Commentary on Parashat Vaetchanan, Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11

Moses continues to review the history of the Israelites from the time of their liberation from Egypt; he also repeatedly implores them to accept and faithfully follow the , stressing its goodness and wisdom. Moses warns the people not to worship any other god or power except the One God who gave them the Torah. Moses then reiterates the Ten Commandments. The paragraph which we know as the first paragraph of the Shema forms part of Moses’ exhortation to the people to keep faith with God after they enter the land, when Moses himself will no longer be able to guide or instruct them.

In Focus

“Know this day and set it upon your heart that is God — in heaven above and on earth below — there is no other.” (Deuteronomy 4:39)

Text

Moses delivers a long sermon to the people on the dangers of forgetting their experience of Liberation and Revelation — he warns them that they might fall into idolatry once they enter the land of Israel. He also promises that God will take them back, just as God took them out of Egypt to be a unique people. Moses urges the people to remember the giving of the Torah at Sinai and be mindful of God’s presence.

Commentary

The main point of Moses’ sermon seems fairly straightforward: Don’t forget about the God who liberated you once you settle in the Land. The verse above could therefore be a simple rhetorical device, employing extra phrases merely for emphasis of the basic point.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Read this way, there would be no substantial difference between “know this day” and “set it upon your heart” — they might mean basically the same thing, a steady consciousness of God’s existence, authority, and instructions. The next phrase, “in heaven above and on earth below,” could also be read this way, as complementary images which strengthen each other. Scholars of biblical rhetoric and poetry call this “parallelism,” from the idea that two parallel or similar images strengthen the rhetorical point but don’t really have two different meanings in themselves.

Traditional rabbinic Bible commentators, on the other hand, often like to read the text in more expansive and creative ways, perceiving new and additional meanings in each seemingly superfluous word. Thus Rabbi Israel Lipkin of Salant [popularly known as R. Israel Salanter], a 19th-century giant of Mussar [ethical development] teachings, sees “know this day” and “set it upon your heart” as two different stages in a process:

It is not sufficient merely to “know” it; this sublime knowledge must be taken into your very heart, so that your will and your virtues both should function in conformity with what you know. This task constitutes the entire service of a Jew. There is as much distance between “knowing” [something] and “setting it upon your heart” as there is between knowledge and ignorance.

[Quoted in Hebrew in Itturei Torah; this translation modified from the English Wellsprings of Torah]

R. Salanter draws an important distinction here: what we know only intellectually may not actually influence our behavior; this must come from a more integrated “knowing” of mind, heart, and soul. We might think of somebody with a bad habit, for example, who knows with their brain that their habit is self-destructive, yet cannot stop until they have really emotionally internalized their desire to change. I think R. Salanter is making the same point regarding the spiritual life: we can know something purely abstractly or intellectually, yet the challenge is to act at all times out of our spiritual convictions.

That’s a deeper, more holistic kind of spirituality; not merely believing something, but acting with great integrity, wherein one naturally behaves according to one’s own ideals. The great American preacher and civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King put it this way:

But we must remember that it’s possible to affirm the existence of God with your lips and deny [God’s] existence with your life. The most dangerous kind of atheism is not theoretical atheism, but practical atheism. And the world . . . is filled up with people who pay lip service to God but not life service. (A Knock at Midnight: The Great Sermons of Martin Luther King, p.15)

I am especially moved by Dr. King’s notion of “practical atheism;” this seems to me very close to what R.Salant is saying: While religious knowledge is a good thing, it’s not the same as leading a truly religious life. There’s a well known story, attributed in different places to different 19th-century rabbis, about a man who boasts that he’s been through the many times. “Fine,” replies the rabbi, “but how many times has the Talmud been through you?”

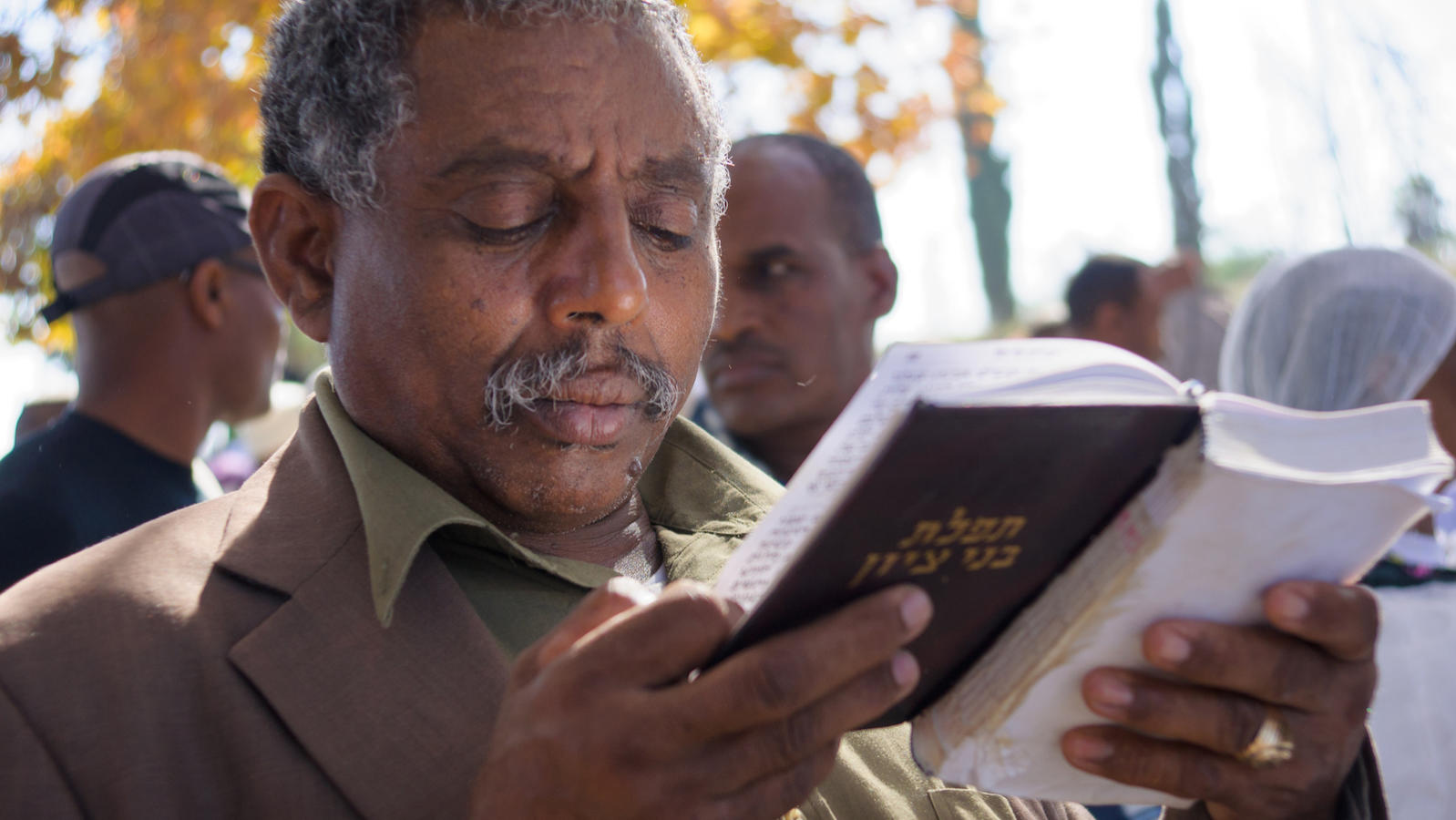

Striving for a wholeness, an integration, of mind, heart and soul — this is the “entire service” of a Jew.

Reprinted with permission from Kolel: The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning.