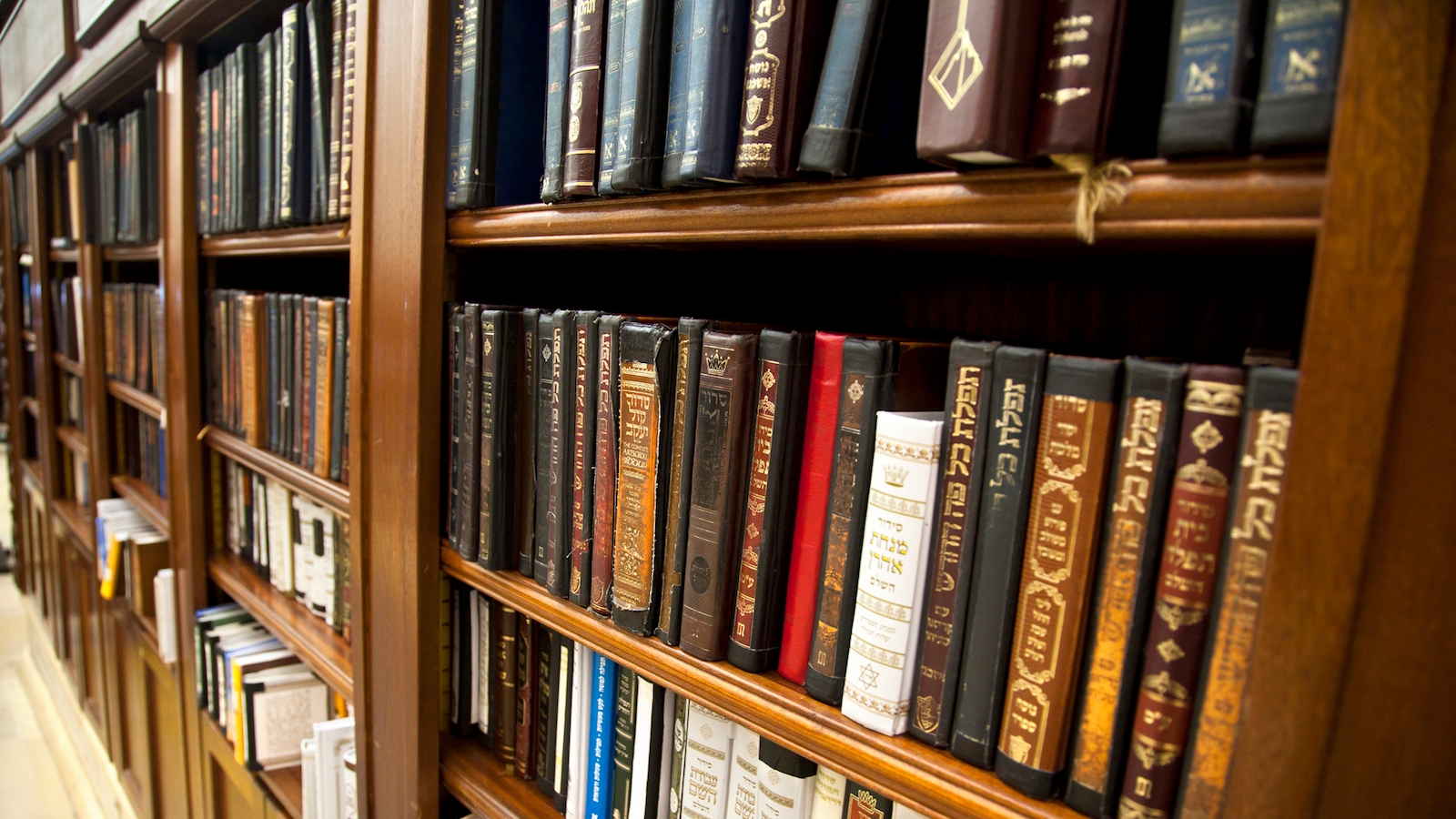

The wide range of philosophical and theological writings that analyze Judaism from a conceptual point of view account for what we call Jewish thought. As such, Jewish thought is not a single continuous tradition, but rather a varied mix of works, which reflect the specific ideological and historical positions of those who wrote them.

As scholars have often noted, the systematic analysis of ideas is foreign to biblical and rabbinic Judaism. Theological ideas can be deduced from the Bible, but they are rarely stated explicitly and unambiguously. Even monotheism, perhaps the most significant of all Jewish theological claims, is not clear-cut in the Bible. Many scholars believe that the biblical worldview reflects, in many places, a perspective that is fundamentally monolatrous (that is, it endorses allegiance to one specific God among many) rather than monotheistic.

Some later biblical books–Job, Ecclesiastes, Proverbs–which are categorized as Wisdom Literature, because of the advice and insight they give about daily living, do deal more explicitly with intellectual and conceptual themes. But even in these books, the ideas are–more often than not–imparted in an anecdotal or aphoristic way, not through reason and argumentation.

The Middle Ages was the golden era of Jewish philosophy. In Spain, Jewish thinkers embraced the rational thought of the classical Greek philosophers and began to systematically analyze the Jewish religion. Thinkers such as Saadiah Gaon and Maimonides tried to reconcile the claims of reason and revelation.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Though Jewish mysticism dates to the beginning of the first millennium, if not earlier, it was in the Middle Ages that it truly became a force in the development of Jewish theology. The kabbalists, as the medieval Jewish mystics came to be known, developed intricate theories about the nature of God and the world.

Because of Jewish mysticism’s non-rational bent and its interest in disciplines such as magic and demonology, traditional scholarship has tended to see it as distinct from and antithetical to Jewish philosophy. However, some recent scholars have questioned this distinction, as many mystics were influenced by philosophy and many philosophers had mystical inclinations.

The Enlightenment ushered in an increasingly secular age, and Western philosophy drifted away from traditional religious ideas. In response, modern Jewish thinkers articulated worldviews that integrated Judaism with this new secular reality.

Trends in non-Jewish thinking have always influenced Jewish thought. Medieval philosophers plundered classical Greek sources and studied their Muslim contemporaries. In the modern era, this interaction between Jewish and non-Jewish thought continued, as many general philosophical trends spawned Jewish counterparts. Moses Mendelssohn interpreted Judaism in terms of rational Enlightenment ideas; Hermann Cohen conceived of Judaism in neo-Kantian terms; Martin Buber developed a Jewish existentialism.

Though most figures usually included in the canon of modern Jewish thought are associated with liberal Judaism, traditional Jews have also produced theological works. Some, like the Orthodox theologian Joseph Soloveitchik, drew on non-Jewish thinkers, such as Søren Kierkegaard, while others rely only on explicitly Jewish sources.

A clear definition of Jewish thought has been tested in modern times by thinkers who are Jewish, but whose work isn’t concerned with explicating Judaism, as well as thinkers who split their time between general thought and Jewish thought. Were Karl Marx, the father of communism, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher of language–both of whom were of Jewish heritage–Jewish thinkers? Are all of Hermann Cohen’s works, even his commentaries on Immanuel Kant, “Jewish”?

The contemporary French philosopher Jacques Derrida represents an interesting recent example of these uncertainties. Derrida, whose philosophy of deconstruction is one of the most influential intellectual movements of our time, has rarely written on explicitly Jewish themes and sources. However, the question of his “Jewishness” has generated great debate, resulting in symposia, articles, and at least one book, Gideon Ofrat’s, The Jewish Derrida.