Jewish sacred texts are traditionally interpreted in four ways summarized by the acronym pardes (Hebrew for “orchard”): p’shat, remez, drash and sod.

Midrash

The Bible is a complex and self-referential text. In the period of the classical midrash (rabbinic homiletical interpretation of Bible during the 2nd to 7th centuries), the sages wrote im (plural) to connect the various biblical texts to each other, to the life of sanctification prescribed by halachah (Jewish law), and to their own contemporary experiences. This midrashic approach was virtually the only way that Jews read the Bible until the Islamic conquest in the seventh century.

P’shat (Plain)

As Jews began to learn from Arabic scholars the principles of grammar and philology, a new model of Bible interpretation developed — the p’shat (plain) method. To its medieval practitioners, p’shat meant the search for the meaning of the text in its linguistic, literary, and historical context. Thanks to developments in Hebrew grammar, beginning with the research of Saadiah Gaon in the 10th century and continuing in Spain with rabbi-linguists such as Jonah Ibn Janach, the practitioners of the p’shat method had powerful tools to help them.

The p’shat method rejects the basic assumptions of the midrashic or d’rash (homiletical) method. Consider this verse reporting God’s words to Moses prior to the revelation on Mt. Sinai: “Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob, and tell the children of Israel” (Exodus 19:3). For Rashi, the pre-eminent biblical commentator who relied heavily on the d’rash method, the two halves of the verse must refer to different things. Rashi: “To the house of Jacob–these are the women, speak to them in a soft voice. And tell the children of Israel–explain the punishments and the details to the men.” Apologists might argue that Rashi implies that God instructs Moses to lay down the law with the naturally rebellious men, while the women don’t need threats, but however one understands Rashi, it is clear that Rashi is bringing a midrashic agenda to his reading of this verse.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

On the other hand, Avraham Ibn Ezra, of the medieval Spanish school, presents two different p’shat readings. The first is based on philological analysis; “To the house of Jacob–this refers to the those who are here today as well as their descendants…and the word house I have already explained” referring to his commentary on Exodus 1:1, where he shows that “house” means one’s descendants. He explicitly rejects the reading that “house” means wife, as Rashi had read it. Ibn Ezra’s second reading is literary:

“Why are [people making up] all of this? It is as if they haven’t read the prophets, who repeat themselves for emphasis, and this is the approach of clarity. We also see this in the [liturgical poetry of] the ancients in the prayers for Rosh Hashanah.”

Modern philological methods might differ from Ibn Ezra’s reading, but the literary analysis of parallelism accords exactly with how any modern scholar might read this text. Other great medieval practitioners of the p’shat method, like the Rashbam (a grandson of Rashi) explicitly assert their fidelity to the midrashic method for the sake of deriving law and for ethical instruction, but when it comes to interpreting scripture, they argue that one needs to use rational and scientific tools like the linguistic tools and knowledge of history. According to this approach, interestingly, the p’shat can disagree with the halacha (Jewish law).

Remez and Sod

Two other models of interpretation, although less widely applied, include remez (hint), which reads the biblical text as an allegory or extended metaphor, and sod (secret), which reads the Bible through the lens of Judaism’s mystical lore.

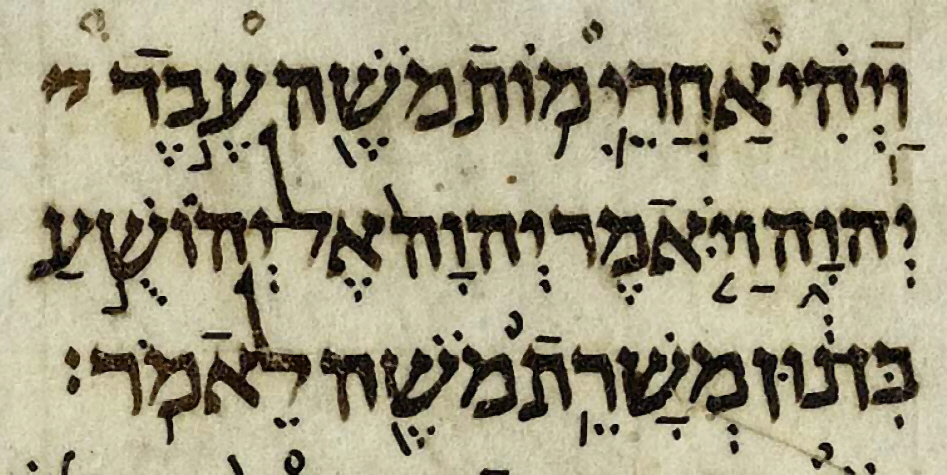

These four methods — p’shat, remez, d’rash and sod — have traditionally been referred to by an acronym combining their first letters PaRDeS (cognate with the English word paradise), which means orchard or garden. Each of these approaches has much to offer the modern reader of the Bible. Reading the Bible with the Mikra’ot Gedolot (Big Scriptures), which has a little biblical text on each page surrounded by lots of different traditional, mostly medieval, commentaries (including Rashi, Nahmanides, and Ibn Ezra) is like walking into an ancient conversation, a thoughtful debate conducted over the course of many centuries, locations, and cultures.

Modern Approaches

This thoughtful debate continues well beyond the Middle Ages, as Jews in the modern world create commentaries reflecting their own experiences and concerns. Some modern Jewish Bible scholars contend with the challenges raised by scientific study of Judaism, and biblical criticism. Others read the Bible with an eye towards advocating a particular kind of Jewish ideology. Whatever your perspective, the biblical text is open and your interpretation valued — join the conversation.