Ahhh, the ’90s. It was an era when people started using something called “e-mail” to communicate with each other, scientists cloned a sheep named Dolly, and then-President Bill Clinton became embroiled in a sex scandal (with a young Jewish woman). All of which was fodder for the nation’s comedians at the time. But what were some of the more overtly Jewish themes, topics, and trends that were put under comedic scrutiny by Jewish comics of the 1990s?

Seinfeld

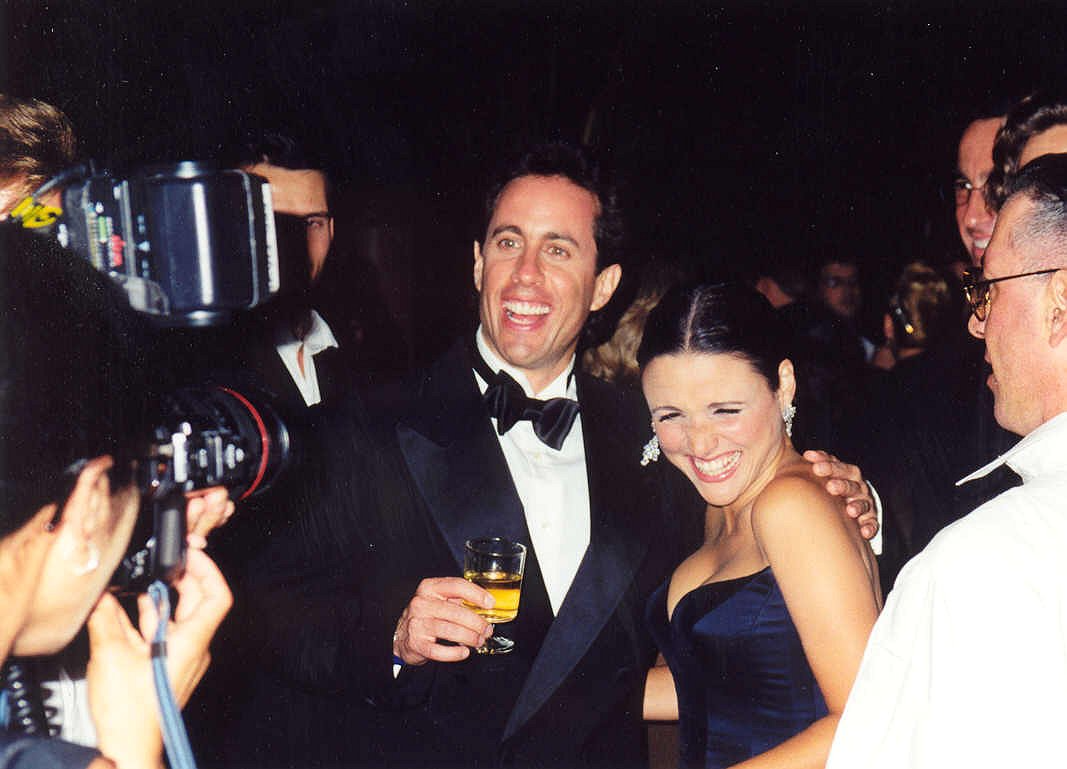

Observational comedy — that is, comedic observations based on everyday life — was a defining characteristic of American comedy in the ’90s. The master of the form, Jerry Seinfeld, was also the single comedian most associated with Judaism during that decade. His TV sitcom Seinfeld (1990-98) was a forum for witty observation of life’s minutiae, and Jewish characters, Jewish food, and Jewish religious practices consistently served as inspiration.

Whether it was tricking Jerry’s kosher-observant girlfriend into eating lobster, kidnapping a baby rather than see the wee one undergo a circumcision, or Jerry fearing that his dentist has converted to Judaism simply so that he can make Jewish jokes with impunity, the show was a veritable Jewtopia of Semitic humor. Jerry Seinfeld seemed at times to be channeling some of his Jewish comedic predecessors, most notably Jack Benny. Like Benny, Seinfeld cultivated the image of a lone sane person surrounded by crazies, and like Benny, he often winked at the audience. (Seinfeld’s co-creator Larry David would continue mining Semitic humor in the following decade, with his HBO hit Curb Your Enthusiasm.)

Slapstick and Reverence

With an emphasis on multiculturalism and diversity, 1990s American culture allowed ethnic comedians of all stripes to openly discuss their respective cultures. African-American comedians such as Chris Rock, Asian-American comedians like Margaret Cho, and Jewish comedians like Jerry Seinfeld fearlessly aired their culture’s “dirty laundry.” But if Jerry Seinfeld mined ritual observances for their comedic value, the era’s Jewish enfant terrible, Adam Sandler, took a different tack.

Sandler’s characters (such as Opera Man or Canteen Boy) didn’t have their root in the absurdities of everyday life–they were larger-than-life buffoons. He presented himself as a sort of “Jerry Lewis 2.0,” a slapstick clown in a beanpole body. Sandler’s ordinary stand-up routine (free of Jewish references) was reliant on poop jokes and overt sexual references. But when he ventured into the realm of Jewish humor, he suddenly morphed into a Nice Jewish Boy. For proof, look no further than Sandler’s “ Song.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

“The Hanukkah Song” was first performed by Sandler in 1994 on Saturday Night Live. The introductory verse contains the heartfelt line, “If you feel like the only kid in town without a Christmas tree/Here’s a list of folks who are Jewish, just like you and me.” The song is a straightforward run-down of many well-known celebrities who are Jewish. For example: “Paul Newman’s half-Jewish/Goldie Hawn’s half too/Put ’em both together, what a fine-looking Jew!” Though seemingly irrelevant, the song has become a poignant anthem of Jewish pride. Sandler has spoken publicly about his childhood in New Hampshire and about the anti-Semitic taunts he endured as the only Jewish student in his public school. Perhaps this is what drove him to write the song.

Jewish Women Laughing

In the ’90s, it became more common to see female performers in comedy clubs and playing openly Jewish characters on TV and films. Among the pioneers were Susie Essman (who’s had supporting roles in such films as Keeping the Faith and Bolt) and Judy Gold (who was a writer/producer on the Rosie O’Donnell Show and who had a recurring role on the Drew Carey Show). While some might be put off by Susie Greene, the foul-mouthed character Essman essays on HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, she’s a strong-willed character, and a far cry from the typical “materialistic Jewish princess” stereotype so dominant in the ’80s. And half of Judy Gold’s routine seems to center around her mother, a lovable that many Jewish audiences can relate to.

Then there’s Sarah Silverman, whose stand-up act frequently references her Jewish identity. At one stand-up comedy show in the mid-’90s, Silverman came onstage with fellow Jewish comedian Sam Seder. She was dressed as Seder’s teenage nephew, a boy who complains: “My friends don’t even know who you are! Adam Sandler is funny, and you are not funny! I wish that Adam Sandler was my uncle! You suck, and Adam Sandler rocks!”

A Decade to Remember

Yes, Adam Sandler does rock. Like Jerry Seinfeld, Adam Sandler represented a completely new breed of emerging comedy: the openly-Jewish comedy rock star whose most famous routines were often about Judaism. What made both Seinfeld and Sandler so refreshing to young audiences is that they blended the old and the new. Just as Sandler fused the goony antics of Jerry Lewis with a more polished frat-boy swagger–nerdy, yet cool–Seinfeld’s persona was a more modern spin on an older template: Jack Benny in sneakers.

This was the essence of Jewish humor in the ’90s: Jewish humorists retrofitting the very idea of what it meant to be Jewish–and to play a Jewish character–in the last decade of the 20th century.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.