My wife’s father, Nachum, was a force for life, energized by all sorts of human connection – be it dancing with an African-American woman at a South Los Angeles bike fest or drinking Turkish coffee with his Armenian neighbors. And then out of nowhere, at 67, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Months later, he was dead.

Our world lost light without my father-in-law. My wife, Talia, was shattered.

At first, the early Jewish rituals created some order for mourning. But as our pain did not end with the seven days of shiva, or the 30 days of shloshim, we needed to create a way to continue to mourn, and to find support, after those milestones had passed.

There was no daily prayer service in our area where my wife felt comfortable saying the Mourner’s Kaddish, as is traditional during the year following the death of a parent. Instead of her getting in the car each day to drive to the religious part of town, I suggested that we create a minyan of our own. And for a year, every Tuesday night, we welcomed friends, and sometimes mourners, looking for a place to pray, into our home. My wife led a prayer service for her father, shared reflections on loss and mourning, and then we broke bread.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The ritual was incredibly healing for us during a year when we were in desperate need of healing. Months after Nachum’s death, we lost my grandmother, and then Talia’s grandmother.

We were also witnessing changes in our country that impacted my wife directly: She is an immigration attorney and, while she had already spent countless days with clients trapped in detention, the new administration targeted the people she represents in new and terrifying ways.

Even as Talia returned to work at a feverish rate, there was a designated time each week to stop and reflect on her father, to feel the pain of his absence, and to connect with others in a very real way about topics we usually ignore. Generally, we gathered in our living room, but during the summer we sat outside and prayed as the stars appeared. In our Los Angeles neighborhood, once known as Red Hill for its critical mass of Communist residents, we followed my wife’s lead chanting the ancient songs.

Some of the people who joined us had also lost loved ones. Our mothers said Kaddish for their mothers. An Israeli couple we had recently met became among the most consistent minyan makers. We learned that both of them had also lost their fathers, and that this gathering provided an outlet to reflect on their losses like never before. It also was an opportunity to experiment with ritual different for both of them: The husband had grown up Orthodox, the wife secular.

Read More: The Best Foods to Bring to a Shiva

Others came simply to support us, and to connect with each other. Neighbors became friends. There was even a couple that met at of our Kaddish minyan. A year later, they are looking to move in together.

When, after a nearly year, we discovered that the time was up for Talia to say Kaddish, we ended our minyan, albeit reluctantly. It had become the most important ritual of our week. But it also was time for us to switch our focus from death to new life. Talia gave birth to twins weeks after the final Kaddish minyan. Our son is named Aviv Nachum after his saba. Our daughter Alma Pearl after her great-grandmothers.

Here’s how we created our Kaddish minyan, and steps to create your own.

1) We sought out the Jews in our area.

Our minyan count — that is, 10 Jews — was not strictly halachic. We weren’t opposed to non-Jews joining, but we wanted to make sure that Talia was not praying alone. We had ties to a local synagogue, a Jewish organization, and we had a circle of friends — all of whom received an email from us asking if anyone wanted to join us for a minyan (or many).

2) We created a Google sign-up sheet which we sent out weekly.

We did not always get to 10 on the sign-up sheet. Then we had to do some personalized emails and texts, entreating friends to show up. A few times we came up short, but generally we were able to hit 10. A few times we had almost 20.

3) We prayed.

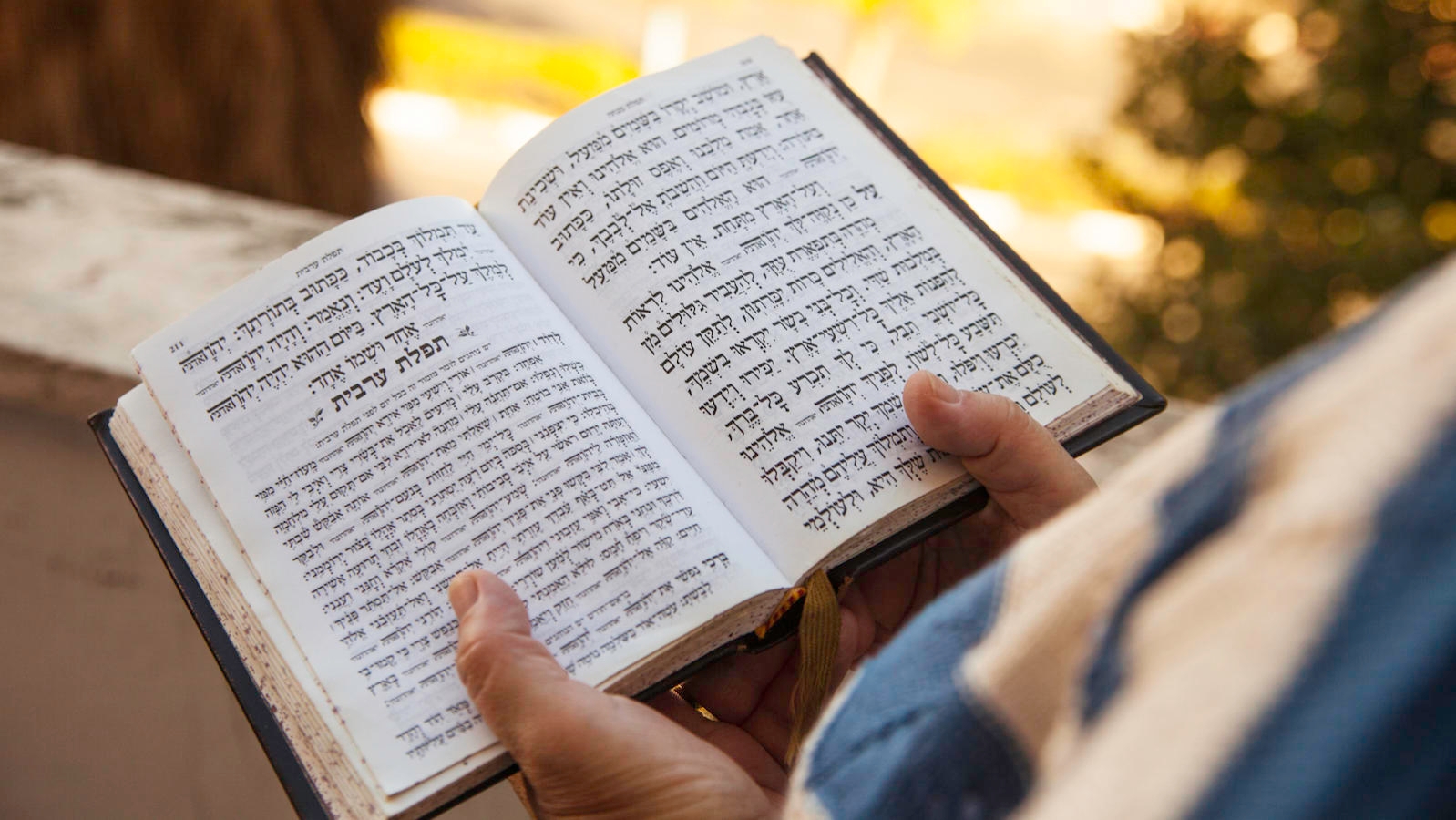

My wife knows how to lead prayers. I do not. She led a brief, beautiful Maariv (evening) service. Only a couple other people who came regularly could have done that. The rest of us learned a bit and followed along with prayer books the cemetery provided to us at the funeral. But I do not think you need to know how to lead prayers to hold a Kaddish minyan at your home. You could select one prayer, say the Sh’ma and the Mourner’s Kaddish. And if those do not work for you, you could create a short service of your own; it need not be in Hebrew.

4) We took a break to reflect.

In the middle of the service, my wife would pause and share a reading or thought. Toward the beginning of us doing these services, most of the reflections were drawn from reading she was doing about death and mourning rituals in Jewish tradition. She also wanted a chance to process and share stories about her father. My favorites of these were when after she would share her feelings about death, others in attendance would be moved to share about their own losses. Yes, it sometimes functioned a bit like a support group.

5) We included food (this is a Jewish ritual, after all).

This was not a shiva, but usually a few people in the group would bring something to share. We also would put out a simple, but inviting spread. For weeks, I made hummus, my Israeli father-in-law’s signature dish, and toasted lavash bread with olive oil and za’atar. One friend regularly brought samosas. Another brought home-baked bread. I think what also brought people back to our home, week after week, was that this was also a celebration of connection and friendship, even if we wished we had no reason to gather in the first place. My father-in-law would have approved.

(Daniela Gerson is an assistant professor of journalism at California State University, Northridge. She specializes in covering immigrant communities and participatory media, and is also a senior fellow at the Democracy Fund. Her first journalism job was with the Jewish Student Press Service.)

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.