For Jews who wish to observe the rituals of their faith, wartime may pose seemingly insurmountable challenges. The exigencies of war can make the observance of the Sabbath, holy days, and rules very difficult. As the Arab attack on Israel during of 1973 made clear, Jewish soldiers must, on occasion, subordinate religious observance to combat. Despite the frequent priority of war over religion, there are times, such as the funeral of a fallen Jewish soldier or at the bedside of a wounded Jew, when religion can shape war policy.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Jews could not serve as chaplains in the U.S. armed forces. When the war commenced in 1861, Jews enlisted in both the Union and Confederate armies. The Northern Congress adopted a bill in July of 1861 that permitted each regiment’s commander, on a vote of his field officers, to appoint a regimental chaplain so long as he was “a regularly ordained minister of some Christian denomination.”

Only Representative Clement L. Vallandigham of Ohio, a non-Jew, protested that this clause discriminated against soldiers of the Jewish faith. Vallandigham argued that the Jewish population of the United States, “whose adherents are . . . good citizens and as true patriots as any in this country,” deserved to have rabbis minister to Jewish soldiers. Vallandigham thought the law, which endorsed Christianity as the official religion of the United States, was blatantly unconstitutional. However, there was no organized national Jewish protest to support Vallandigham and the bill sailed through Congress.

Three months later, a YMCA worker visiting the field camp of a Pennsylvania regiment known as “Cameron’s Dragoons” discovered to his horror that the officers had elected a Jew, Michael Allen, as regimental chaplain. While not an ordained rabbi, Allen was fluent in the Portuguese minhag (ritual) and taught at the Philadelphia Hebrew Education Society. As Allen was neither a Christian nor an ordained minister, the YMCA representative filed a formal complaint with the Army. Obeying the recently enacted law, the Army forced Allen to resign his post.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Hoping to create a test case based strictly on a chaplain’s religion and not his lack of ordination, Colonel Max Friedman and the officers of the Cameron’s Dragoons then elected an ordained rabbi, the Reverend Arnold Fischel of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, to serve as regimental chaplain-designate. When Fischel, a Dutch immigrant, applied for certification as chaplain, the Secretary of War, none other than Simon Cameron, for whom the Dragoons were named, complied with the law and rejected Fischel’s application.

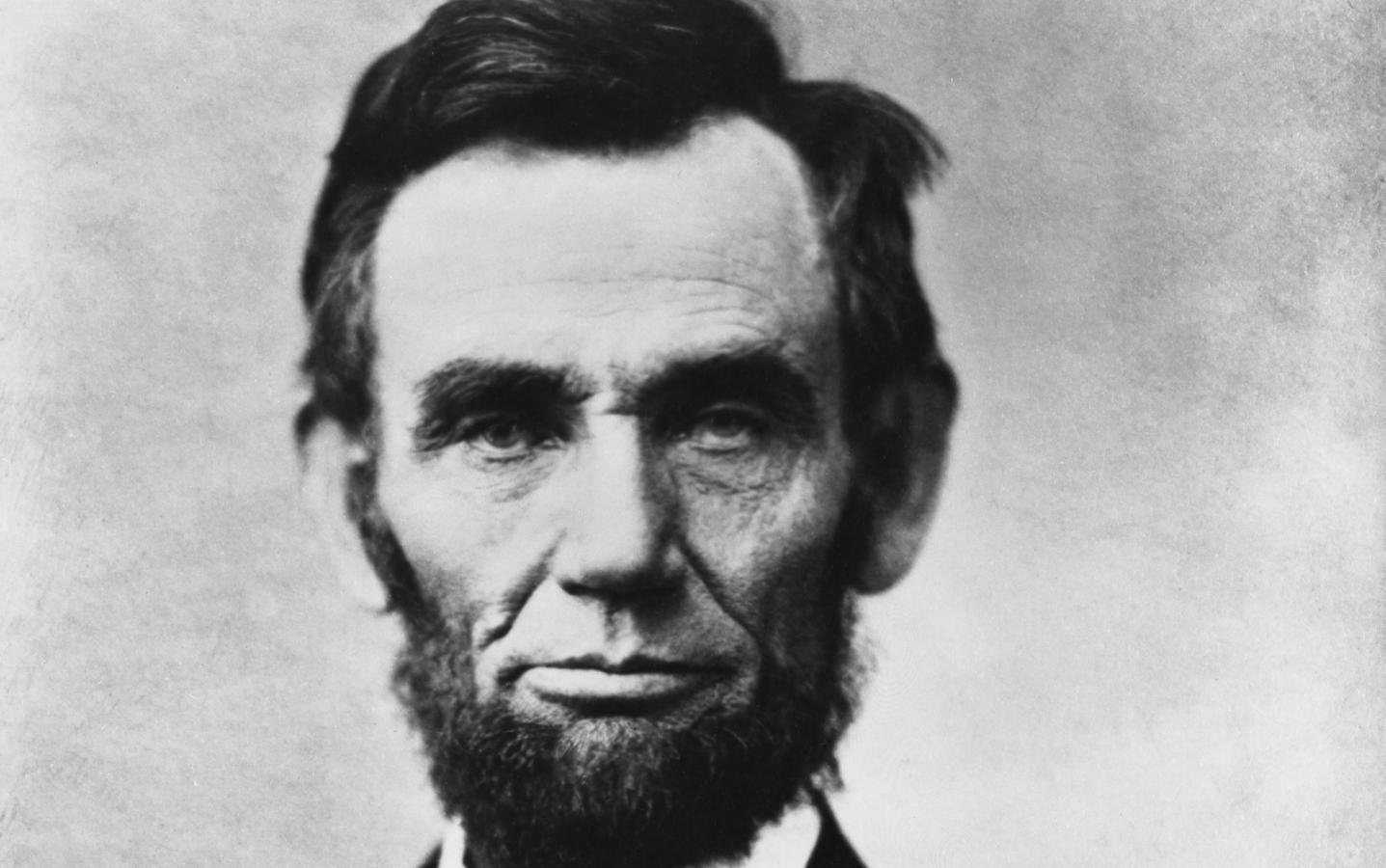

Fischel’s rejection stimulated American Jewry to action. The American Jewish press let its readership know that Congress had limited the chaplaincy to those who were Christians and argued for equal treatment for Judaism before the law. This initiative by the Jewish press irritated a handful of Christian organizations, including the YMCA, which resolved to lobby Congress against the appointment of Jewish chaplains. To counter their efforts, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites, one of the earliest Jewish communal defense agencies, recruited Reverend Fischel to live in Washington, minister to wounded Jewish soldiers in that city’s military hospitals, and lobby President Abraham Lincoln to reverse the chaplaincy law. Although today several national Jewish organizations employ representatives to make their voices heard in Washington, Fischel’s mission was the first such undertaking of this type.

Armed with letters of introduction from Jewish and non-Jewish political leaders, Fischel met on December 11, 1861, with President Lincoln to press the case for Jewish chaplains. Fischel explained to Lincoln that, unlike many others who were waiting to see the president that day, he came not to seek political office, but to “contend for the principle of religious liberty, for the constitutional rights of the Jewish community, and for the welfare of the Jewish volunteers.” According to Fischel, Lincoln asked questions about the chaplaincy issues, “fully admitted the justice of my remarks . . . and agreed that something ought to be done to meet this case.” Lincoln promised Fischel that he would submit a new law to Congress “broad enough to cover what is desired by you in behalf of the Israelites.”

Lincoln kept his word, and seven months later, on July 17, 1862, Congress finally adopted Lincoln’s proposed amendments to the chaplaincy law to allow “the appointment of brigade chaplains of the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish religions.” In historian Bertram Korn’s opinion, Fischel’s “patience and persistence, his unselfishness and consecration … won for American Jewry the first major victory of a specifically Jewish nature . . . on a matter touching the Federal government.” Korn concluded, “Because there were Jews in the land who cherished the equality granted them in the Constitution, the practice of that equality was assured, not only for Jews, but for all minority religious groups.”

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.