Commentary on Parashat Tzav, Leviticus 6:1-8:36

While visiting my cousins to perform a naming ceremony for their new daughter, I somehow found myself explaining the sacrificial system described in Leviticus to her big brother, then age 5. We were in the living room, surrounded by friends and family and lots of food, following the naming ceremony, and he listened with fascination (and a few giggles) as I explained that thousands of years ago, we would have picked his family’s best goat or sheep and brought it to the local priest to show that we were grateful for his new little sister.

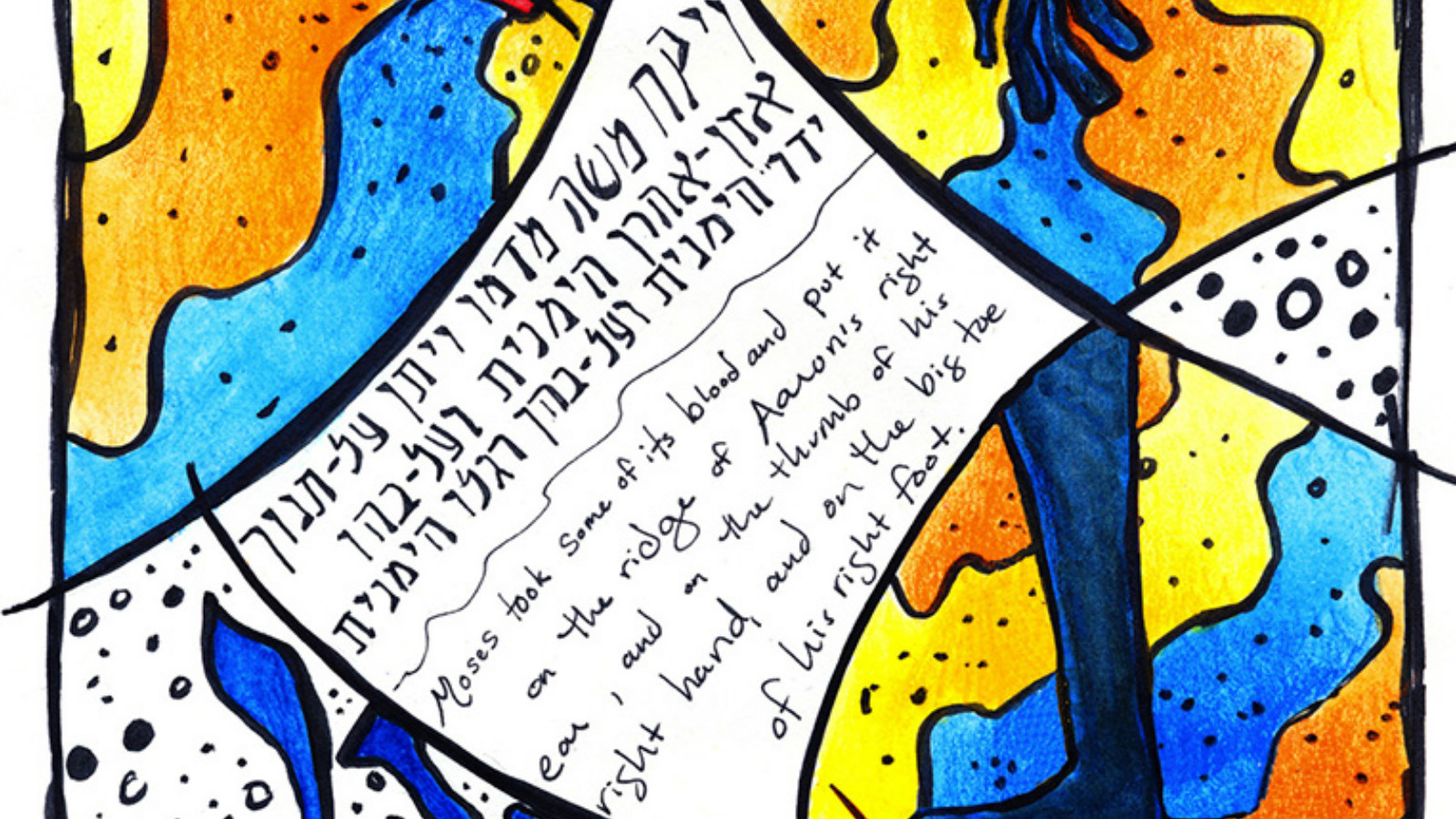

Reading this week’s Torah portion, Tzav, it may seem that the many different types of animal sacrifices being described have little or nothing to do with our lives in the 21st century. The sacrificial offerings described in Tzav include a priestly anointment offering, an offering for purification from sin, a guilt offering, a thanksgiving offering for well-being and a free-will offering.

Like our ancestors, we have a strong impulse to give thanks after the birth of a baby or after surviving a terrible accident. Many of us mark birthdays or weddings with charitable donations – free-will offerings. In synagogue communities, it’s common for the family of a new baby or a family observing the yahrzeit (anniversary of the death) of a family member to provide food for a community kiddush after a service. These rituals reflect the Temple sacrifices we read about in Leviticus, because the people who followed these laws had the same needs that we do: to draw strength from community, to mark life transitions publicly, to celebrate in times of joy, to be comforted in moments of sadness.

What about the “offering for purification from sin” and the “guilt offering?” These may sound strange or uncomfortable in our contemporary communities, where we avoid publicly noting the times when we’ve done something wrong, or something that feels shameful. I try to imagine bringing food for a communal meal and sharing the news that I’d had a terrible fight with my parents, and felt I had violated the commandment to honor one’s mother and father. It feels awkward just to think about it, and I can’t imagine trying it.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

But in Jewish tradition, asking forgiveness is a holy act. Struggling with the temptation to do something one knows is wrong and overcoming it is valued deeply. And once, many years ago, there were rituals that helped people share their struggles with their community, giving people the chance to make amends and have it seen publicly. Bringing a goat or a sheep and watching part of it burn to ash on the altar and part of it provide food for the priests may have given great satisfaction to those whose offerings were accepted, and communal forgiveness was granted.

I didn’t explain all of this to my 5-year-old cousin, but later in the afternoon, when play time got a little rough, he ran hard into my leg and knocked me down, and immediately flung his arms around me, saying, “Sowwy! I’m sowwy!” He kissed my knee and made it better, following another ritual that has been passed down for thousands of years. We do still need to have our moments of atonement recognized; we want our attempts to fix things to be seen. I’m not planning to bring a goat to barbecue the next time I ask someone for forgiveness, but I have learned from the ancient texts of Leviticus and from the very new wisdom of a 5-year-old that offering love and real contrition is no less holy.