Hineni.

Here I am.

Most of what we recite in synagogue on the High Holidays utilizes the first person plural: We praise you. God, save us because we have sinned. We pray as a community and we express ourselves collectively.

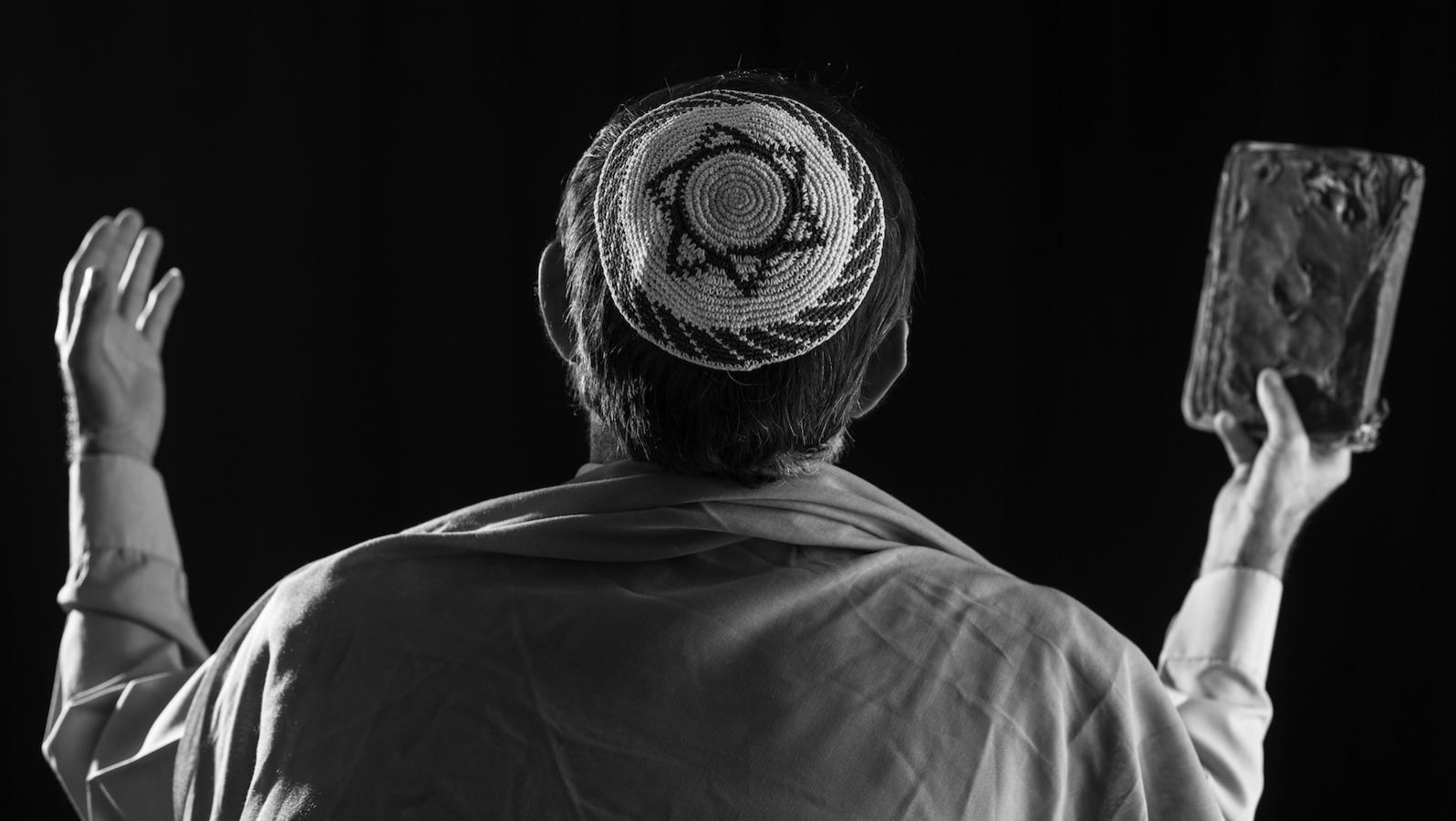

But the Hineni prayer, a meditation traditionally recited by the cantor prior to the Musaf (or additional) service on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, stands apart from the myriad pages of praise and supplication recited on the High Holidays in that it is worded in the first person singular. Curiously, the congregation seems to be but spectators to this moment of the liturgy. The cantor engages in a one-on-one dialogue with God, asking for his or her prayers to be received favorably, despite any personal shortcomings.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The cantor recites: Hineni he’ani mima’as. Here I am, impoverished in deeds and merit. But nevertheless I have come before You, God, to plead on behalf of Your people Israel.

Judaism teaches that each individual is responsible for his or her own prayer. Unlike other traditions, we do not recognize an intermediary. The cantor does not pray for us, but rather with us. The choreography and layout of the service bear this out. In a traditional sanctuary, the chazzan and the congregation face the same direction. Each worshipper is responsible for reciting each word of the text.

It therefore seems incongruous that on the High Holidays the cantor is functioning on behalf of the Jewish people. Furthermore, we worry that God might judge the congregation negatively because of the cantor’s transgressions. In some synagogues, the cantor chants Hineni while walking through the congregation, symbolizing that the congregation has literally sent the chazzan to lead the prayers on their behalf.

But in fact, the Hineni is really an expansion—a grand, dramatic version—of a type of prayer that we see every day in the Siddur. One example, often overlooked, appears before every instance of the Amidah:

Adonai, s’fatai tiftach, ufi yagid tehilatecha. God, open up my lips that my mouth may utter words of praise to you.

We recognize that just when we need to be the most focused and disciplined with our thoughts, it’s natural to fall short. We may not be in the moment. We may not be able to express the proper words. So we literally pray for the ability to pray.

All the more so is this true on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which according to traditional Jewish theology are literally life-or-death moments for the congregation. What if the cantor is distracted? What if all of the congregation’s prayers are rejected because of the deeds of one person? The cantor uses every tool at his disposal to enjoin God to look favorably upon him and the congregation.

The first word of the text —Hineni— is meant to remind God that He too shares some responsibility for what befalls the congregation. This one simple Hebrew word conveys millennia of Jewish transformation and acceptance of responsibility. Whenever a character in the Bible underwent a moment of profound change or crisis, he pronounced this same word: Hineni. Here I am.

When God called upon Abraham to sacrifice his son, Abraham answered, “Hineni.” When the angel of God later rushed to stop Abraham from performing this obscene act, Abraham once again said, “Hineni.” And when Moses stood before the burning bush and was called by name from within, he too responded, “Hineni.”

In these episodes, Abraham and Moses emerged transformed. And so it is with the chazzan on these most sacred days in the Jewish calendar. More than a simple indication of being physically present in a location, the word “Hineni” is more of an existential expression. I’m not only here, but I’m here. Spiritually, I’m all in. I’m prepared to reflect on who I am, what’s important to me, and how I can effect change for others.

One classic interpretation of dreams is that every character that appears in a dream is really you — that is, we project versions of ourselves throughout each dream. Similarly, the Hineni is not merely about the cantor engaging in a side conversation with God while the congregation looks on and waits.

Rather, when the chazzan states “Hineni,” it is in fact everyone present who are all saying the same thing, despite the prayer’s singular phrasing. We are here. It is we who are impoverished in spirit and deed, and we all share in the fear that our bad choices over the last year might be weighed against us. Nevertheless, we stand humble and ready for the difficult work of teshuvah (repentance) that lies ahead.

Cantor Matt Axelrod has served Congregation Beth Israel of Scotch Plains, New Jersey, since 1990. He is a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and a national officer of the Cantors Assembly. Cantor Axelrod is the author of Surviving Your Bar/Bat Mitzvah: The Ultimate Insider’s Guide, and Your Guide to the Jewish Holidays: From Shofar to Seder. You can read his blog at mattaxelrod.com.