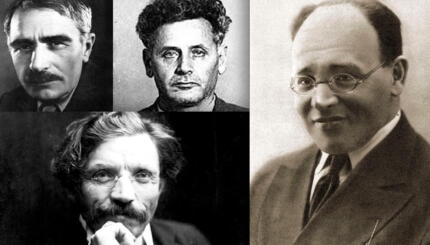

Expression of this tension with all its different features remains the theme and the mode of modern Hebrew literature. Both in the poetry of H.N. Bialik (1873-1934) and the fiction of S.Y. Agnon (1888‑1971), disparate subjects abound, but one theme predominates.

Bialik expresses the nation through himself, and himself through the nation. He mourns both, as in the poem “Al saf bet hamidrash” (1894), when he addresses the study‑house, repository of tradition, Jewish learning, and sentiment: “Should I weep for your destruction or for my own.” The study‑house is associatively equated with the Temple, whose destruction remains the focal reference point of Jewish history. And the destruction, via the depredation of the study‑house, now involves the poet in a consideration of his own disintegration.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

This is the sense in which Bialik genuinely assumes the role of the national poet, the way in which the national fate is subsumed in his own to the point of their merger. Agnon, too, throughout his work mourns the death of the old world, physical and spiritual, and implies the impossibility of its recovery, or a successful late return. Whereas the Haskalah [Enlightenment] literature had aspired to raise the Jewish standard and to address itself to the nation through the nation, Bialik and Agnon, like Uri Nissan Gnessin and Yoseph Hayim Brenner, addressed themselves to the individual through the individual, i.e., through themselves.

This is the sense in which Bialik genuinely assumes the role of the national poet, the way in which the national fate is subsumed in his own to the point of their merger. Agnon, too, throughout his work mourns the death of the old world, physical and spiritual, and implies the impossibility of its recovery, or a successful late return. Whereas the Haskalah [Enlightenment] literature had aspired to raise the Jewish standard and to address itself to the nation through the nation, Bialik and Agnon, like Uri Nissan Gnessin and Yoseph Hayim Brenner, addressed themselves to the individual through the individual, i.e., through themselves.

The work of Bialik and Agnon became a literary monument, an object of self‑identification for the masses, and the authors became known as national writers, however unpalatable the specific content of their work may have been. Both Bialik and Agnon are ambiguous. Such a great poem as “Megillat HaEsh” is obscure and threatening. The national aspirations of other poems take on weighty content, pregnant with danger. Works with a message fall far short of being clarion calls. As for Agnon, his hero is characteristically caught in indecision and failure, trapped between unworthy effort and elusive achievement. Neither Bialik nor Agnon offer an easy solution to the “Jewish problem,” and both seem, on the basis of the paraphrasable content of their work, to be unlikely candidates for the laureate. Clearly, however, the reader’s perception is different. This new Hebrew vision constitutes a complex vision of reality as yet unvoiced.