In the wake of the Holocaust, explicit anti-Semitism went into a kind of remission. The kind of nakedly anti-Jewish sentiment that had been so common prior to the genocide — images of Jews with hooked noses and greedy eyes; conspiracies about Jewish power and financial domination — became politically taboo, particularly in Europe.

As the consensus that such forms of anti-Semitism were beyond the pale took hold in the decades after World War II, a form of criticism of the State of Israel emerged that went beyond critique of particular Israeli actions or policies to attack the foundations and legitimacy of the state. Some began describing this as “the new anti-Semitism.”

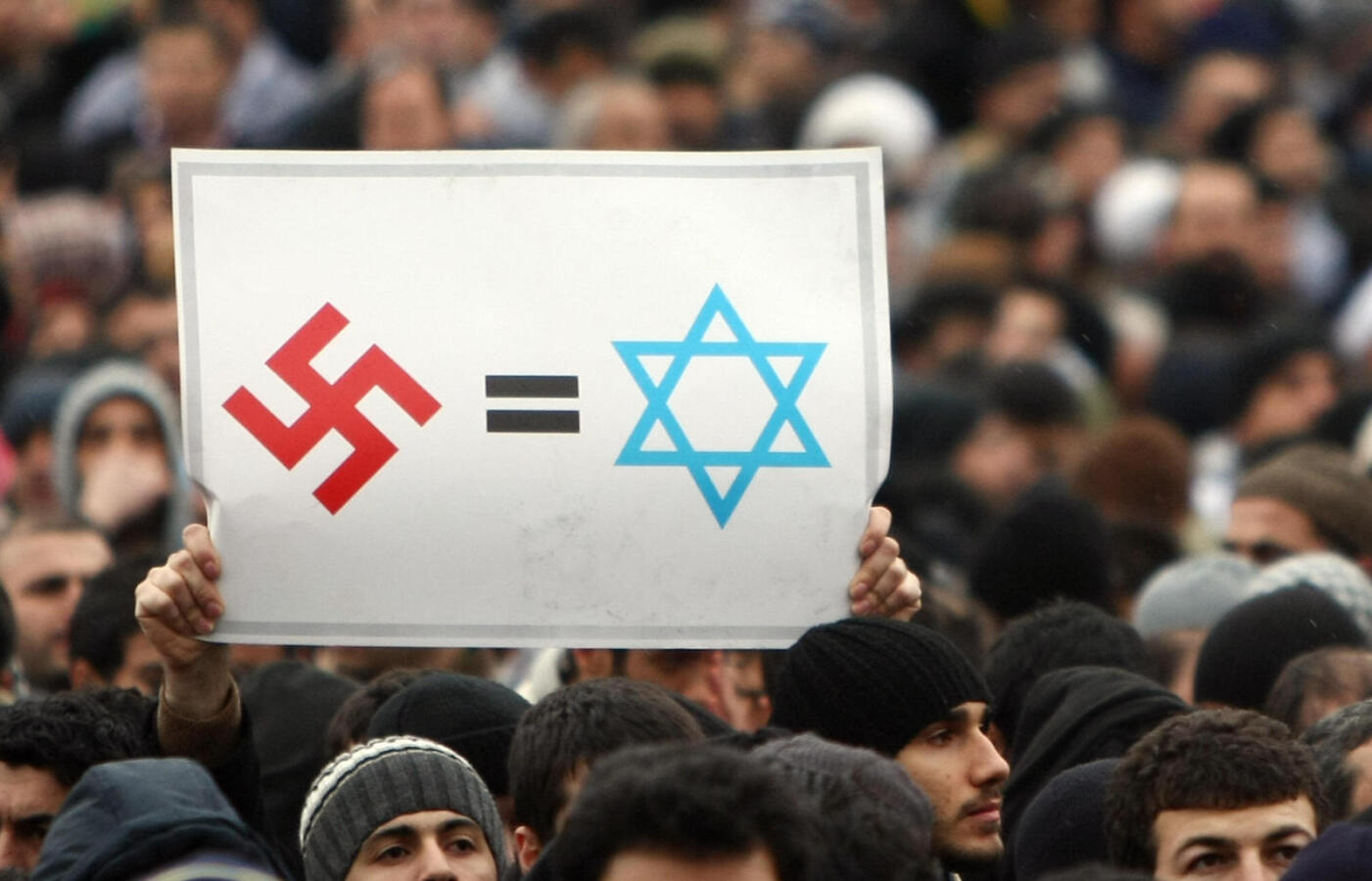

The notion that fierce criticism of Israel, even criticism that attacks the legitimacy of the state, is essentially anti-Semitic is a controversial one, and many reject it vehemently — Jews and Jewish groups among them. But the essence of the claim rests on the idea that opposing Zionism is the functional equivalent of denying the Jewish people the right accorded to most peoples of the world: the right to self-determination. As such, anti-Zionism is essentially anti-Semitic, even if it’s not motivated by explicit anti-Jewish animus. Examples of discourse that are commonly said to meet this standard include equating Israeli policy with that of the Nazis, demonizing Israel, describing Israel as racist, or denying Israel’s right to exist. Excessive criticism of Israel, characterizing it as a uniquely pernicious force in the world, or lambasting it for things that other countries do as well but with little protest, has also come to be regarded in some quarters as anti-Semitic.

To proponents of this idea, the replacement of “Jew” with “Israel” as the object of anti-Semitic discourse is emblematic of the shape-shifting nature of anti-Semitism. Just as anti-Semitism morphed as Europe secularized in the 19th century, from an idea rooted in Christian theology into one that saw Jews as racially distinct, the Holocaust had caused the virus of anti-Semitism to mutate once again, replacing antipathy toward Jews as individuals with opposition to the personification of Jewish power and nationhood: the State of Israel. With Israel’s establishment in 1948 — and particularly as it grew to become a regional superpower following the wars of 1967 and 1973 — centuries of anti-Semitic rhetoric about a secretive Jewish cabal that pulled the strings of world governance now had a visible and undeniably real manifestation of Jewish power to latch on to.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Among the earliest proponents of the idea that opposition to Israel’s existence constitutes a new form of an ancient hatred was Abba Eban, Israel’s foreign minister from 1966 to 1974. Writing in The New York Times a week before the United Nations adopted a resolution equating Zionism with racism in November 1975, Eban wrote: “There is, of course, no difference whatever between anti‐Semitism and the denial of Israel’s statehood. Classical anti‐Semitism denies the equal rights of Jews as citizens within society. Anti‐Zionism denies the equal rights of the Jewish people to its lawful sovereignty within the community of nations. The common principle in the two cases is discrimination.”

Eban’s op-ed, and the U.N. resolution that prompted it, came as Israel was transforming itself from a beleaguered democracy beset on all sides by enemy states into a regional superpower that had prevailed in two major wars within six years, tripling the land under its control in the process. The year before, two Anti-Defamation League staffers, Arnold Forster and Benjamin Epstein, published a book entitled “The New Anti-Semitism” in which they suggested that indifference to the possibility of Israel’s elimination was anti-Semitic. In 2003, a book of the same title by Phyllis Chesler went even further, calling Israel “the Jew of the world — scorned, scapegoated, demonized, and attacked.” Charges that Israel deliberately kills Palestinian children, Chesler wrote, were a modern-day blood libel.

As Israel’s relative power grew and Palestinian resistance exploded into sustained violence beginning in the 1980s, intense hostility toward Israel became a mainstay of left-wing discourse. By the turn of the millennium, many Jewish leaders were openly fretting that the entrenchment of anti-Israel sentiment on American campuses had created a hostile — that is, anti-Semitic — environment for Jewish students. The outbreak of the Second Palestinian Intifada in 2000, and the collapse of the once-promising Oslo peace process in the years that followed, further intensified global criticism of Israel — and cemented the idea that Israel was being held to an impossible standard. In 2006, Indiana University Professor Alvin Rosenfeld published a controversial essay claiming that progressive Jewish critics of Israel were fueling anti-Semitism by questioning Israel’s right to exist.

Natan Sharansky, the former Soviet dissident turned Israeli politician, has suggested three criteria that determine when legitimate criticism of Israel has veered into anti-Semitism: demonization, delegitimization, and double standard. Delegitimization implies that the existence of Israel is a racist endeavor or otherwise indicates that Israel is not a legitimate political entity. Demonization is the use of imagery or metaphors that portray the Jewish state as a uniquely malignant force in the world. And double standard is lavishing criticism on Israel for things that other countries do without arousing significant opposition.

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, or BDS, is often criticized as anti-Semitic under two of these criteria. Because it calls for the return of Palestinian refugees to Israel, which if implemented would effectively overturn Israel’s Jewish character, the movement implicitly rejects Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state. And because it focuses on Israel alone (ignoring other countries that are also occupying disputed lands, for example), it runs afoul of the double standard criterion. Under President Donald Trump, the United States made this position official American policy in 2020 when he labeled the boycott movement anti-Semitic.

The Anti-Defamation League has offered a slightly different test. According to the ADL, criticism of Israel becomes anti-Semitic when it holds all Jews responsible for Israeli actions, denies Israel the right to exist, or employs classic anti-Semitic imagery or ideas. The ADL considers the BDS movement’s goals to be anti-Semitic, particualrly its denial of Jewish self-determination, along with faulting it for making traditional expressions of anti-Semitism more likely or politically palatable.

The idea that fierce criticism of Israel, and even denial of its right to exist in its current form, is anti-Semitic is highly contested. Among the most common arguments made by critics of this linkage is that many Jews themselves oppose the existence of Israel — most noticeably, though by no means exclusively, the various Hasidic groups that believe it is heretical to establish Jewish sovereignty in the holy land prior to the coming of the messiah.

Ilan Pappe, an Israeli-born historian, has called the idea that anti-Zionism is anti-Semitic “outrageous and ridiculous” and charged that it is used as a tool to stifle debate and criticism of Israel. Proponents of BDS insist the movement is not anti-Semitic, saying it peacefully opposes Israel for what it does, not what it is, and that its many Jewish supporters belie the notion that it’s rooted in anti-Jewish animus.

“We reject the assertion that BDS is inherently anti-Semitic and defend activists who employ the full range of BDS tactics when they are demonized or wrongly accused of anti-Semitism,” the anti-Zionist group Jewish Voice for Peace says on its website. “We believe BDS is a meaningful alternative to passivity engendered by two decades of failed peace talks, and is the most effective grassroots means for applying nonviolent pressure to change Israeli policies.”

Most mainstream Jewish organizations reject these arguments, holding that anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism are practical equivalents — if not theoretical ones. And in recent years, they have gotten substantial support from world governments from this position.

The most significant endorsement was the adoption in 2016 of a working definition of anti-Semitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, a 34-nation partnership committed to promoting Holocaust education and remembrance. While noting that “criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country” is not anti-Semitic, the IHRA definition included several examples of criticism of Israel that do qualify as anti-Semitic. Among them: Denying Jews the right to self-determination by claiming Israel is racist, holding all Jews responsible for Israeli actions, using classic anti-Semitic ideas to characterize Israel, and comparing Israel to the Nazis.