The Seder Plate

In North African Jewish communities and in India, it was customary to pass the k’arah [seder plate] over the heads of everyone at the table in a circular motion. Encompassing all gathered in the historic experience. It was an acknowledgment that as the world turns, first we were slaves, then we became free.

Afikoman and Acting Out

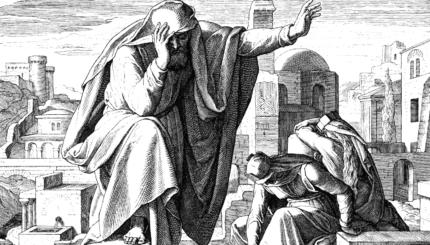

Many communities added dramatizations to their Exodus reenactment, usually of a Jew departing Egypt and wandering in exile expecting redemption.

Prior to the start of the seder in Djerba, Tunisia, young people come to pay their respects to the rabbi, some carrying sacks and staffs resting on their shoulders, hobo style. It used to be customary that when the middle matzah was broken during the service, a member of each household would be sent to neighbors to predict the messiah’s arrival.

In some Sephardic [Mediterranean Jewish] communities, the cloth-wrapped afikoman [the broken middle matzah that is hidden early in the seder] was tied to the shoulder of a child, who left the company and then reappeared knocking at the door. In the ensuing scripted dialogue, he identified himself as an Israelite on his way to Jerusalem carrying matzah. On entering the room, he looked at the specially arranged table and asked “Why is this night different from all other nights?”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Sometimes an adult walked around with the afikoman on his shoulder, as though it were bread carried on his back. One ofthe most elaborate of such ceremonies was dramatized in the Caucasus. The rabbi paced, like our ancestors leaving Egypt, with “their kneading troughs bound up in their clothes on their shoulders” (Exodus 12:34). The young men chose one person to portray a fugitive, dressed in rags, carrying the standard props. When he showed up at the door from Jerusalem to announce the coming redemption, the others did not readily believe him, until he cried, was invited in, and amid joyous celebration, answered questions about life in the Holy Land.

In Morocco, the enactment came at the end of the meal, when the participants quoted, “So you shall eat it: your loins girded…” (Exodus 12:11). Dramatizations extended to the synagogue also, where in some places in Eastern Europe, water was sprinkled on the floor during Shirah [reading about the parting of the Sea of Reeds in the Torah] on the seventh day. The people in the congregation took off their shoes to dip their toes into the water to experience the sea.

From the custom in Kurdistan ofbinding a ketubah (Jewish marriage contract) to the bride’s arm, the practice developed of tying the afikoman to the arm of a son the parents hoped would marry, wishing that the symbolic act would lead in the coming year to his binding a on his new bride’s arm.

Other folk beliefs surround the symbolic piece of cracker. In Asia, Iran, North Africa, and Greece, Jews kept a piece of the afikoman in their pockets or houses for good luck during the year, sometimes making a small hole in it so it could be hung like an amulet. Keeping the remains of the afikoman in rice, flour, and salt was thought by the Jews of Kurdistan to protect them against the depletion ofthese staples.

The Moroccans in particular believed this matzah had the power to safeguard them during ocean travel, and would throw it into the water to calm it in a storm. (They based the superstition on an appropriate verse from Psalms [54:9], whose first letters in Hebrew spell the word matzah.) Some believed that if kept for seven years, it could stop floods. Others attributed to it the capacity to stop fire and, when held in hand, to protect a woman and infant during childbirth.

Culinary Customs

Some Moroccan families would not eat black olives for the entire month of . They believed the fruit caused forgetfulness, and Nisan was the month in which the Jews were commanded to remember the Exodus. Calling the evening of seder Leil (Night) a/- Rosh (of the Heads), they customarily ate sheep heads in remembrance of the paschal sacrifice.

Excerpted from Celebrate! The Complete Jewish Holiday Handbook (Jason Aronson Inc). Reprinted with permission of the publisher.