Unlike his grandfather Abraham, the first Jew, Jacob’s journey into the wider world is set into motion not by God’s urging to “go forth,” nor by dreams of a prosperous future: he just needs to escape. Jacob, like so many young people from his day up to ours, flees a home in which he is not safe. His brother intends to kill him, his divided parents are either unable or unwilling to protect him. At his mother’s urging, he leaves alone, seeking only the most basic of human needs: safety.

Twin sons of Rebecca and Isaac, Jacob and his brother Esau have been locked in conflict since the moment of their birth (Jacob was born grasping his brother’s heal). Jacob bargained Esau out of his birthright in exchange for a bowl of soup, and later, in the most fateful of scenes, followed Rebecca’s guidance in deceiving their blind, aging father by disguising himself as Esau and stealing the blessing that had been intended for his brother. Esau, learning of his brother’s cunning betrayal, begins to plan Jacob’s murder. What had been a tense difference between parents about which child to favor has erupted as a dangerous feud between their children.

Rebecca sends Jacob to her brother Laban, with hopes no higher than his refuge: “You will stay with him for a few days, until your brother’s rage has passed. Once your brother’s anger has passed and he has forgotten what you did to him—then I will send for you, and bring you back from there.” (Genesis 27:44-5)

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

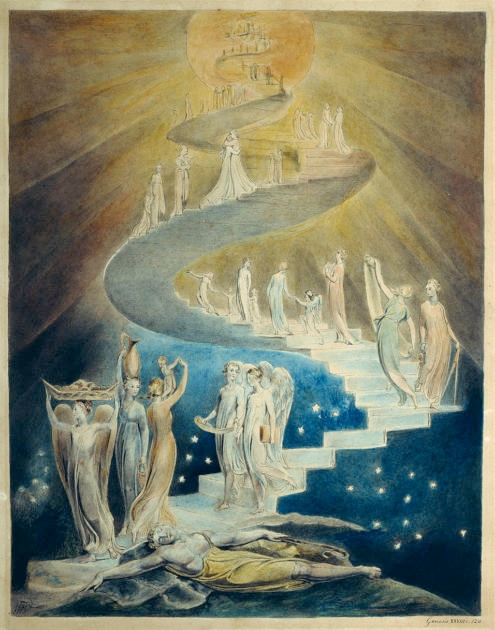

Jacob sets out alone. The first night of his journey, when Jacob rests his head on a rock, it is with the awareness that he has no one who can help him moving forward and no possibility of turning back. And it is at just this moment of isolation that Jacob meets God in his remarkable dream of angels ascending and descending: an experience that gives him hope, but no confidence.

Jacob finds a warm welcome at his uncle’s home and his stay with Laban extends well past a “few days” to over a decade (though the first seven years, when he worked for Laban for the right to marry Laban’s daughter, his beloved Rachel, felt like much less than that to him). But during those long years, Rebecca never sent for Jacob. Was this because the rage of his brother, Esau, had never softened? Neither we nor Jacob ever find out, though Jacob clearly suspected, or perhaps hoped, that this was the reason — likely more comforting than the notion that his mother had forgotten her promise call him home.

In these years — the formative ones of Jacob’s adult life, his equivalent of our 20’s and 30’s — the contours of his marriages and family must have been depressingly familiar. Having grown up in a home riven by parents who set their children against one another, Jacob finds himself now married to two sisters whose struggle for supremacy parallels Jacob’s own conflicts with his brother. (This may be because Rebecca and her brother, raised together, raise their own children in similar ways.)

And then, after twenty years, God appears to Jacob, saying “Return to the land of your fathers and your birthplace, and I will be with you.” (Genesis 31:3) It is hard to know what God’s sudden reemergence must have felt like to Jacob, but he seems to find in being beckoned home by God, rather than his mother, an opportunity to disrupt the patterns in which was raised, and which have dominated his life up to this point.

Rather than plotting his next steps himself, or approaching only one wife and thereby choosing between siblings — the modus operandi of his mother and her brother — Jacob calls both Rachel and Leah to join him in the field, a place where the three can together experience the possibility of distance from their parents’ homes. And as he tells them of God’s appearance, the sisters for the first time act together, answering in one voice: “Is there anything left for us in our father’s house? He treated us with no regard, selling us as things.” (Genesis 31:14-15) The three set off together in their uncertain, but for the first time hopeful journey.

What’s most poignant about Jacob is how neither he nor anyone else in his life finds what they longed for in youth. Leah never wins Jacob’s heart; Rachel, predeceasing Leah, never has Jacob to herself; and Jacob’s family will be divided against itself in ways that bring him confusion and grief for his entire life. And, even as Jacob and Esau’s encounter ends peacefully, the peace is a cold one: after their reunion, “Esau went back on his way, to Seir.” (Genesis 33:16)

Because of this, Jacob offers us a hopeful but cautionary picture of what may be possible for people who want their adult lives, not to mention the lives of their children, to be different from how they grew up. Completely remaking the families that raised us, much less the world we inhabit, is beyond our capacities. And yet we are not without agency; we are not destined to recreate the same lives and families that created us. More than that, it was precisely Jacob’s hurt at the hands of his parents that sensitized him to his wives’ suffering and gave him the resolve to stand against the ways their father had divided them. Perhaps this is how Jacob becomes the first father in human history whose sons, despite their divisions and fights, remain united as a family — the healer of the rift that opened between the very first brothers when Cain killed Abel.

Want to get to know more amazing, complicated, and relatable biblical personalities? Sign up for a special email series here.