Jews, particularly American ones, have a longstanding aversion to guns. According to a 2005 American Jewish Committee study, Jews have the lowest rate of gun ownership of all religious groups, with just 13 percent of Jewish households owning firearms (compared to 41 percent for non-Jews) and only 10 percent of Jews personally owning a gun (compared to 26 percent).

The majority of American Jews, who overwhelmingly live in urban rather than rural communities (where gun ownership tends to be more widespread) support the Democratic party, whose platform calls for stricter gun control, and major Jewish organizations have repeatedly thrown their support behind gun control measures. A 2013 list of prominent anti-gun activists compiled by the National Rifle Association included several of the largest Jewish groups.

Jewish gun groups, meanwhile, are few and far between, with limited influence. The most visible is Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership, based in Bellevue, Washington, which reported less than $100,000 in revenues in 2015 and lists only three board members on its IRS filing. Still, some Jews have long argued that the community’s broad opposition to firearms is naive and dangerous given the history of Jewish oppression and the persistence of anti-Semitism, sometimes violently expressed.

Is Jewish tradition in favor of gun control?

The debate over gun control policy, like most contemporary policy issues, has sources in the Jewish tradition to support both sides.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

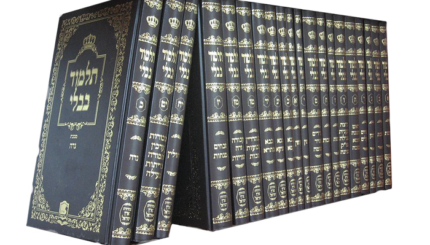

On the pro-gun side is the famous Talmudic dictum: If someone comes to kill you, rise up and kill him first. This statement from the Talmudic sage Rava is derived from a passage that permits a homeowner to kill an intruder in self-defense if the trespasser arrives in the night. Some Jewish gun proponents have argued that since the Torah commands self-preservation, acquiring the means for that preservation is also a religious requirement, with some going so far as to suggest that gun control laws prevent Jews from exercising their religious obligations.

Others have made the more pragmatic argument that in an era of heightened terrorist concerns, prudence dictates that Jews acquire firearms for self-defense — especially given that Jewish institutions are routinely targeted by Islamic and white supremacist terrorist groups. (Many institutions are, as a result, protected by security guards and other defensive measures.) Rabbi Dovid Bendory, sometimes known as the “gun rabbi,” has asserted that, given the history of Jewish oppression and the ongoing threats to Jewish institutions, Jews should be the first people in line to acquire defensive weaponry.

“How do Jews expect to put teeth behind the words “Never Again!” if not with the ability to apply and project personal force when righteous — and necessary — for survival?” Bendory wrote in an article on the JPFO website.

Jewish critics of the prevailing anti-gun sentiment within the Jewish community, have also noted the critical role guns and other weapons played for Jewish partisans — Jews who actively resisted the Nazis — during World War II, and later for Israelis fighting to establish and defend their state.

On the gun control side are a number of frequently cited rabbinic principles. Judaism mandates that one avoid unnecessary danger, and some studies show that gun ownership is risky. The Talmud in Avoda Zara prohibits selling weapons to idolaters, prompting one rabbinic authority to extend the ban even to Jewish bandits — a statement readily invoked to justify restricting gun sales to criminals and the mentally ill. Rabbinic groups from all three major Jewish denominations — Orthodox, Conservative and Reform — have all cited Jewish legal precedent in resolutions supporting gun control.

Finally, there’s the famous saying of Isaiah, who prophesied a time when nations would beat their swords into plough shares — a vision often said to reflect Judaism’s belief that the ideal society is one devoid of deadly weaponry. This dim view of weapons is cited in a Mishnah that records a disagreement over whether it is permitted to carry weapons on Shabbat. Rabbi Eliezer maintains that they are merely “ornaments,” but his colleagues, citing Isaiah, disagree, saying weapons are “indignities.”

The Orthodox Rabbinical Council of America, in its 2014 resolution in favor of restricting “American citizens’ easy and unregulated access to weapons,” cited Isaiah in support of its call for avoiding “recreational activities that desensitize participants to killing, weaponry, and violence.”

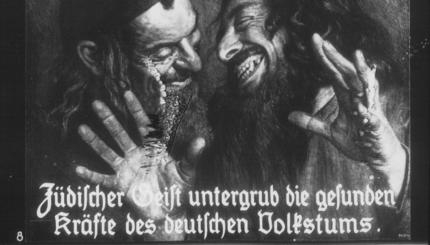

Didn’t gun control cause the Holocaust?

Some have suggested that if Jews had possessed guns in Nazi Germany, the Holocaust might not have occurred. Germany’s move to forbid Jewish gun ownership prior to launching the Final Solution is typically cited as a key support for this belief. Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson briefly made this notion a matter of public debate after including it in his 2015 book A More Perfect Union and in subsequent interviews. The Anti-Defamation League responded that it was ludicrous to suggest armed Jews could have stopped the Holocaust. (Carson called the ADL statement “foolishness.”)

But the argument has also surfaced in publicity materials from Jewish gun activists, including the 2010 documentary No Guns for Jews, which implied that gun control measures in Europe in the 1930s enabled the Nazi genocide. “When the right to self defense is denied, God’s law is violated,” the film intones. “Would history have been rewritten if the SS confronted thousands of armed Jews during the riots of Kristallnacht?”

Does Jewish law allow hunting?

Most authorities say it is not permissible to hunt for sport. Two sources are generally cited in this regard. The first is Rabbi Isaac Lampronri, who wrote in his work Pahad Yitzhak that it is forbidden to hunt animals because it’s wasteful. The 18th-century rabbinic authority Ezekiel Landau added that recreational hunting is forbidden on the grounds of animal cruelty and because of the risks to the hunter. Neither of the two biblical figures known to be hunters — Esau and Nimrod — are held up as role models. All the biblical patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac and Jacob), as well as Joseph, Moses and King David were herders — nurturers of animals, not their pursuers.

Hunting for food is, in principle, not objectionable. However land animals must be ritually slaughtered by hand to render them , which would make hunting them for food with a firearm impermissible.

Some American Jews do, nonetheless, hunt for sport. However, the American Jewish population is clustered in urban and suburban areas, where hunting is less pervasive than in rural areas.

Isn’t everyone in Israel armed?

Guns are highly visible in Israel. Soldiers toting large automatic weapons are ubiquitous in Israeli cities, and many sites and institutions are protected by armed security guards. In addition, some civilians carry sidearms, particularly in Jewish settlements in the West Bank. Supporters of looser gun laws in the United States have pointed to Israel as an example of a society made safer by the widespread availability of guns. Following the Sandy Hook elementary school massacre in 2012, National Rifle Association chief Wayne LaPierre claimed that Israel had ended school shootings by placing armed guards at every school. Israel said that claim was false and that there is “no comparison” between massacres by the mentally ill and those by ideologically driven terrorists. While most Israelis serve in the army, where they are trained to operate firearms, private gun ownership rates (not including military-issued weapons) are far lower in Israel than they are in the United States.

In fact, Israel has extensive restrictions on guns. Unlike the United States, Israel has no right to bear arms, and only certain groups of citizens are eligible to get a gun license — among them residents of West Bank settlements. Background checks, weapons training and demonstration of a bona fide reason for needing a gun are prerequisites for obtaining one. Maintaining a license requires completing regular courses in shooting and undergoing regular psychological evaluations. As many as 80 percent of Israel’s license requests are turned down annually.